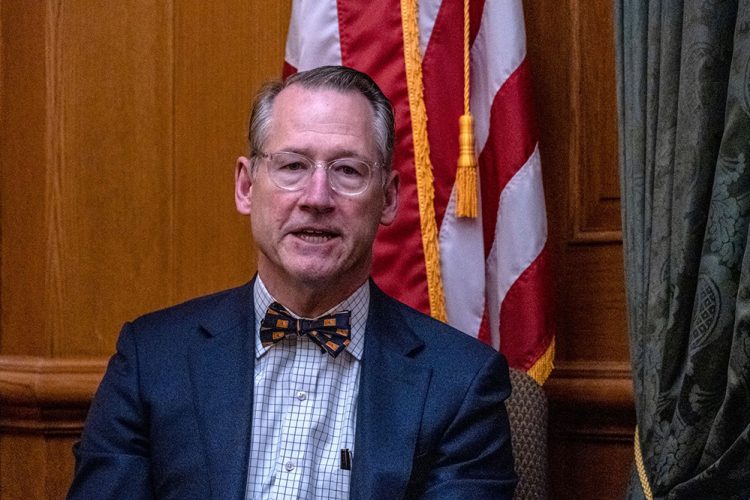

Tennessee state Sen. Bo Watson wants to eject undocumented children from classrooms. But first, he needs their data.

Under legislation proposed in February, students statewide could be required to submit birth certificates or other sensitive documents to secure their seats — one of several state efforts this year designed to challenge a decades-old Supreme Court precedent enshrining students’ right to a free public education regardless of their immigration status.

Watson, a Republican, argues undocumented students are a financial drain on Tennessee’s public schools even though state officials don’t know how many are enrolled there. He sees a way to find out.

“If someone is not able to produce their documentation then you would make the assumption that they are here illegally and it would allow you to begin to collect some data as to the number of students in a school system that are either undocumented or are here illegally,” Watson said in an interview with The 74. “So that’s sort of a starting point for us, in terms of trying to understand what the financial cost is.”

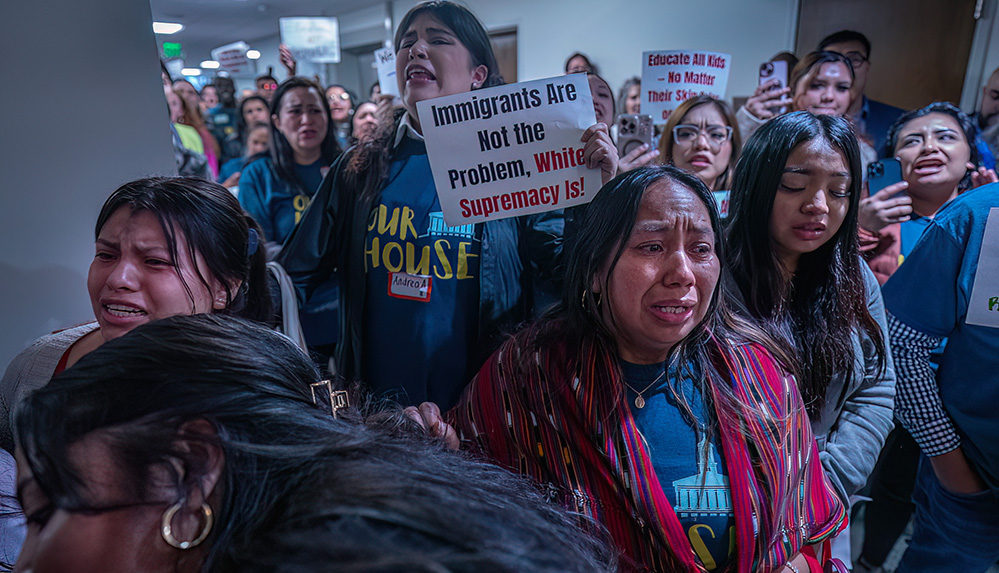

The controversial legislation, which has drawn protests and could jeopardize more than $1.1 billion in federal money for Tennessee schools, has also sparked alarm among privacy advocates who warn efforts to compile data on students’ immigration status could be used not just to deny them an education — it could also fall into the hands of Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

As the Trump administration ramps up deportation efforts and tech billionaire Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency reportedly works to create a “master database” of government records to zero in on migrants, civil rights advocates warn that education data about immigrant students, such as home addresses, could be weaponized.

