How to Expand Family Child Care in NC from CCR&R Team

Lessons from a team that helped 27 family child care programs get started in a year.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

State legislators from both parties want to expand family child care — the home-based sector of licensed child care, which has shrunk by more than a third since 2018. Both the House and Senate budget proposals include pilots to open new programs to meet the needs of families and employers.

For the past two years, a team from the nonprofit Southwestern Child Development Commission (SWCDC) has done just that, creating North Carolina’s first statewide system of support for family child care. In the past year, the organization has helped launch 27 new family child care programs, 20 of which are open, creating at least 160 new slots for children. Two are the first family child care programs in their counties.

Since September 2023, the team has awarded start-up grants to another 26 programs and business sustainability grants to 38 programs. It has created the first statewide family child care mentorship program, regional communities of practice, and a marketing campaign that has garnered interest from more than 200 prospective providers since April.

The funding to do this work — from a state legislative pilot in the 2023 budget and a state contract through the Child Care Development Fund (CCDF) — ends at the end of June.

As state leaders ask how to improve child care access and affordability, the project’s lessons should carry forward, said Daniel Bates, the statewide project’s manager.

“I just really felt like we’ve done something here, and I hope that, no matter what, it still continues, because family child care is so incredibly important,” Bates said. “And they are part of early childhood education.”

‘People that will be around for a while’

Expanding family child care takes one-on-one support for new providers who often bring a passion for children but little knowledge of the complex regulations and business challenges that come with starting and operating a program, the project leaders said. It also requires funding.

In 2024, SWCDC, a nonprofit focused on early care and education based in western North Carolina, was awarded $525,000 from the Division of Child Development and Early Education (DCDEE) from legislative pilot funding to expand access to family child care. The project’s expected output was to help 18 programs get started. Instead, it has helped launch 27 programs by awarding grants to cover start-up costs.

The grants ranged from $5,000 to $20,000 depending on the providers’ needs and the strategic goals of the project. The average grant was about $13,000.

Providers also spent their own money to open their programs outside of the grants. A survey of some of the providers found that most had spent between $1,000 and $5,000 before receiving grants to prepare their homes and buy materials.

The new providers are in 19 counties. In Alleghany and Montgomery counties, grant recipients will be the only family child care providers in their counties. Two providers speak Spanish fluently, according to the project leaders. At least 18 have college degrees. Four of the new providers were under 30 years old. Six were in their 30s; 10 were in their 40s.

“These are people that will be around for a while,” said Vickie Ansley, SWCDC’s Child Care Resource & Referral (CCR&R) regional programs manager and family child care in-home program activity coordinator.

That grant funding was layered onto a larger statewide family child care project the organization has been leading since February 2023 through a separate $3 million contract with DCDEE from the CCDF, the federal funding stream that helps states raise the quality of child care and helps working families afford it.

The statewide project had many components, including start-up grants of up to $10,000 and business grants of up to $5,000 for access to business training, software, or devices to manage programs. It provided 64 professional development workshops to providers on a range of issues. It also created a framework for family child care substitute pools and a database of zoning contacts and information.

Hands-on support from regional consultants

The crux of the project, however, was all about hands-on support and community building, the project leaders said. The project funded 17 family child care consultants who reached 477 providers in 73 counties with coaching and consultation.

The consultants, trained in the specifics of owning and operating a family child care program, were embedded in the 14 regional CCR&R hubs covering all 100 counties.

“We’re talking about people located in those communities,” Ansley said. “They know the (providers), or they know somebody who knows them.”

The PDG contract is in process but will be awarded to Acelero Charitable Foundation “in collaboration with multiple agencies that support family child care.” It will focus on increasing quality and family engagement, the spokesperson said.

DCDEE employs licensing consultants who meet with all types of potential child care owners to begin the licensure process. The licensing consultants began recommending reaching out to the regional family child care consultants to new providers.

The family child care consultants then could provide knowledge specific to family child care, dedicate time and energy to decipher the complexities of starting and sustaining a business, and offer support that was independent from regulatory oversight and compliance. Some of the consultants were former family child care providers themselves.

“Prior to that, if an agency had capacity, then they provided support,” Bates said. “The services were somewhat limited, whereas this was full 100% dedication for family child care.”

The regional consultants received business training to advise providers on budget planning, financial reports, marketing, and recruiting and retaining staff.

Kathleen Hoffler, a regional consultant at the Partnership for Children of Cumberland County who once owned a family child care home, described the role as her “dream job.”

Hoffler said she has helped providers take better care of their businesses, their children, and themselves. She encouraged providers to take time off and to reach out for help.

“If you’re having issues with enrollment, if you’re having issues with collecting payments from parents, if you’re having behavior issues with kids or you’re worried that one of your kids might need some developmental screening, and you don’t have anybody to talk that out with, it’s real easy to get discouraged and possibly decide it’s not for you and you’re going to close your program,” Hoffler said.

The family child care consultants connected providers to the pilot grant opportunities and helped them budget what they needed and how they should spend the funding.

Since the consultants were embedded in CCR&R agencies, they could connect providers with a variety of professional development opportunities and resources.

And they connected providers to mentors — seasoned family child care providers who provided a listening ear and advice on overcoming obstacles — and to communities of practice, regional teams that met to share ideas and support one another.

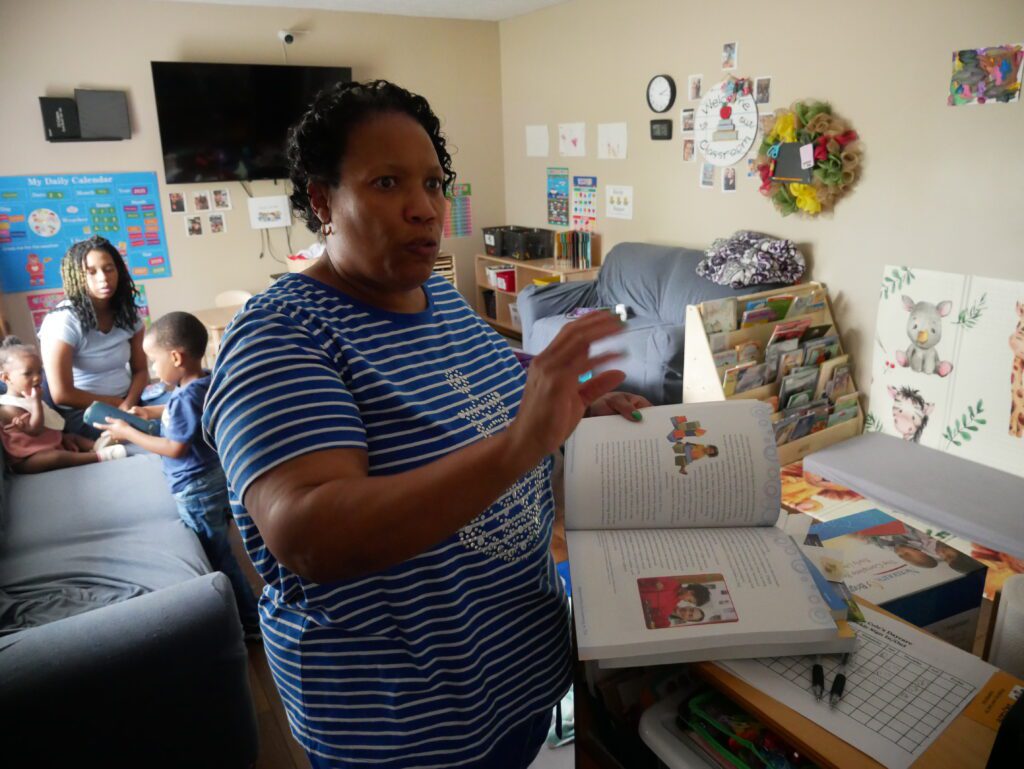

Annette Anderson-Samuels, owner of Phenomenal Kids Child Care Services, a family child care home in Kings Mountain, was one of those mentors. She said her advice to two new providers on how to advertise their programs kept them from closing. She recently helped a provider navigate a tough conversation with parents who were not following her policies.

“It’s to help each other become better at what we do as child care providers,” Anderson-Samuels said.

There were 22 mentors and 44 mentees across the state. In his decades working in early childhood, Bates said the group has been a standout.

“They’ve crossed county lines to go help each other in person,” he said. “The interest and the willingness, wanting to improve themselves, is really out there if they have the opportunity to do that.”

‘The lost segment of early childhood education’

The number of family child care programs, child care businesses within a residence, has fallen by about 36% since 2018, compared with an overall 15% decline in all types of licensed child care.

Eighty-five percent of licensed child care closures from February 2020 to June 2024 were home-based programs.

As a generation of providers age out of the work, a lack of awareness, funding, and support — along with increased regulation — has kept new providers from entering the field, project leaders said.

The team was intentional about listening to providers’ experiences and needs before developing a system of support.

Many brought up the low rates that family child care providers receive per child to participate in the state’s subsidy program. These rates, the state has found, do not cover the full cost of providing child care in any setting. Home-based programs receive lower amounts per child than centers. And providers in rural and low-income areas often receive lower rates than those in higher-income counties.

In rural areas where market rates are lower, “even though we need family child care in those communities desperately, market rates are a hindrance,” said Lori Jones-Ruff, SWCDC’s regional programs manager.

Jones-Ruff also sits on Gov. Josh Stein’s Task Force on Child Care and Early Education, where members have discussed the need for higher subsidy rates and a statewide floor rate that would level the playing field among counties. Research has shown the geographic disparities are wider than place-based differences in cost.

“That’s not just a center issue,” she said. “It’s for family child care as well.”

Low funding from public sources and private tuition leads to low compensation for family child care professionals. The median wage for home-based providers in 2023 was $10.20.

The team also heard about obstacles due to HOA rules and zoning regulations. They found that local ordinances were putting up barriers to new programs in some places. Septic tank requirements were among the most common and most expensive problems.

“(Providers) have recognized, ‘I don’t really need to run to Raleigh; some of the challenges I have are really just in my own backyard, and I just need to talk to my town or county,’” Bates said.

The team heard about the isolation many providers feel, being alone in their homes all day without a network to air ideas or lean on when challenges arise. Providers said they did not feel respected or supported by the state.

“Historically, there was a huge emphasis put on center-based care in North Carolina,” Jones-Ruff said. “Homes did not feel that they were as valued and as supported as center-based. And so there was a period of time where they really felt like they were kind of the lost segment of early childhood education in North Carolina.”

So the team built a strategy based on both funding and relationships.

‘Like a prayer answered’

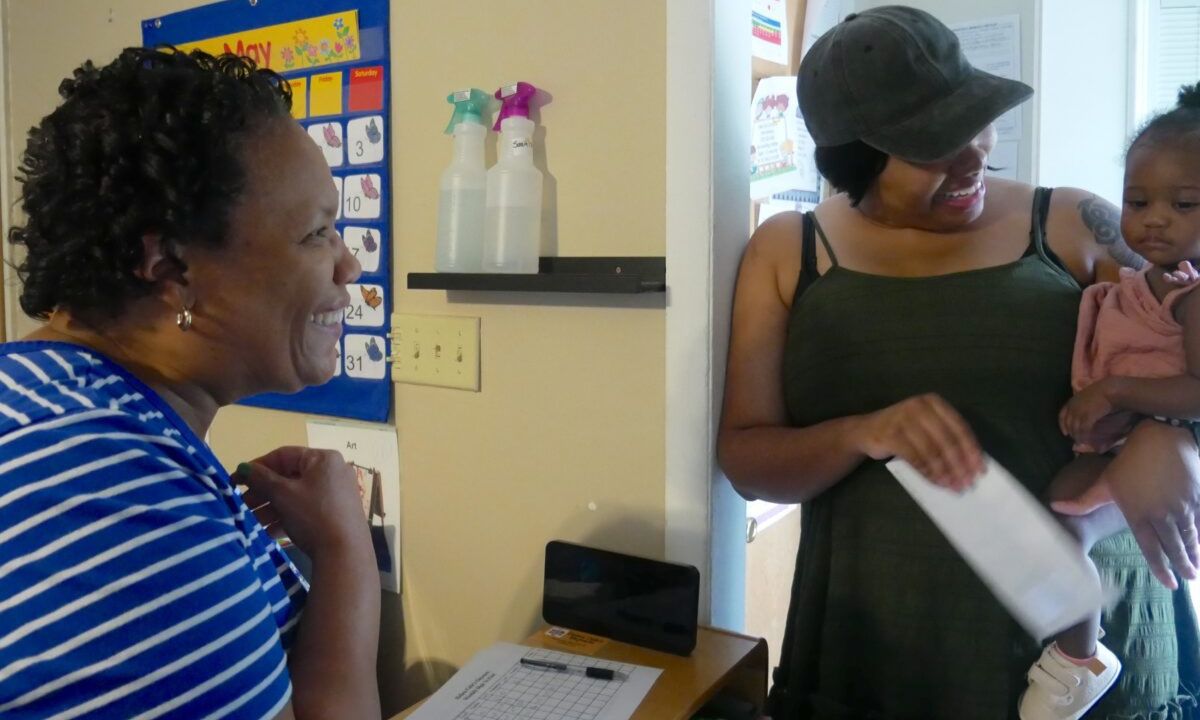

For Helen Cole, that assistance and funding was key to opening her family child care home in Taylortown in Moore County.

“I just feel like this wouldn’t have been possible without the support and the funds,” said Cole, who recently earned her four-star license to care for children from infancy to 12 years old at Helen Cole’s Day Care.

She received more than $17,000 to start her program from the legislative pilot funding. She bought new outside equipment, furniture, dramatic play sets, age-appropriate toys and books, a new kitchen faucet, a state-approved curriculum, and a new laptop.

Cole heard about the potential grant funding for start-up costs from the state licensing consultant. She was also connected with Hoffler.

Cole was excited to open after hearing about a local demand for second-shift care. After retiring as a substitute teacher in her local school district, she needed more income and was eager to fill a community need.

But after her initial meeting with a licensing consultant, she received a long checklist of everything she had to do. She said she felt overwhelmed.

“It was just so much information,” she said. “There are things on the website, but how do you adjust it for your day care?”

Plus, Cole had experience helping in her sister’s child care program, but she did not know the ins and outs of operating a small business. Even with a background in accounting, she knew the role would be challenging. So she reached out to Hoffler for an in-person meeting.

“It was like a prayer answered,” Cole said. “She broke it down for me.”

Hoffler helped Cole navigate the tough decisions that come with operating a business from your home, such as how much living space she was willing to sacrifice and what renovations were needed. And she helped Cole create a budget to apply for grant funding through the legislative pilot. She gave her ideas on high-quality and age-appropriate materials.

She also connected Cole with a mentor, helped her with business skills, and connected her with other resources through the Smart Start partnership.

Hoffler has helped her advertise her program and hold on through the ups and downs of enrollment, Cole said. Because she needed to hire another teacher, her niece Danielle Dixon, Cole said she is breaking even but has not started making a profit or been able to pay herself. She said she has been advised that it can take nine months to a year.

She said low subsidy rates and parents’ inability to afford her private rates have also been financially challenging. She serves one student whose parents are both working, making too much to qualify for a subsidy, but cannot afford her private rate of $200 per week. She only charges that family $85 per week.

