Power Is Knowledge: New Study Finds That Wealthy, Educated Families Are Using School Ratings to Self-Segregate

This is the latest article in The 74’s ongoing ‘Big Picture’ series, bringing American education into sharper focus through new research and data. Go Deeper: See our full series.

If there’s one thing parents, real estate agents, and educators all understand implicitly, it’s this: High property values are built on top-notch school districts.

Excellent schools are considered so precious, parents will risk huge fines and even jail sentences by enrolling their children under false pretenses. Buyers, even those without children, are willing to pay hefty premiums to live in good districts, since their prices are resilient to downturns in the housing market. And real estate databases like Zillow, Trulia, and Redfin all include copious information on the proximity and quality of local education options.

In fact, a new study finds, the increasing ubiquity of school quality ratings may be changing the complexions of whole neighborhoods and cities, deepening the divide between rich and poor areas. The reason? As information on school performance becomes more widely available, the wealthy and well-educated flock to the areas with the highest-rated schools. Meanwhile, families and schools with fewer resources are left in their wake.

The study, conducted by Duke University professor Sharique Hasan and Anuj Kumar of the University of Florida’s Warrington College of Business, was circulated as a working paper late last year and is now undergoing peer review. It focuses on economic and demographic shifts following the emergence of GreatSchools, a nonprofit organization launched in 1998 that offers school quality information to parents.

While states are required under federal law to collect and disseminate data on school performance, GreatSchools is undoubtedly the most visible private entity providing K-12 school ratings. The organization rates schools on a 1-10 scale based on a range of metrics including test scores (and progress on testing over time), high school graduation rates, student performance on college entrance exams, and disciplinary records.

The aim of publishing these grades is to help parents — especially low-income parents, who may lack the time and social connections to consider all the schooling options available to them — make informed decisions on where to enroll their children. But the authors find that the information has had the unintended effect of making highly rated schools an exclusive destination for comparatively advantaged families.

“Across a range of specifications, we find that access to school performance ratings appeared to accelerate, rather than reduce, economic divergence across ZIP codes in the U.S.,” they write.