“That would be an easy grab for federal officials,” said Cody Venzke, a senior policy counsel at the American Civil Liberties Union focused on surveillance, privacy and technology. “Schools are a geographically based governmental service and that makes that data particularly vulnerable.”

Sign-up for the School (in)Security newsletter.

Get the most critical news and information about students' rights, safety and well-being delivered straight to your inbox.

Republican lawmakers in Tennessee, Oklahoma and Idaho seek to compel educators to collect records about students’ immigration status that have traditionally been outside their purview. Meanwhile, reams of existing information about immigrant students — including their birth locations and how long they’ve lived in the U.S. — could serve as proxies to help authorities identify and track undocumented students or those with undocumented family members, said Elizabeth Laird, the director of equity in civic technology at the nonprofit Center for Democracy and Technology.

For Laird, a recent executive order signed by President Donald Trump to merge federal and state data, surveillance-driven immigration enforcement efforts and irregular data collection efforts across federal agencies set off alarm bells. Laird recently published a white paper on schools’ legal obligations to keep sensitive student data secure.

“What we’ve seen in the last three months is unprecedented access to and consolidation of data about people across a number of federal agencies, and that means taxpayers, it means student loan borrowers, it means Social Security recipients,” Laird said.

Immigration enforcement officials have already turned to data to deport international college students, unaccompanied minors who came to the U.S. without their parents and immigrant taxpayers whose IRS returns were once considered absolutely confidential. Additional irregular data collection efforts have been carried out across federal agencies in the name of rooting out fraud and waste.

“You don’t have to go very far to see the connection between the data environment that they’ve created in the name of fraud, waste and abuse and how it relates to immigration enforcement,” Laird said. As Republicans argue that immigrants are wrongly accessing benefits and causing financial turmoil in public schools, she said, “Immigration has become a fraud, waste and abuse issue.”

Officials at the White House and Education Department didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Data collection in the surveillance age

At just over 100 days into Trump’s second term, there is no evidence that K-12 students’ data have become a specific target for immigration enforcement, even after ICE scrapped a longstanding policy this year that restricted agents from carrying out raids at schools, churches and other “sensitive locations.”

Watson told The 74 his legislation is about ejecting undocumented children from public schools and not about removing them from the country altogether. But a recent Center for Democracy and Technology survey suggests that educators even pre-Trump were already sharing student information with immigration enforcement officials. Some 17% of teachers reported that their schools provided student grades, attendance and discipline information to immigration authorities last school year, the survey found, as well as information collected by digital surveillance tools on school-issued laptops.

A recent executive order seeks to make vast data collection a lot easier. With a stated purpose of promoting government efficiency, Trump signed an executive order in March to eliminate “information silos” between federal agencies that have historically existed to prevent the government from abusing its access to Americans’ sensitive personal information, including adoption records, citizenship information, IP addresses and student loan histories.

Under the order, a whistleblower claims the Trump administration is building a database of individual people unlike anything the U.S. government has had before — and one that’s been compared to the tactics of authoritarian regimes.

“Most breathtaking,” Venzke said, is the Trump administration’s efforts to gain unfettered access to information held at state agencies. Experts said the broadly defined order could apply to schools, state education agencies and third-party contractors.

The U.S. Department of Education generally doesn’t maintain large datasets of student data beyond financial aid records — which include students’ and family members’ Social Security Numbers and Individual Taxpayer Identification Numbers. Tax ID numbers are used by taxpayers without Social Security numbers to pay taxes regardless of their immigration status but could be leveraged as an indicator that someone is undocumented.

The real student data trove, however, resides at the state level. In fact, states have maintained data about foreign-born students for years and the threat of immigration enforcement is “not limited to undocumented students,” according to the CDT white paper. More than 1,400 international college students in the U.S. lost their visas in the first months of the Trump administration, although it recently reversed those revocations in the face of court challenges.

State education data is used to populate the U.S. Department of Education’s EdFacts initiative, which centralizes state-by-state information to guide policy development and includes information about students who were born outside the U.S. and have been enrolled in U.S. schools for less than three years. Though the data states provide to the federal government is aggregated, Laird warned that local education agencies could be compelled to share the underlying records that identify specific students.

