Pre-K Teachers Are Stressed and Say They Want to Quit

A recent survey shows that pre-K teachers are overworked, underpaid and contemplating leaving their jobs.

By Bryce Covert | June 16, 2025During the 2023-24 school year, a higher share of children were enrolled in preschool than ever before, and states spent record amounts of money on these programs. But a recent survey of public pre-K teachers could spell potential problems for states that want to keep expanding preschool programs.

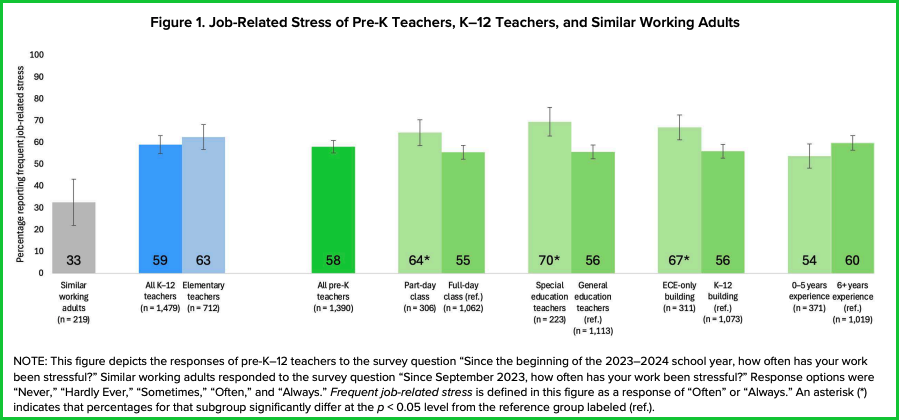

In a RAND survey of 1,427 pre-K teachers who work in public schools across the country, conducted in March and April 2024, respondents reported experiencing work-based stress at nearly twice the rate of comparable working adults in other kinds of jobs — those of prime working age with bachelor’s degrees who put in at least 35 hours a week. “Teachers of public school-based pre-K were generally more stressed,” noted Elizabeth Steiner, senior policy researcher at RAND and a lead author on the report. Two top stressors the teachers mentioned were dealing with student behavior and addressing students’ mental health.

Another top stressor they named was low compensation. And indeed, the survey found that pre-K teachers earned nearly $7,000 less, on average, than teachers in K-12 positions and $24,000 less than similar adults in other kinds of jobs. Steiner said that finding was “a little more surprising” given that the school-based pre-K teachers in their sample had similar educational backgrounds as K-12 teachers. But teachers overall face long-standing wage gaps with other fields. According to the Economic Policy Institute, the difference in pay, adjusted for factors like education and work history, hit a record 26.6% in 2023.

Pre-K teachers also reported working eight more hours, on average, each week than they were contracted for. Perhaps it’s little surprise, then, that another top challenge they named was administrative work that fell outside of teaching.

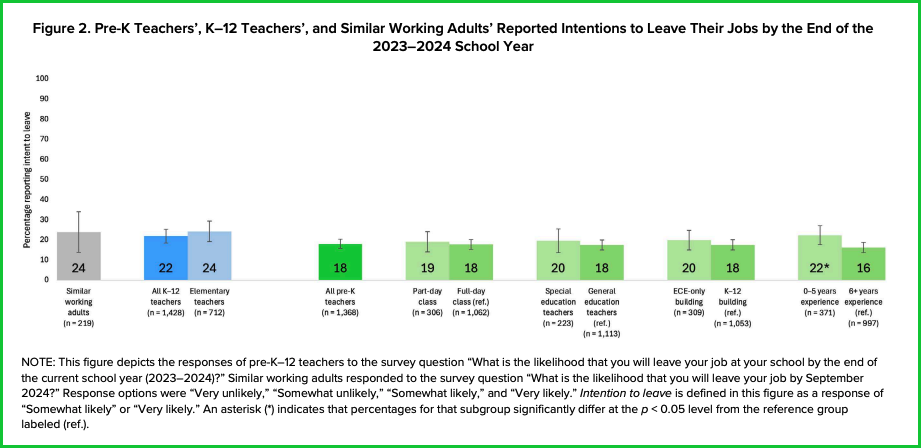

All of that stress while working for low pay seems to have pushed a lot of teachers to question their jobs. Nearly one in five survey respondents said that they intended to leave their jobs by the end of the 2023-24 school year. That’s “commensurate,” Steiner said, with rates of other workers, but it could still signal trouble. While Steiner noted that not all teachers who say they’re going to quit actually follow through, she said “it’s a measure of teachers’ job satisfaction” and “an early marker of attrition.” Other data has found high actual turnover rates among early childhood teachers. In Virginia, 35% of teachers serving children from birth through 5 years old left between fall 2023 and fall 2024. In Louisiana, about 37% of early childhood educators working one school year are gone by the following one, according to a working paper published by Annenberg Institute.

And while the turnover rate for pre-K teachers may look similar to other occupations, it has a greater impact when they leave their jobs. “Teachers gain a lot of experience and skill the longer they’re in a position,” said Anna Shapiro, associate policy researcher at RAND and co-author of the survey, and there has been “a lot of research on the importance of having stable environments for children in particular.” Losing experienced teachers who have connected with children is highly disruptive. It “can have knock on effects on quality,” Shapiro said.

States considering expanding pre-K might wish to think carefully about how they’re supporting and thinking about retaining their newest teachers so that the negative impacts on students in the classroom environment can be mitigated.

Elizabeth Steiner, senior policy researcher at RAND

These troubling findings about how pre-K teachers feel about their work come at the same time that states are heavily investing in preschool. The National Institute for Early Education Research (NIEER)’s 2024 State of Preschool Yearbook reported that the share of 3- and 4-year-olds enrolled in preschool for the 2022-23 school year reached an all-time high of more than 1.6 million, and 35% of 4-year-olds now attend a program. States that have enacted new universal preschool programs helped to “push the nation to these record high percentages,” the report says. The enrollment highs came on the back of record funding: States spent $11.73 billion on preschool in 2022-23, an all-time high.

There are plenty of challenges to continuing to expand preschool enrollment if states want to make further progress. One is finding physical space for new students; another is developing quality curriculum and standards. But “the biggest expense is teachers,” Shapiro said, and “one of the biggest barriers. You can only have so many children enrolled if you have a limited number of teachers.”

A particularly troubling trend that emerged in the RAND survey, then, is that teachers with five or fewer years of experience were more likely to say they intended to leave their jobs than those with more years under their belts. States that want to expand are going to need to recruit more new teachers and hold onto them. “Those numbers feel cautionary,” Steiner said. “States considering expanding pre-K might wish to think carefully about how they’re supporting and thinking about retaining their newest teachers so that the negative impacts on students in the classroom environment can be mitigated.”

“If you want to have a big staff pool, you need to have people who want to stay,” Shapiro added. “Well-being is really important in that retention.”

Shapiro noted that states will also have to contend with teacher pay gaps. The survey data suggests that “potentially for a teacher who has a similar level of experience and education that being a pre-K teacher is maybe less attractive than being a K-5 teacher,” she said. “It’s a very similar job but you’re getting paid less to do it.” That won’t just make it more difficult to recruit qualified and talented teachers, but to hold onto them once they gain more experience and keep them from seeking a better paying job in the K-12 setting. Tackling pay parity, then, is “an important policy step” to take to recruit more teachers, Shapiro said.

If you want to have a big staff pool, you need to have people who want to stay ... Well-being is really important in that retention.

Anna Shapiro, associate policy researcher at RAND

There may also be a temptation for states to expand part-day preschool programs, serving twice as many students with the same pot of money, given limited resources. But the survey data shows that could be a poor direction to take. Part-day pre-K teachers, who report the same number of work hours so are therefore likely saddled with teaching two different groups of children every day, reported higher levels of stress and intentions to leave in the survey than full-day teachers. “Our data does caution against attempting to do more with less,” Shapiro said.

The RAND findings are all the more troubling because, as Steiner noted, “public school-based pre-K teachers are just one piece of the overall pre-K landscape.” Teachers in other settings, such as center- or home-based child care programs, which cities and states sometimes include in their preschool systems, are likely to be faring even more poorly. “This sample of teachers is probably the ceiling,” Shapiro said. “We’re probably talking to the teachers that have the most resources in terms of pay and benefits.”

If states want to expand preschool enrollment, “part of a successful expansion would be supporting staff and ensuring that they are retained in their jobs to get the best benefits for students,” Steiner said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter