A Way Out of SCOTUS Charter School Ruling Mess: Focus on Mission, Not Religion

Kahlenberg: Changing laws to require charters to teach American democratic values would weed out parochial schools — and some secular ones as well.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

On April 30, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in a case that could compel states with charter school laws to authorize religious charters. Reporters from the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Wall Street Journal and The 74 said the court’s conservative majority bloc appeared “open to” religious charter schools.

Such a ruling would be bad for the country and deeply disruptive. It could upend the charter school sector, raising questions about the constitutionality of the federal charter school law and the laws in 47 states, all of which require charters to be nonsectarian. It could lead to blue states cutting back on charter schools and red states seeing a flood of religious charters open up, which would further balkanize an already divided country.

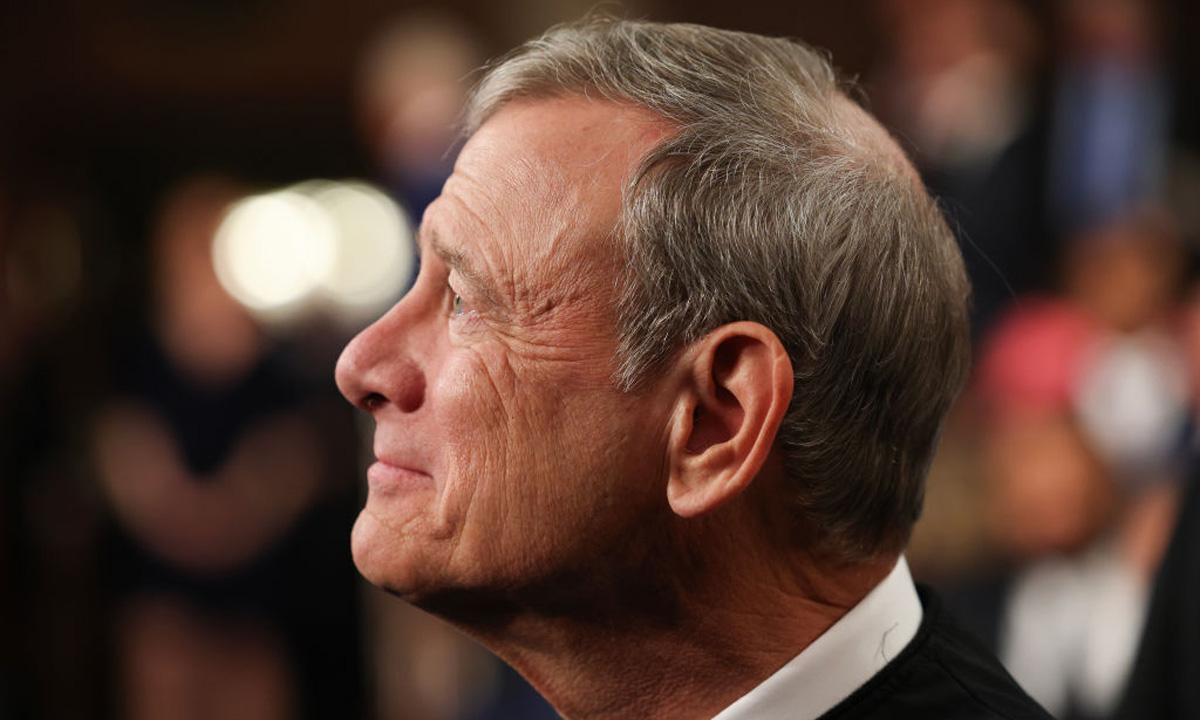

Is there any hope? The best outcome would be if one of the conservative justices — most likely Chief Justice John Roberts — ended up siding with the liberal justices and rejecting a requirement that authorizers must permit religious charter schools. The second-best outcome would be if policymakers took creative steps (as I outline below) to comply with an adverse Supreme Court ruling while preserving social cohesion and retaining for charter schools the flexibility they need to flourish.