Schools also identify immigrant children and English learners in order to receive federal grants that support their learning. Additionally, under the federal Every Student Succeeds Act, which requires students nationwide to take standardized tests, immigrant students who have lived in the U.S. for less than a year can opt out of the English assessments — waivers the CDT noted “can only be provided if schools know who these students are.”

Students cautioned against speaking out

Despite the recent executive order’s stated goal of preventing fraud, Laird said the mandate mirrors a 2019 executive order, issued during Trump’s first term, which sought to consolidate data for the explicit purpose of streamlining immigration enforcement. At least four states — South Dakota, South Carolina, Iowa and Nebraska — agreed to share driver’s license data with the Trump administration as it sought to pinpoint the citizenship statuses of every adult residing in the U.S.

“We’re in a time when the government is asking for things that they’ve never asked for before. So I’m really not sure what might happen if the government went to a state and said, ‘Give us your entire database with every piece of information about every student in public schools.’ ”

Julia Sugarman, associate director Migration Policy Institute

Julie Sugarman, associate director for K-12 education research at the nonprofit Migration Policy Institute said educators nationwide have taken steps to ensure students’ records aren’t used beyond their intended purposes, including for immigration enforcement. But the Trump administration’s vast data collection efforts present an unprecedented situation.

“States generally would have a full spreadsheet that includes identifying information, so yeah, if the government was to go to states and ask for that, that would set off huge alarm bells,” Sugarman said.

“We’re in a time when the government is asking for things that they’ve never asked for before,” she continued. “So I’m really not sure what might happen if the government went to a state and said, ‘Give us your entire database with every piece of information about every student in public schools.’ “

Digital surveillance tools being used by federal immigration officials to track down deportation targets — including social media monitoring software — have become widespread in K-12 schools. Digital surveillance tools, which track students’ online communications and web searches, could offer valuable data to immigration officials, Laird said. In some instances, students’ digital communications are automatically shared with local law enforcement officers who, in communities nationwide, have been increasingly deputized to help enforce federal immigration laws.

Social media surveillance tools used by K-12 schools and university educators have previously been leveraged to surveil student protests.

In the last few months, some K-12 students have already been warned to be careful about what they post on the internet as the government moved to revoked the visas of foreign-born college students for their participation in protests, social media posts and writing for college newspapers.

Martin Milne, president of the Connecticut-based Assist Scholars, said his organization has told international K-12 students that their ability to learn in the U.S. is conditional — and can be eliminated at a moment’s notice. The nonprofit scholarship organization currently helps nearly 200 international students enroll in U.S. private secondary schools.

“We’ve sent a really general reminder to students applying for visas to be particularly mindful that obtaining a student visa is really a privilege and it’s not a right and it comes with important responsibilities,” Milne said, echoing language recently used by the Trump administration. “And that if they abide by the responsibilities that come with being a visa holder, they’re not going to draw attention to themselves.”

Tennessee wants Trump’s permission

Back in Tennessee, a Republican-led effort to collect data about undocumented students and bar their access to public schools has stalled. Despite claims that immigrant students are a drain on school resources, a state audit warned the move could cost Tennessee as much as $1.1 billion in federal education money if officials fail to comply with federal laws that prohibit discrimination based on race or national origin.

Still, the climate caused by the legislative effort and Trump’s deportation efforts has students on edge, Kyle Carrasco, a high school government and economics teacher in Chattanooga, told The 74. Although his school doesn’t ask students about their immigration status, Carrasco said he suspects at least some are undocumented and several have already had family members taken into ICE custody.

“At the end of the day, immigrants regardless of documentation status are paying taxes, they’re paying into the system that they — if these bills become law — will be withheld from,” Carrasco said. “So I don’t necessarily understand the reasoning and the logistics beyond why we need to be identifying and tracking these students.”

Watson, the state senator, hasn’t given up, telling The 74 he hopes his bill will resurface after local officials receive assurance they won’t be penalized by the federal government. In an April 21 letter to the U.S. Department of Education, state Fiscal Review Executive Director Bojan Savic asked if Tennessee risked losing federal money for its failure to comply with civil rights laws.

With Trump in charge, Watson said he didn’t think the letter was necessary.

“This bill, were it to be enacted into law, would align with the strategies that the current administration is exercising,” Watson said, “and it would not put our federal dollars in jeopardy.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter