Journalist David Zweig Calls COVID School Closures ‘A False Story About Medical Consensus’

New book finds lousy COVID decisions everywhere, with experts basing assertions about the coronavirus virulence on flawed models.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Just a few weeks into the COVID pandemic, veteran New York journalist David Zweig began looking into the evidence behind universal school closures.

In early 2020, the findings suggested that children were essentially unaffected by the virus and minimally contagious when they caught it. He envisioned a magazine piece arguing for reopening schools, and began pitching it to major outlets.

No one was interested.

Eventually, WIRED agreed to run it, and as he reported it, the evidence only seemed to build. In New York City, just seven out of more than 14,000 deaths at the time were reported in people under 18. He remembers thinking: “This is a major, major story.” As the magazine took its time with edits, he was in a panic, “waiting to get scooped” by other media.

It never happened.

He soon realized that most major outlets had little curiosity about the science — or lack of it — underlying COVID remediations.

His piece, The Case for Reopening Schools, appeared in mid-May and instantly went viral. But its premise — that the U.S. was following “a divergent path” on reopening — got lost in the larger debate swirling in major media. And Zweig, a former magazine fact-checker who had always entertained the notion that health authorities and journalists in legacy media took science seriously, began to wonder what he’d missed.

A year later, with his two kids still not back to school full time despite mountains of evidence that it could be done safely, his sense of who the “good guys” were had been thoroughly shaken. Social isolation, masking and hybrid schooling were taking an enormous toll on his kids and millions of others nationwide, even as most schools in Europe opened early and stayed open, often without the dogged reliance on masking and distancing that American schools employed.

“The sense that all of this suffering for them and millions of other kids was for naught consumed me,” he writes. “I could not silence the voice in my head that this was gravely stupid.”

By 2021, he was testifying as an expert witness before a U.S. House of Representatives subcommittee on reopening schools, as well as a House subcommittee on the pandemic.

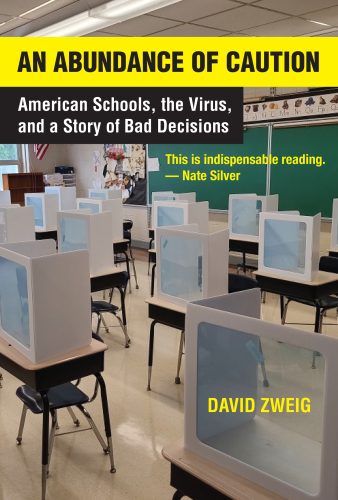

Five years after the first school closures, Zweig’s third book, An Abundance of Caution, out Tuesday, looks back on what he considers the questionable deliberations surrounding COVID at almost every level. While it takes the pandemic as its subject, Zweig notes that the book is about something much broader: “a country ill-equipped to act sensibly under duress.”

He finds bad decisions everywhere, with experts basing assertions about the virulence of the virus on flawed prediction models that themselves were based essentially on guesswork. Media outlets, he alleges, routinely overhyped the seriousness of the virus, despite evidence that children were not major carriers — and schools didn’t drive transmission.

The media perseverated on the effectiveness of remedies like masking, social distancing and isolation, Zweig finds, despite thin evidence that any of them made a difference. For months, they credulously transcribed experts’ predictions, often relying on the loudest, most overwrought voices, who often brought questionable credentials to the task. In one instance, an expert quoted on reopening was actually a consultant for smokeless tobacco companies.

Lawmakers dropped the ball as well, he says, prioritizing — perhaps even fetishizing — ”safety” over normalcy, even when there was little evidence for keeping schools closed beyond the few weeks in which public health experts urged Americans to “flatten the curve” of COVID cases.

Zweig has found a receptive audience for his reporting on the center-right — the book this week was excerpted in the conservative online publication The Free Press — but his work has also bolstered arguments in left-of-center publications, from Vox and The Atlantic to New York magazine and The New York Times.

Ahead of the book’s publication, Zweig spoke to The 74’s Greg Toppo, further exploring its themes of a false medical consensus amid America’s “uniquely acrimonious and tribalist political environment.”

Their conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

By May 2020, schools in The Netherlands, Norway, Finland, France, Switzerland, Germany, Spain, and more than a dozen other nations had reopened, with evidence mounting that COVID wasn’t even a modest risk to children. At a European Union conference, researchers reported that reopening schools there brought no significant increase in infections. Why weren’t we in lockstep with Europe?

That is a very good question, which I spend 500 pages discussing [Laughs]. I’m saying that jokingly, but I’m not joking. The answer to that is long and complex. A uniquely acrimonious and tribalist political environment in America is one large reason. It’s not the only reason, but it is a significant reason.

You bemoan the politics surrounding the pandemic, but in one instance you quote Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine on mitigation efforts. Early on, in March 2020, he talked about wanting to act aggressively. DeWine invoked the example of St. Louis, which did so in the 1918 flu outbreak and had a death rate of just 358 per 100,000 people, while Philadelphia was slower to respond and suffered 748 deaths per 100,000. “We all want to be St Louis,” he said. Part of me wonders: What’s wrong with that? Motivating people to not be the bad example makes sense, doesn’t it?

The example that so many politicians and so many media outlets used from the 1918 pandemic, where they often compared St. Louis to Philadelphia, was a deeply flawed misunderstanding of what the data actually showed over time. This was a misrepresentation and misunderstanding about what school closures can actually accomplish over time.

What’s the basic flaw in that approach?

A core flaw in the entire pandemic response, and in particular school closures, was the assumption that everyone was going to remain home and sequestered from each other for a lengthy period of time. While these interventions could be effective for a week or maybe two weeks or so, over time there is no way of effectively stopping the spread of a highly contagious respiratory virus in a free society, and in particular a society as economically and professionally stratified as America.

From the beginning, a significant portion of people in our country continued to move about because they had to. So while the laptop class sat home, and their children were home in a comfortable room, possibly aided by tutors or maybe a pod teacher, or maybe they were in private school, a significant portion of our country were delivering food and goods and other services from warehouses and restaurants and slaughterhouses to the wealthier Americans who sat at home on Zoom.

This was one of the most class-based, inequality-thrust decisions in our recent history. And to make matters worse is the idea which was continually perpetuated, that if you didn’t comply, that you were immoral, that there was a tremendous amount of virtue attached to the notion of staying home. Yet a significant portion of society could never comply with that. Beyond professional obligations, there are many millions of children who live in homes that are not safe, that are not conducive to being sequestered in a room for hours upon hours and sitting in front of a screen that they were supposed to learn from.

This whole idea that closing schools was going to have any impact was just manifestly absurd from very early, and there is just an endless amount of evidence, much of which I observed myself as a parent over time: Kids are going to interact with each other no matter what, and particularly when you think about kids whose parents had to work. What happened with them? Did they stay home alone? Some did, but many of them went to a grandparent’s house, a neighbor looked after them, or they went to a daycare or other situation where they were intermixing with children from a whole variety of nearby neighborhoods and towns. What I show is that this whole hybrid model, where schools were only open two days a week for some kids, or less, with the idea that that was going to mitigate transmission, was nonsensical, and there are tons of data that show this.

“There is no way of effectively stopping the spread of a highly contagious respiratory virus in a free society, and in particular a society as economically and professionally stratified as America.”

You can look at cellular phone data, and you can see the mobility of American citizens began to increase over time. What we can see is that this completely is in line with what scientists had known for many, many years: People’s ability to comply with unpleasant or difficult directives understandably wanes over time, and there was never any inkling that human beings, by and large, were going to all just imprison themselves and be hermetically sealed. Only the most motivated and financially capable people could and would actually achieve that.

It sounds like you’re saying that we were asking schools to do something that virtually no one else could do.

Even if schools were closed, the point is that children were still mixing with people, and the adults themselves were mixing as well. Lockdowns in a free society do not work over time. There’s some evidence that perhaps they could work if they are absolute and total, where every single thing is closed for a very brief period of time. But the idea that children were locked out of a school building while adults could go to restaurants and bars and casinos and offices and stores — the idea that that logically was going to have any impact — was absurd. Yet it continued for more than a year for many children.

Including yours. At a certain point in summer of 2020, it seemed as if schools might reopen in the fall. And then on July 6, President Trump tweeted, all caps, “SCHOOLS MUST OPEN IN THE FALL.” As you write, four days later, the American Academy of Pediatrics came out opposing reopening. They had argued “forcefully and unambiguously” for opening schools before this. How much of this disaster was, as you say, Newtonian physics in the political realm?

The equal and opposite reaction.

Trump is for it? I’m against it.

It’s quite stark. The example from the American Academy of Pediatrics is quite stunning. The about-face was so obvious that even NPR wrote about it. But that’s just one example. Throughout the book, I show over and over how people on the left were just reactive against Trump, and even those who wanted to talk about what they thought was wrong often generally didn’t do so.

I had doctors, many of whom were at prestigious institutions around the country, reaching out to me, talking — always off the record — about how they vehemently disagreed with what was going on in schools: Mask mandates with kids, if the particular schools were open, or quarantines, or barriers on the desks, the six feet of distancing — all of these things that we were told were critical and that there was a consensus, and that this is “what the experts say.”

“People on the left were just reactive against Trump, and even those who wanted to talk about what they thought was wrong often generally didn’t do so.”

All these things were a manufactured consensus. This was artificial, and unfortunately, I couldn’t talk about it that much because all of this was off the record.

Many of these doctors and others, including former CDC officials who would reach out to me, were simply afraid of being cast out amongst their peers. But many of them also were very explicitly told by their administrators, by their bosses at their university hospital or whatever institutions they were with, that they were not allowed to say this. They were not allowed to go against the narrative of the CDC. To me, that’s a far more frightening form of censorship, that the American public was misled in part because there was a false story about a medical consensus. I had access to this information, knowing it was a false narrative, but I was constrained in what I could say. But I will say this: That sort of false narrative continued, not just from doctors who were contacting me and other health experts.

All we had to do was look at Europe: Tens of millions of children were in school there. But by and large, the media ignored this — not just the media, but our health officials. Or they contrived a variety of reasons that were false about why those kids were in school there.