I have a modest hope that Roberts’s vote may be in play. If he votes with the court’s three liberal justices, a 4-4 decision would let stand the Oklahoma Supreme Court’s decision opposing religious charters. (Justice Amy Coney Barrett is recused in the case.)

In the oral arguments, the justices homed in on the central question in the case: Are charters public or private? If they are public, then the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment prohibits them from being religious. If they are private, by contrast, the court’s interpretations of the First Amendment’s Free Exercise Clause that government cannot discriminate against religious schools would apply.

Roberts asked tough questions of both sides, but the most hopeful moment came when he noted that the state has “a much more comprehensive involvement” in charter schools than in private schools, which could tilt his thinking against religious charters.

Greg Garre, who served as solicitor general under former President George W. Bush, made a powerful case that charter schools are public. He noted that private schools differ from charter schools in eight respects:

- “Private schools can open without any state approval.”

- “There are no requirements or supervision of curriculum for private schools.”

- Private schools “can charge tuition.”

- Private schools “can restrict admissions.”

- Private schools are “not subject to general state assessment tests.”

- Private schools are “not subject to nearly the reporting requirements or oversight as public schools”

- Private schools “not subject to state rules regarding student discipline, civil rights [and] health”

- “There’s no process for closing” private schools “short of consumer fraud.”

If Roberts nevertheless decides, along with other conservatives, that charter schools are private schools, and states are compelled to authorize religious charters, that would set off a number of consequences.

First, blue states are likely to rebel. As Justice Neil Gorsuch noted, some states may begin “imposing more requirements on charter schools,” essentially making them more “public.” For a sector that thrives on independence, this could constitute a “boomerang effect.”

Second, red states are likely to see a number of religious private schools convert to charter status. As Justice Elena Kagan noted, “There’s a big incentive to operating charter schools, since everything is funded for you.” She expected to see “a line out the door” of applicants.

Third, there is likely to be more litigation. As the justices asked in the oral argument: If charters are deemed private schools, then does that mean a conservative Christian charter school could, as a matter of religious liberty, bar the admissions of Jewish, Muslim and gay students? Could the same school discriminate against gay or non-Christian faculty members? Could it reject state standards requiring that it teach evolution?

I found this all very depressing, but there was one compelling moment in the oral argument that gave me some hope and sparked an idea about how state charter school boards could minimize the damage of a negative Supreme Court decision: focus on the question of a school’s mission.

At one point during the argument, Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Ketanji Brown Jackson offered a hypothetical question. If the government wanted to commission a mural and a religious painter wanted to include religious images, could the government reject that approach? Yes, said James Campbell, the attorney for the charter school board, because in that case, “the government is trying to speak its own message on its own buildings.” He claimed that the charter school law in Oklahoma, by contrast, gives “broad autonomy to the schools to come up with their own mission.”

Under that logic, what if charter school laws were amended to say that applicant schools were free to identify a number of missions, but that they had to identify as their ultimate mission teaching the liberal democratic values that bind together Americans of all backgrounds? That’s already a central premise built into the constitutions and laws of many states. As Albert Shanker, who first brought the idea of public charter schools to the national stage, argued, the primary mission of public education is to teach these values, which is bound up in “what it means to be an American.”

Teaching liberal democratic values is probably consistent with the approach of most religious charter schools, but few are likely to agree that this is their most important mission. The Oklahoma school at the center of the Supreme Court case, St. Isadore of Seville Catholic Virtual School, says its “ultimate goal” is “eternal salvation.” For many religious leaders, saying that promoting liberal democracy is their school’s primary mission would constitute blasphemy. When former President Joe Biden called the ideals in America’s founding documents “sacred,” a Catholic priest objected in the pages of the Wall Street Journal, saying, “America isn’t sacred. Only God is.”

The test for charter school applicants wouldn’t be religious; it would be one of mission. Not every religious school would fail the test, and not every secular school would pass it. If the government is entitled to “speak its own message on its own building,” why can’t a state ask the schools it funds to advance as their central message the preservation of liberal democracy?

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)