In School Finance Discussion, Experts Warn That Economic Damage From COVID Could Force ‘Unheard-of’ Cuts

On April 16, 74 Senior Reporter Kevin Mahnken moderated a webinar for education journalists hosted by the Education Writers Association. The discussion, titled “What Does the Coronavirus Recession Mean for School Finance?,” was intended to assist reporters as they cover the incipient economic downturn triggered by the COVID pandemic.

In a public conversation last week about the effects of the COVID-19 outbreak on education budgets, two school finance experts voiced concern about the extent of the economic havoc unleashed by the disease — as well as uncertainty around how various states and districts will manage the fallout.

The finance-focused webinar, hosted by the Education Writers Association, included guests Karen Hawley Miles, president of the nonprofit Education Resource Strategies, as well as independent financial analyst Michael Griffith. The duo, who have spent years studying educational spending and advising school districts on financial management, took questions from reporters on the likely impact of a coronavirus-induced downturn and extracted lessons from the experience of the Great Recession.

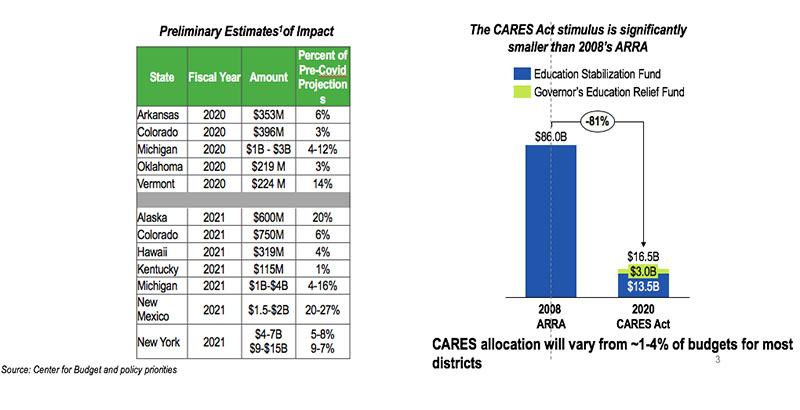

Griffith outlined the latest round of federal assistance for public education included within the $2.2 trillion CARES Act that Congress passed in late March. The colossal relief package offered $16.2 billion in funding that could be used for K-12 schools (though nearly $3 billion of that is left to the discretion of governors, who could use it to buttress public universities). By Griffith’s calculations, that sum amounts to $286 per student, or a roughly 2 percent spending increase.

While helpful, he said, that level of aid isn’t commensurate with the scale of the fiscal distress facing states, which are seeing revenues from income and sales taxes fall through the floor. Just a few weeks ago, Griffith said that he was predicting the resultant budget cuts to fall within the range of 10-15 percent; that number has since grown exponentially.

“Now I’m hearing states that are talking about a 30 percent cut,” he said. “That’s unheard of. To put this in perspective, the revenue cuts that we saw in education from states during the last recession were about 7.5 percent, so this could be four times the impact of the last economic downturn.”

Within the past few weeks, a coalition of education advocacy groups has circulated a proposal calling for an additional $200 billion in emergency education funding, an amount that Griffith said would come closer to meeting the budgetary challenges that will arise in the next few years.

At the same time that tax receipts are collapsing, Hawley Miles added, students’ academic and social-emotional needs will undoubtedly grow as the pandemic continues. Many children will begin the 2020-21 school year far behind in their studies, and some will have incurred lasting psychic damage as well.

“The impacts on need will be unequal across students, families and communities,” she said. “And schools may need to plan for [further] temporary shutdowns, which adds additional cost.”

While local policymakers look for every opportunity to keep costs low, Hawley Miles observed, a sizable number of schools are also continuing to pay sidelined hourly workers “because so many of these districts know that they are the major employers in their cities, and many [school staff members] are the parents of students in their schools. So there’s a huge ripple effect.”

One difficulty during economic downturns for both journalists and financial officers is helping school communities understand the cost of budgetary shortfalls in terms more urgent than credits and debits, Griffith said, noting that he wished analysts had better communicated the human cost of slashed educational spending during the Great Recession.

“For the public, when we talk about dollars in budgets, or percentages, that doesn’t really mean much to them,” he said. “When we talk about programs that are eliminated, when we talk about things like kids now having to walk two miles to school because busing has been reduced, that kind of stuff people understand.”

Asked what kinds of economic questions education reporters should ask of local officials, Hawley Miles pivoted from finance to technology. As public education transitions from in-person to online learning, unfair disparities abound between relatively more and less affluent schools and districts, providing an opportunity for journalists to tell a story that might have otherwise been obscured.

“We’re learning a lot of great things, and a lot of negative things, about distance learning right now. There’s huge [inequality] across districts and states, and even within districts, in access to technology, engagement with it and support from teachers. This seems like an incredible time to be writing stories about this and collecting data to try to understand what’s working and what’s not.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)