Dixon, who has been working in child care professionally for 11 years but informally since she was 16 years old, has both of her children enrolled at the program. Dixon said her grandmother and mother, as well as three of her aunts, have worked in child care. She decided to partner with her aunt, Cole, to return to working with young children in a creative, exploratory environment after working in public schools.

Helen Cole’s Day Care opened in December in the home she was raised in, and where her mother used to take care of children whose parents were at risk of losing custody.

“All of our lives, we’ve had other children here,” Cole said.

Both Dixon and Hoffler have helped Cole strengthen her understanding and practice of early childhood care and education. Her program’s philosophy is based on relationships, exploration, and emotional and social development. Then academic foundations are added.

“It’s that give and take between you and this child,” Hoffler said. “They’re going to learn more from you if you are actively engaging with them and talking to them throughout the day, than they’ll ever learn if you give them a coloring sheet and try to teach them how to stay in the lines. There are no lines in early childhood.”

“That was a wow moment,” Cole said. “I understand that we have to have a curriculum, and we do, but the biggest thing is for them to develop on their own.”

It is this one-on-one attention and intimate environment that make family child care appeal to so many parents. Rural children, low-income children, and children of color are more likely to access home-based care than center-based, according to national advocacy and research group Home Grown. It is often more affordable, more convenient and flexible for nontraditional working hours, and more culturally and linguistically relevant to diverse families.

Kailyn Green, whose daughter has been at the program for a month, said she toured other programs with open spots but they “didn’t feel right.” Then she visited Cole’s program and did a walk-through.

“I was like, ‘I’m sold. I’m good,’” Green said.

A licensed clinical social worker, Green said she has been able to return to work without worrying. She receives texts and videos of her daughter’s days and has been impressed by how much she has progressed, especially with eating more consistently.

“I love that she truly gets the attention,” she said. “She’s been able to form a relationship with her. It’s been great.”

Hoffler said she was excited to hear about Cole’s recent accomplishment: earning four out of five stars on the state’s quality rating scale.

“I’m just so proud of her,” she said. “She handled it like a pro.”

What’s next?

There are multiple efforts to build different kinds of supports for family child care. DCDEE said the project with SWCDC taught them that “Family Child Care Homes (FCCHs) would benefit from additional funding, continued community engagement, and professional development to improve quality,” according to a DCDEE spokesperson.

“FCCHs are a vital part of our state’s early care and learning network, and DCDEE is committed to continuing our support for these small businesses,” the spokesperson said in an emailed statement.

Though the contract for the statewide project ends on June 30, the spokesperson said the division will continue using CCDF funds and federal funds from the Preschool Development Grant (PDG) Birth through Five to provide business technical assistance and other services to family child care programs.

The PDG contract is in process but will be awarded to Acelero Charitable Foundation “in collaboration with multiple agencies that support family child care.” It will focus on increasing quality and family engagement, the spokesperson said.

DCDEE is also contracting with Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute at UNC-Chapel Hill to provide evaluation and coordination of the PDG Elevate FCCH project, which will provide extra subsidy funding to family child care programs to increase wages for providers.

The House and Senate budget proposals direct DCDEE to use CCDF funds to expand family child care capacity. The House would allocate $7 million over two years for a pilot in three localities, and the Senate would allocate $6 million for a pilot in Alamance, Harnett, and Johnston counties. The funding would go to councils of governments in each of those counties to select a third-party vendor. Both proposals have specific requirements for the chosen vendor, including experience in establishing family child care homes in at least three other states and rural areas, experience in operating a substitute pool in another state, and technology that connects families with providers and includes billing and coaching functions.

Meanwhile, Jones-Ruff said SWCDC will continue supporting family child care by retaining a statewide team with organizational funding — and will seek outside funding to continue other aspects of the project. Some of the family child care consultants will continue their work through local CCR&R or Smart Start funding.

“I can see just the monumental amount of work and the progress that has happened in such a short amount of time,” she said. “We’re not going away.”

This article first appeared on EdNC and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)