That actually leads me to my question about journalism: You seem to hold a special disdain for the coverage of the New York Times, which you feel set the tone for fearful, expert-based coverage that largely ignored evidence. What happened, and how did things go wrong so quickly there?

Well, I single out the Times only because they were particularly egregious in their misleading coverage about the pandemic in general and in particular about children in schools. It’s not exclusive, I talk about all sorts of media outlets, but there’s extra focus on the Times because arguably it is the most influential news outlet in the country, certainly amongst the elite decision makers in our culture, whether in politics or other fields. It’s very important for how policy gets made in our country. The framing that The New York Times puts on certain topics is very important.

If you think about Israel and Palestine, people already have kind of baked-in positions on that largely, so the framing of the Times will probably just anger one group or another, depending on the story. But something like the pandemic, this was new. So people didn’t come at it with a preconceived idea. They came somewhat blank-slate, at least among the broader kind of political left who reads The New York Times. The Times is telling them, “Don’t look over there. Don’t look at what’s happening here,” and if you do look then they give you a horror story about a school in Georgia without providing any context, or a horror story about Israel without providing any context.

So one of the important things that I hope readers come away with after they finish my book is an understanding about how media can be incredibly misleading without necessarily publishing errors or facts that aren’t true; that you can write something that’s fact checked, and it still can be incredibly misleading by the way the story is framed, by the information that’s left out, by who you choose to interview and quote. All those things are incredibly important regarding how people perceive reality, and you can do all of it without having any errors.

I want to ask about your kids. How are they doing five years later? I guess they’re now in eighth and 10th grade?

That’s right.

How do they see this period of their lives?

They’re like any other teenagers. It’s impossible to have specific correlates for most circumstances, to say, “Pandemic school courses now have led to X in my child.” We, of course, can look at broader data, and rightfully so. There’s a lot of focus on “learning loss” and test scores. And there are a number of studies that clearly show a direct correlation: The less time that kids were in school during the pandemic, the worse their educational outcomes and scores were. We know that it’s directly linked to that. There’s no ambiguity.

“To me, that’s a far more frightening form of censorship, that the American public was misled in part because there was a false story about a medical consensus.”

But what I talk about in the book is that there’s so much that happens in life that you can’t quantify. If you just think about what happened to the high school football player who was relying on a scholarship in order to get into college, but the senior year season was terminated. Never happened. What happened to that kid and so many others like him? What happens to the kids who relied on their school theater program or arts programs?

What happened to the kids who relied on teachers to report abuse at home, because teachers and educators are the No. 1 reporter of child abuse. When schools were closed, those kids had nowhere to go and no one to see what was happening. So a perverse thing happened during the pandemic: Child abuse reports actually went down. But it’s not because there was less abuse. It’s that children lost this important vehicle to actually bring what was happening behind closed doors into the light. Harm is incurred whether there’s a lingering effect or not.

I’m glad you brought up abuse because that’s one of those things people don’t necessarily see right away.

This was known immediately. In April 2020, they already could see this. The data were already coming in. So to be very clear, health officials knew harm, great harm, was being done to many children, and they continued with the school closures nonetheless.

A lot of “blue” parents say that COVID radicalized them. And I wonder how you’d describe what it did to you?

I wouldn’t say I’ve been radicalized, but I would say as someone who, generally, for my whole adult life, had positioned myself pretty far on the left, I have always been an independent thinker. I’m not one to go with the crowd. I’ve been independent politically. But observing the way our health authorities behaved in conjunction with legacy media, both of which are predominantly on the political left, and observing the complete disconnect from science, from following evidence, from a clear-eyed, honest view of empirical reality, was incredibly destabilizing. You can never go back from that once you observe that type of behavior.

“Observing the way our health authorities behaved in conjunction with legacy media, the complete disconnect from science, from following evidence, from a clear-eyed, honest view of empirical reality, was incredibly destabilizing.”

These were supposed to be the good guys. I’m not saying this was purposeful, necessarily, or conscious, but people’s hatred for Trump and hatred for Republicans or people on the right so dramatically distorted the lens through which they were seeing the world that they conducted themselves in a fashion that was completely disconnected from reality. One of the great ironies of that era was these lawn signs, “In this house, we believe in science.” These people with the lawn signs generally had absolutely no clue what the science said. They had no clue what they were talking about.

What I’m left with after reading the book is just this kind of sick feeling about what’s going to happen the next time, in the next pandemic. I wonder if you have a sense.

It’s so hard to know. I would just close by saying that I hope my book can do a small part in trying to reveal how the views of society, and in particular, of elite society, spin. My book is essentially one giant case study, composed of a series of case studies, of how health officials and the media operated. And by reading through this narrative of these case studies, you gain a deeper understanding about how things actually work, how individuals and societies make decisions with limited information. Hopefully, people will be armed with that awareness and knowledge. So whatever the next crisis is — it doesn’t need to be a pandemic — you’ll have a more clear-eyed and educated view about what’s actually going on around you. And perhaps that will be able to ultimately change what’s going on around us.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)