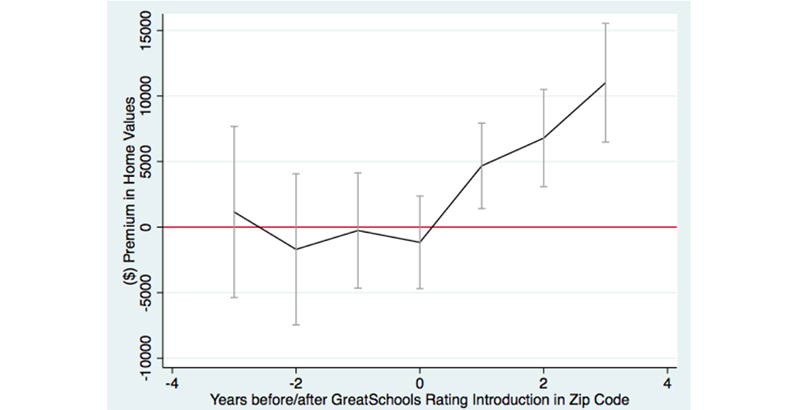

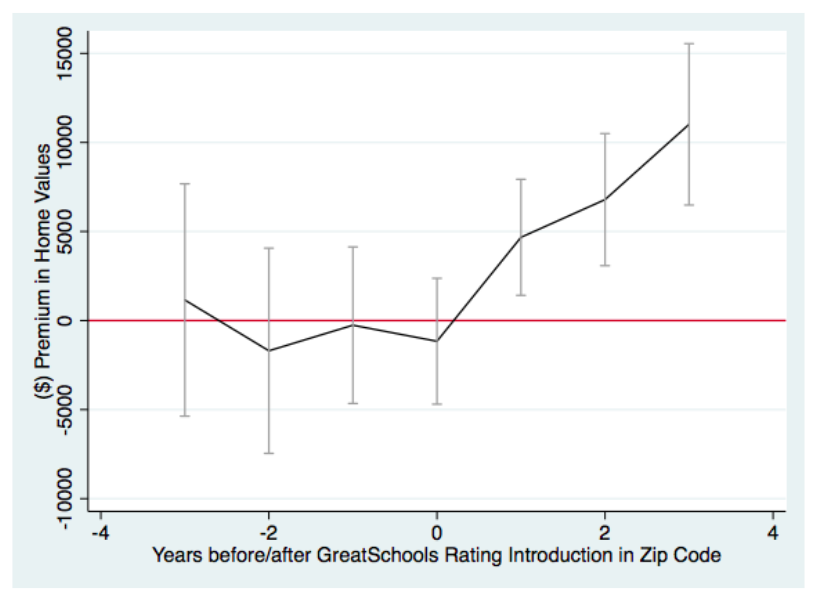

To assess the impact of school ratings on home values and demographic composition, Hasan and Kumar used home value assessments from Zillow both one year before and three years after GreatSchools first published grades within a given ZIP code. They also relied on IRS data on family incomes and census information on racial and ethnic makeup, forming a picture of the organization’s gradual rollout across 9,400 ZIP codes in 19 states.

Home values rose fairly quickly once the surrounding schools were graded highly by GreatSchools, indicating increased demand for housing there.

Among ZIP codes with schools of roughly equivalent performance (as measured by scores on state math exams), those rated by GreatSchools saw an increase in value of 3.49 percent over those that hadn’t yet been rated. Among ZIP codes whose student performance lay, respectively, one standard deviation above or below the average, home values diverged by $3,500 one year after GreatSchools ratings became available. After four years of GreatSchools availability, the disparity grew to $9,000.

The home values in those areas were moving in different directions because of the different profile of the people residing in them. Hasan and Kumar say their findings indicate “a widening gap in the proportion of high-income households in ZIP codes with low-performing schools and those with high-performing schools,” growing to as much as 1.6 percent four years after school ratings were made public.

White and Asian families were 2.6 percent more likely to live in neighborhoods with high-performing than low-performing schools after the same amount of time, they found, and college-educated families migrated to ZIP codes with high-performing schools at roughly the same rate.

In an email to The 74, Hasan and Kumar said that affluent and well-educated families are simply in a better position to act on the ratings provided by organizations like GreatSchools.

“Parents who have more resources will likely: a) have better access to [school quality] information and b) are better able to use it to move to better school districts (with more costly homes),” they wrote.

One complaint sometimes lodged at GreatSchools is that the metrics they use to assess schools — especially proficiency on standardized tests — can essentially act as a proxy for students’ income and family status. Critics worry that if advantaged children are more apt to excel on tests, and their test scores are likely to attract more advantaged families to their schools, such ratings may inevitably lead to increased concentration of wealth and status in a shrinking number of privileged communities.

Carrie Goux, vice president of public affairs for GreatSchools, wrote in an email to The 74 that the organization has recently overhauled its ratings system to account for that problem; measures of equity and student progress are now included in their calculations, which could draw more attention to schools that do right by low-income and minority students.

Goux added that GreatSchools was taking steps to make its ratings more accessible to all.

“It’s … very important to note that the data must get into the hands of those who need it most, and who may not seek it out on their own. We believe it is critical to partner with advocacy organizations working with underserved families and empower them with GreatSchools’ clear, understandable school quality information and data,” she wrote.

Hasan and Kumar call the changes to GreatSchools’s ratings system a positive development but warn that authorities should take greater care in wielding education data.

“Our findings suggest that both states and private organizations will need to think harder about what dimensions they rate schools on, but also how this information will be used and by whom. A step in the right direction would be for the states to collect more comprehensive and inclusive measures of school quality. In doing so, they should seek the input of diverse stakeholders (education scholars, non-profits, and parents). Moving forward, the mass collection and dissemination of information is inevitable. Whether it advances the interests of all families or just advantaged families is an open question.”

Disclosure: The Walton Family Foundation, Bloomberg Philanthropies, Carnegie Corporation of New York and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation provide support to GreatSchools and The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)