Newspaper Investigations of Toxic Asbestos, Lead in Philadelphia Classrooms Underscore Infrastructure Problems in Nation’s Schools, Experts Say

When first-grader Dean Pagan started having trouble with simple math problems and began earning “red” instead of “green” on his teacher’s behavior chart, his parents started to worry. The chart indicated he hadn’t been following directions. His parents took him to a psychiatrist and a therapist, and he was diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. But after his teacher spotted him putting a paint chip in his mouth during class, they had him tested for lead poisoning.

The results were devastating — the lead level in Dean’s blood was nine times as high as that known to cause permanent brain damage.

Dean’s own classroom had poisoned him.

He had been eating paint chips that fell onto his desk because he wanted to keep his workspace neat and because he wasn’t allowed to get out of his seat without permission during class.

In Dean’s school in Philadelphia — and in schools around the country — toxins like lead, asbestos, and mold are common. When buildings are left to age without good cleaning and prompt repairs, such toxins can be released into the spaces where children play, learn, and eat.

Any school built before the 1970s has “legacy toxics” like mold, asbestos, and lead, said Mary Filardo, executive director of the 21st Century School Fund, which advocates for school infrastructure improvements and modernization. But, she added, good cleaning and prompt repairs can keep kids safe. Asbestos isn’t a problem until floors, walls, and other parts of buildings are allowed to deteriorate, releasing poisonous asbestos fibers into the air. One way that can happen is if schools have problems with their heating and cooling systems, making the air too humid.

Without modernization and maintenance, the classrooms are “a much more hazardous place to be,” she told The 74.

The average school building in the United States is more than 40 years old, according to 2012-13 data, the most recent available, and experts say the federal government should be doing more to help states keep up with maintenance and repairs.

U.S. schools earned a grade of D+ on the American Society of Civil Engineers’ most recent “Infrastructure Report Card,” which noted that “the nation continues to underinvest in school facilities, leaving an estimated $38 billion annual gap” between actual spending and need.

Dean’s story came to light after a series of investigations by two Philadelphia newspapers revealed students were being exposed to dangerous levels of lead, asbestos, and other toxins. The investigations conducted by The Philadelphia Inquirer and the Philadelphia Daily News, with the help of school staff, found a pattern of neglect and ignored warnings on the part of the city’s schools.

Their investigations also revealed that lead paint was not the only infrastructure problem in schools, which according to a district spokesperson average more than 70 years old. Students at one elementary school, Lewis C. Cassidy Academics Plus, reported chilly classrooms without heat, burst pipes spilling water onto their backpacks, mice and rats in the bathrooms, and a cockroach crawling out of a milk carton, according to the Inquirer. After a maintenance crew was called to fix peeling paint and mold at A.S. Jenks Elementary, students were exposed to asbestos fibers from broken floor tiles and dust containing lead from disintegrating paint. At both schools, test results showed alarming levels of asbestos exposure, which can cause a range of health problems.

Lee Whack, the district’s spokesman, disputed some of the Inquirer’s findings, noting “faulty” methodology and the fact that staff members, not trained scientists, collected asbestos samples from the classrooms.

“We know that our students and staff deserve better school buildings,” Whack told The 74. “We understand that there are issues in our buildings, and we are actively working to address them.”

A system in crisis

In response to the investigations, the three congressmen who represent Philadelphia urged the House in May to allocate money to help the city repair its schools. The representatives — Democrats Bob Brady, Brendan Boyle, and Dwight Evans — asked House leaders to consider including money for Philadelphia schools in any infrastructure plan that comes before Congress.

But can districts like Philadelphia move forward without federal help?

The district assessed the condition of its school buildings last year and reported that the buildings need roughly $4.5 billion in repairs. But the news comes at a time of deeper fiscal woes for the district. Philadelphia’s City Council recently passed a budget that is projected to allocate an extra $617 million to schools over the next five years to help stabilize the system’s finances and stave off debt.

David Masur, executive director of PennEnvironment and an organizer of the Philly Healthy Schools Initiative, is focused on driving change locally. Currently, he and other members are pressing the Philadelphia City Council to pass legislation that would codify for schools best practices for lead paint removal and stabilization. He’s also focused on increasing accountability and transparency in the district’s communications with families and other stakeholders.

Masur said people are “lined up to help” the school system deal with the problems it’s facing, but some of the offers have been ignored by district leadership.

Whack, the district’s communications director, said the district is engaged in some partnerships already, including with the initiative, and is open to working with anyone who wants to help. Additionally, the district has recently adopted new cleaning standards for school buildings and is planning to do some lead removal this summer.

Filardo, the advocate for school facilities, said the federal government needs to allocate money to states to repair and rebuild schools. Repairing and modernizing the schools will also require a new level of cooperation in the city, bringing together the business community, the school district, and civic leaders, she said. That the city’s schools are still being used a century after they were built is a “tribute to their quality.”

“Where they are in Philly is not unfamiliar,” Filardo said. But to fix the problems, “It’s going to take a level of cooperation and planning that they have not seen yet in Philadelphia.”

In an opinion article for the Inquirer, Philadelphia schools superintendent William Hite said much the same thing: “We are facing a challenge that could seem too big to solve. It isn’t. But it will require an all-hands-on-deck effort from every neighborhood in this city.”

PennEnvironment’s Masur says there are more aggressive steps the school district can take right away — without community input or increased funding — such as communicating better with parents and using proven best practices to clean up lead, mold, and asbestos. The school district “exploits” the idea that it cannot do anything until it gets more funding because that is easy for people to understand, he said. His message, that the district can act now, is more difficult to explain.

“It’s harder to go, Look, what we’re saying here is a little nuanced: They do need more money, but there’s shit they could do today. Without money.”

Asbestos and other toxins remain in schools

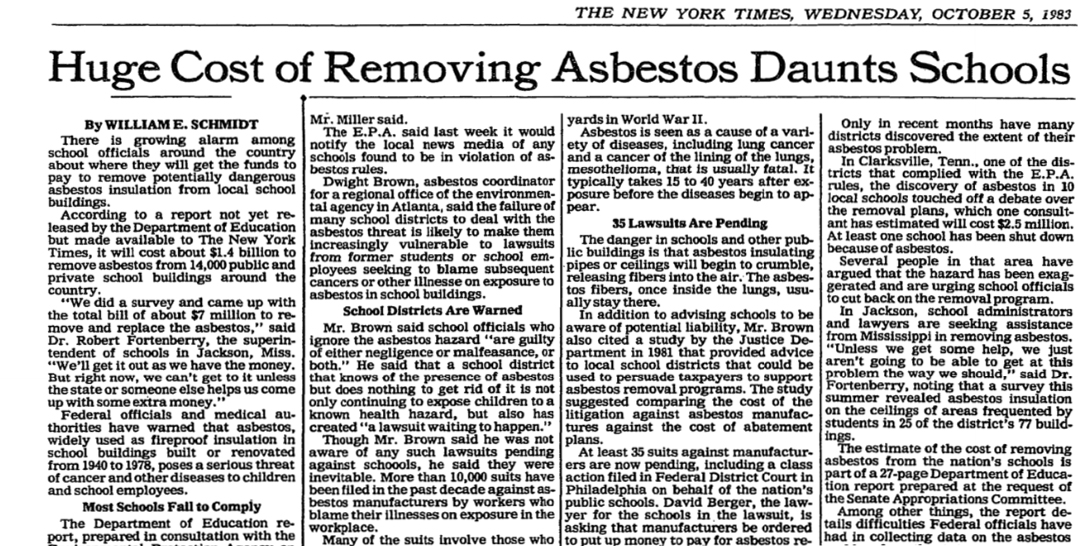

These issues are not new. A 1983 New York Times headline lamented that the “huge cost of removing asbestos daunts schools.” More than 30 years later, the work of removing asbestos from some schools remains undone.

Nearly 70 percent of school districts reported schools with asbestos in a 2015 survey conducted through the offices of Sens. Edward J. Markey and Barbara Boxer, with 20 states responding. The senators’ report also notes that “States do not appear to be systematically monitoring, investigating or addressing asbestos hazards in schools,” despite a 1986 law requiring them to do so.

A Politico/Harvard poll conducted in February revealed that a majority of Americans from both parties think improving school buildings is an “extremely or very important priority.” Filardo said she expects to see Congress tackle school infrastructure next year because voters are becoming aware of these issues and advocating for their schools. Earlier this year, advocates urged President Donald Trump to allocate funding for schools in an infrastructure package, but a tentative plan released by the White House did not mention schools.

“We actually think that in the 2019 Congress … [Lawmakers] will listen to voters on what’s important back in local communities,” she said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)