Scholar Douglas Harris Debuts New ‘Wikipedia’ of K–12 Research

As cuts threaten insights into K–12 schools, the veteran researcher is helping to build a compendium of education insights.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

The actions of the Trump administration over the last few months could make it vastly more difficult to understand what’s actually happening in schools.

Already, the president’s team has announced the cancellation of dozens of contracts through the Institute for Education Sciences, the Department of Education’s research arm. Over 1,300 of the department’s employees, amounting to roughly half of its workforce, have been terminated, casting doubt on whether key functions like national testing initiatives can carry on without interruption. And the future of dedicated learning hubs, including one credited with triggering a breakthrough in reading instructions, is in serious doubt.

The wave of cuts and firings was the unspoken agenda item at the 50th annual convening of the Association for Education Finance and Policy, one of the most prominent professional organizations for education researchers. In mid-March, amid three days of panels and paper sessions touching on every conceivable topic in K–12 schooling, hundreds of academic economists, education activists, graduate students, and district staffers exchanged concerns about the future of public insight into schools.

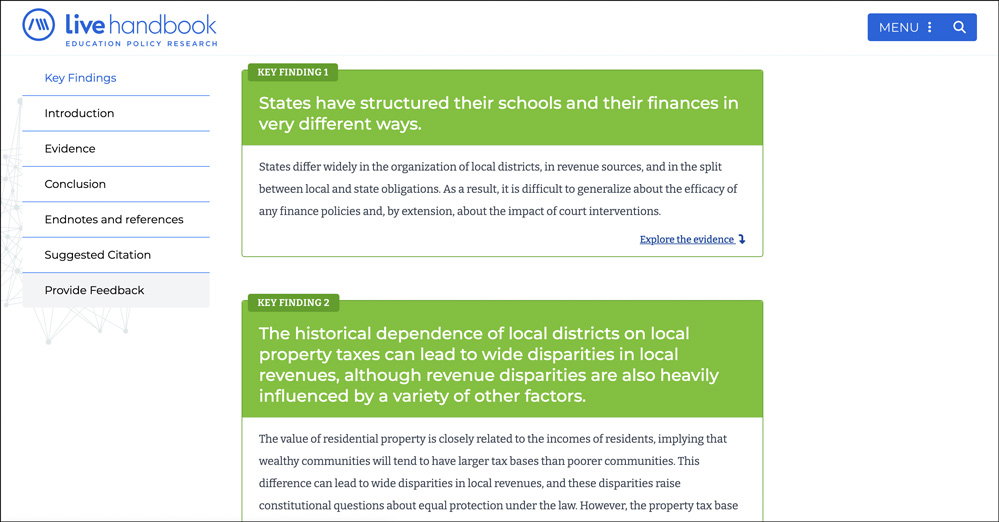

Ironically, those worries emerged just as AEFP unveiled a critical new tool: its Live Handbook of education policy research, gathering and distilling the findings of thousands of studies. Its 50 chapters address a bevy of questions ranging from preschool to higher education, including the makeup of local school boards, performance of charters and school vouchers, teacher preparation programs, the effects of education spending, and more. The Association hopes the extensive and growing site, an update of previous printed versions, can provide educators and lawmakers alike with something akin to a Wikipedia for research.

Leading the effort is Tulane University economist Douglas Harris, a veteran researcher who also heads the Education Research Alliance for New Orleans and the National Center for Research on Education Access and Choice. An expert on charter schooling, Harris has been one of America’s most productive scholars studying how district, state, and national policies shape what kids learn — and addressing some of the most contested questions in the field, including whether school choice actually improves the delivery of education.

In a conversation with The 74’s Kevin Mahnken at the conference in Washington, Harris talked about the origins of the Live Handbook project, how its creators intend to ward off ideological bias, and why IES and other federal research efforts are irreplaceable supports in the U.S. education infrastructure.

“In some sense,” he said, “the Live Handbook is a monument to IES, at a time when IES is being knocked over.”

What’s the purpose of this project?

The idea is to make research more useful and make researchers more useful. One of our purposes is to just get research summarized and discussed in a way that’s actually accessible to a broad audience, and another is to connect researchers to policymakers and journalists. If you’re looking for an expert on an issue, you can find their names in these articles, click on them to get their information, and just email that person.

We’re hoping users create these networks of expertise and connect them with people who need that expertise.

I have to say, it sounds like you’re trying to put education journalists out of work.

[Laughs] No! Part of what we’re doing is offering journalists something they can easily cite. One of the exercises I told people to do when first developing this idea was to just see what they got after searching the internet for a summary of research on their favorite topic. The results were not very heartening.So I think this will be very useful for journalists, who will be able to find something much easier and link to it in their stories. And hopefully, when somebody is searching for a topic, the handbook will come up as the top result, which will make it build further. The more reach it has, the more people will want to write for it, and the more existing authors will want to update it — which is another important part of the document. It’s not just static, it’ll be updated every year, and all the authors will be expected to continue working on it. If they decide they don’t want to do that, they’re going to hand it back to us, and we can turn over the authorship to somebody else.

That kind of arrangement is actually unusual from the standpoint of intellectual property. We weren’t sure how that was going to work at the beginning, or if it was even legal to do it that way. But it turns out that, as long as everyone is clear about it, you can write the agreement that way. Part of the motivation for this project was to marry the traditional handbook with Wikipedia, but with Wikipedia, there’s no issue with authorship.

I didn’t realize you took inspiration from Wikipedia.

Well, there had been some talk of doing another handbook, which we’d been doing just about every decade. They were all about 700 pages long, there’d be 30 or 40 chapters written both for and by academics. We’d mostly use them as syllabi and readings for education policy classes, but the only real audience was other AEFP members.

The other inspiration emerged from our website at Education Research Alliance-New Orleans. We had something like 40 studies on our website, and the page with key conclusions was like an integrated summary. All this evidence was just for the relatively narrow topic of school reform in New Orleans.

The question we were asking ourselves, and which you should always ask if you’re writing something, was who our intended audience was. What we realized that we didn’t have to choose between researchers and policymakers. The beginning of each entry looks like a policy brief, and non-researchers will probably stop when they get to the last key finding. But if you want more detail, you just click on that finding, which takes you to the longer discussion that would have been included in a printed version of the handbook. If you want even more than that, you can click on the endnotes, which will hyperlink you to the underlying studies themselves.

So you’re serving everybody: At the top, policymakers are your main audience, but by the time you get to the bottom, the researchers and experts in the field can dig in.

Up to this point, would you say that education research has been effectively communicated to the public, and that it has informed how politicians create policy and oversee schools?

Uh, hard no. [Laughs] We have not done a good job with those things.

There have certainly been moves toward that. There’s something called the Research Practice Partnership movement, which is supposed to develop genuine partnerships between the research and policy worlds, and it’s great. But they’re really hard to create and sustain, and they tend to be very localized. We wanted to do something that had broader research.

“Recent studies tend to be methodologically better — again, partly because of IES and the principles and demands that IES has placed upon us.”

We’ve also got the What Works Clearinghouse, which is federally funded. If you look at those releases, though, they never realized their potential. They were too slow, they were written by committee, not very readable. All of this was aiming in the right direction, but not hitting the target well. There was clearly a hole there that we’re now trying to fill.

As you mentioned, the What Works Clearinghouse is a federal resource that’s only a few decades old — although, given reports that its funding has been cut, it may not get much older. Is the need for a live handbook related to the fact that the social science around education outcomes doesn’t go back very far?

The federal government certainly led the way in moving toward evidence- based policy. And everything I just mentioned emerged out of that orientation, which was mandated by law around the time of No Child Left Behind and is still in effect today.

There is also a natural demand, in the sense that people want to do the right thing. They want to make their K–12 schools and colleges better, and they want advice. But advice is usually pretty ad hoc; it depends on who’s in your network, who’s got a friend in a school nearby, and what they’re hearing. There will always be a place for that, but having actual evidence at the root of those conversations has a lot of potential to improve things.

Can you think of an area of research where the evidence has managed to break out of academic discourse and influence the public?

Research doesn’t drive most conversations about policy and practice, but it can have influence at the margins and create new ideas. The science of reading is the example that comes to mind immediately. Russ Whitehurst, who became the first director of IES, is a psychologist, and he was the one who really emphasized the reading research. Almost all the underlying evidence for that is IES-funded research, which is noteworthy under the current circumstances.

Another example would be class-size reduction. There was a lot of interest in that for a while, until it became clear that, while it works pretty well, it’s also very expensive. The school funding debates, and whether money matters in student learning, would be another case.

I think people can get their arms around class sizes and budgets being important issues in schooling. But even for someone like me, who has experience consulting research, it can be very difficult to weigh the evidence that various experts marshal on questions like teacher evaluation or early childhood education.

That’s the hole we want to fill, right there. We want you to do that google search and come to what we’re doing because we have answers to those questions.

We’ve got 50 chapters in this first round, and the plan is to update each of those next year while adding another 25. Part of it depends on funding, and growth is very time-intensive. We have to do all the things that a publisher does, putting it on the website and creating PDF versions and all that. But the idea is to grow the handbook so that it becomes comprehensive, both in terms of covering every part of education — early childhood through higher education — and also trying to cover all the key policy areas.

How comprehensive is comprehensive? There are really old, but foundational studies, like the 1966 Coleman Report on segregation and achievement gaps, which were conducted when methods were much more crude. Are you trying to include that kind of evidence?

What we’re doing is an awful lot without also trying to write the history of education research. The most recent research is obviously more relevant because context matters. The world is changing around us, and that affects education. So we want more recent studies.

Another important thing to remember is that recent studies tend to be methodologically better — again, partly because of IES and the principles and demands that IES has placed upon us. We’re telling authors to focus on the most recent and best studies, because those are going to be more useful to the field.

In some areas, like school finance, the debate among leading researchers still burns very hot. I’m sure it’s difficult to arrive at anything like a consensus, so are you just trying to represent the state of play?

It’s a challenge. From the beginning, we didn’t expect that we would release these chapters and people would say, “Oh, you’re exactly right!” Sometimes they’ll say, “Wait a second, I don’t agree with that.”

I wrote the charter school section, and we showed it to a group of policymakers and practitioners who are advising us. We brought them into the design process to make it more useful to them, and when I was doing a show-and-tell a couple of weeks ago, somebody said, “I’m not sure I agree about your point on charter schools!”

We knew that was going to happen. So we’ve advised the authors to present different sides of the debate — the major positions that are pretty widely known — and, if a key finding falls clearly on one side, then at least address what the other side of the argument is. We’re being really clear about the evidence base, and I can’t just say, “Such-and-such is true of charter schools because I feel like it.” It has to be because one group of charter studies is stronger than another group of studies, or there’s something really unusual about the context of some studies that make them less convincing. Basically, there has to be a reason that addresses the different sides of arguments.

What structures have you put in place to prevent a kind of ideological drift?

Our editorial board helps with that. It’s a very wide-ranging group where you have some people who are seen as more on the left, and some who are more on the right. There are people from different disciplines. We’ve encouraged authors to include studies from outside their disciplines; quantitative people should include qualitative work, and vice-versa.

“It’s very worrisome, and I think we’re at a really uncertain time. I don’t think IES is going to go away. But we don’t really know what direction it’s headed in or how long it will take to get there.”

The board is there to enforce that and make sure we were getting the right range of perspectives, so that when there are disagreements, someone can say, “Hold on a second, you’re missing something.” We’re not going to be perfect in the first round, but the process is set up to be updated and receive feedback. If you’re reading a piece and have a question, or you want to debate some point, you can click the feedback link and explain it. We’ll send all that information to authors, and once a year, they’ll be expected to go through those comments. If we see significant issues with a piece, we’ll push them to update it.

And I imagine the various writers and editors can weigh in on other entries as well.

Here’s the way we handle these discussions: I wrote the charter schools chapter, which was edited by [University of Arkansas professor] Patrick Wolf. He’s the one pressing me on the evidence there, but I’m the editor for his section on school vouchers. We view those topics a little bit differently, but that’s a way we enforce objectivity. We recognize that everybody’s subject to that sort of bias.

That’s an interesting pairing. From my perspective, the public debate around charter schools — which has been extremely contentious in the past — has become somewhat quiescent, while the voucher issue has just roared into prominence over the last few years.

There are a lot of studies in play on vouchers, so Pat will probably have to update his chapter next year, and every year after that. Much of the research in that area is old and based on the city-based voucher programs in places like Milwaukee or Washington. Then you had the four states where we could study statewide voucher programs, which are probably the most relevant to the current discussion. And we’ll also be including three or four national studies that we’ve got going at the REACH Center, which I lead.

Part of the problem with the way the new voucher programs are set up is that, in a sense, they’re designed not to be studied. There’s no state testing requirement, so we don’t have test-based outcomes, and you’re confined in what you can study. Still, there will be a lot of interest in that topic.

What do you make of the cuts to federally supported research that have been announced over the last month?

It’s a very big deal. If you look at the endnotes for this handbook, probably half of them have a basis in IES. Either the studies themselves were funded by IES, or they’re using IES-funded data sets, or they’re written by researchers who were in the IES pre-doc or post-doc programs. There was a whole set of training programs that were designed to develop the next generation of scholars. So in some sense, the Live Handbook is a monument to IES, at a time when IES is being knocked over.

It’s very worrisome, and I think we’re at a really uncertain time. I don’t think IES is going to go away. But we don’t really know what direction it’s headed in or how long it will take to get there, given that they just fired essentially everybody. The best-case scenario is that they hire a new director who’s allied with the administration and who has sympathy and a desire to build it back up. There’s no question that there are ways the institute could be made better, but there are also a lot of things you’d want to keep about the old structure.

It’s good to have decisions made by people who are researchers and know the field. It’s good to have policymakers involved in decisions about what gets funded, which has been true for a long time. Should the research process be faster? Sure, we could find ways to do that. So it’s possible that IES comes out better at the end of this. But will it? It’s a huge question right now.

There’s obviously a lot of concern at a conference like this, where people have seen IES as the root of so much of the work we’re doing.

Virtually every researcher I’ve spoken to has said something similar. People will generally concede that improvements can be made, but where the process calls for a scalpel, DOGE is using a dump truck.

I think that’s right. In the amount of time they had, they couldn’t have possibly learned what grants or contracts should be kept. If you’re trying to do it based on reason, there’s no way to do it in a matter of weeks. It’s been very arbitrary, just searching for keywords and things like that. It’s no way to fix anything, it’s a way to knock things down.

Something people don’t realize is how long it took to build IES to begin with, and to gain support for it. It started, I believe, back in 2001, and it took a long time to build up the staff and the expertise. Especially in terms of data collection, it’s just underestimated how much expertise goes into what IES does. All these contracts with Mathematica and AIR depend on those organizations’ very significant internal capacity in areas like getting schools and students to respond to surveys. It doesn’t just happen. There’s so much expertise that goes into those tasks, which you’ve now destroyed.

Even if they succeed in making things better in other ways, that’s going to make it much harder to build back the things they should want to keep. It’ll be like a wave pushing against them.

Mark Schneider, the IES director under both Presidents Trump and Biden, told me that the original intention was for the institute to grow much more substantially than it has, until it more closely resembled a $40 billion agency like the NIH. Even though that hasn’t happened, it has punched above its weight in expanding the knowledge base about schools.

Oh, absolutely. When you think about what a good organization of any kind spends on R&D, it’s a much greater proportion than the IES budget relative to total education spending. IES has about a $1 billion budget, and the United States spends something like $700 billion per year on education. So that’s less than .2 percent. It’s less than any standard you could come up with.

“If you’re trying to do it based on reason, there’s no way to do it in a matter of weeks. It’s been very arbitrary, just searching for keywords and things like that. It’s no way to fix anything, it’s a way to knock things down.”

It’s always been underfunded, and they use those resources well. Collecting data, for example, creates so many positive spillover effects because once you’ve collected it, anyone can use it. The pre-doc and post-doc programs are really important for producing people who can work at school districts and state agencies, which need professionals who are really trained in research. That may go away too.

One of the things that doesn’t get enough attention is that the federal government was very involved in creating the state longitudinal data systems, which have played an enormous role in just about every area of policy research. The federal government gives money to the states to create those systems and make them available, and they allow us to link schools and programs to student outcomes. Without that, you’ve got nothing.

You mentioned that IES was instrumental in generating research on the science of reading, too.

That’s probably the best example of the organizational influence. It’s not so much about the data they were collecting, but it was related to the projects they were funding. It’s also a good example of something Republicans support. They’re all about the science of reading, but what’s happening is that they’re basically undercutting the next science of reading.

There might be some research studies that don’t seem very useful, but in a way, that’s the point of research. You don’t know what’s useful until you actually do it. We don’t know what the next science of reading is going to be. Hopefully, the Live Handbook will help find it, but we’d find it faster with IES underpinning the research that will get us there.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)