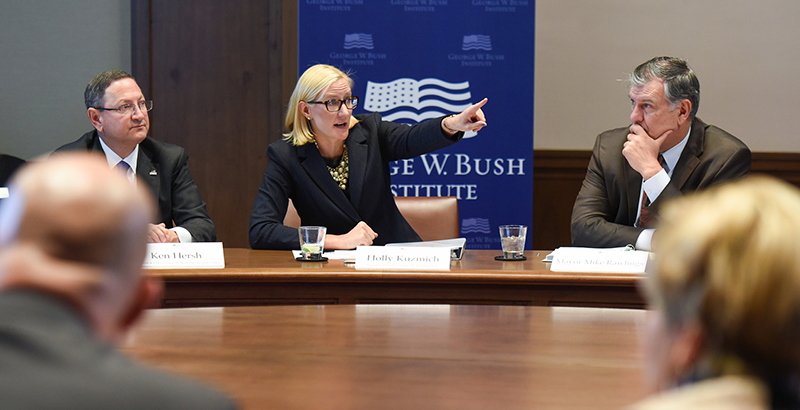

The ‘A’ Word: Holly Kuzmich — ‘Many of the Challenges Still in Place Can’t Be Tackled Via Policy Change’

This piece is part of The ‘A’ Word series, produced in partnership with the Bush Institute to examine how “accountability” became a “dirty word,” and what can and should be done going forward to ensure accountability withstands the test of a bad reputation. Click through the grid below to read the ‘A’ Word conversations.

Accountability — what does it mean today? We have been discussing this question for several years at the Bush Institute. We’ve always stood for accountability in education, but it seemed that instead of getting heads nodding in agreement when we talked about our work on accountability, there’s been growing skepticism of the concept. We wanted to talk to experts, those charged with implementing educational accountability at the federal, state, and local levels, which is what led to this series of interviews.

Upon reflecting on what each of these experts said, the good news is that the core principles of accountability that have guided progress in our schools are still widely agreed to: setting high standards, assessing regularly to those standards, measuring improvement, and providing supports for students and consequences for schools that don’t improve. Disaggregation of data is vital and has led to a focus on closing achievement gaps, especially for poor and minority students. Those basic tenets guide the work of these experts no matter what political party they are affiliated with or what position they hold.

But they also acknowledged the fundamental truth that policymaking is an imperfect process. No policymaker gets all the details right, and policymaking in and of itself requires different sides to bring together their varying points of view, which inevitably leads to some level of trade-offs.

(Click through the grid below to read other ‘A’ Word conversations)

This imperfect policymaking process has led to shifts over time in how accountability has been implemented at the federal, state, and local levels. The focus on accountability largely grew out of efforts by several states back in the 1980s and 1990s.

While some states were leading the charge, others were lagging behind, so the federal government took on a much more significant role through passage of the No Child Left Behind Act in 2002. But we’ve now seen a shift back to the state and local level with the perceived overreach of the federal government. The Every Student Succeeds Act keeps some of the fundamentals in place, but shifts authority for the design of accountability systems back to the state level.

No matter where the balance of control lies and what kind of progress we’ve seen to date, there still is serious room for improvement. The experts we interviewed outlined a series of issues that have yet to be fully addressed if we are to improve outcomes for kids and remove barriers that stand in the way.

Some of these issues should be addressed by policymakers, but many of the challenges still in place can’t be tackled via policy change. They instead are in the hands of administrators, school boards, teachers, parents, and engaged citizens. For example:

- While we have general agreement on the importance of an annual test to measure whether students are learning to read and do math on grade level, we still often find too much test prep in our schools. There is widespread support for the annual assessment, but an overreaction to that assessment with too much test prep.

- Parent voices in communities across the country are too often limited to a segment of parents — often white, upper-middle-income parents. But they are usually the minority of parents within a community, so it’s important that low- and middle-income parents are engaged and heard from as well.

- There’s room to grow the accountability system and look at not just how students do through high school, but beyond high school. Danny King in Pharr–San Juan–Alamo wants to know how students graduating from his South Texas district are persisting into higher education. That signifies a local leader willing to take ownership.

- Data receipt is often too slow to be actionable. For all the progress we’ve made on the use of technology to deliver real-time information, there are still serious lags in getting data and information to parents to understand how well their child is performing and whether they are on track.

- Finally, there was an acknowledgement from several experts on the disconnect between what accountability and data tell us and how resources are aligned — or too often misaligned — to the priorities that data tell us we should focus on. Kevin Huffman discussed that the billions of dollars that are spent on professional development across the country are often spent independently of accountability. It’s been a widely known fact that professional development dollars have been poorly implemented and targeted for years, and yet we’ve seen little change. That’s a significant set of resources that, if aligned more seriously to the needs of kids and teachers in a particular district, could make a real difference.

What was particularly encouraging from these interviews was the leadership each person has demonstrated. The implementation of accountability at the ground level can lead to different reactions. It can be seen as a tool for improvement or can stoke a culture of fear. These leaders all view it as a tool for improvement. They are committed to using data, and are not afraid to admit when more of the same is not working.

We could use more like them, and I hope they continue to lead. Our students will be better off for it.

Holly Kuzmich, executive director of the George W. Bush Institute, worked on educational policy issues at the White House and the U.S. Department of Education under President George W. Bush.

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

;)