New Data Illustrate the Depth of America’s College Completion Crisis

This is the latest article in The 74’s ongoing ‘Big Picture’ series, bringing American education into sharper focus through new research and data. Go Deeper: See our full series.

American higher education is experiencing what some experts have called a “completion crisis.”

The proportion of high school graduates who immediately matriculate to college has risen substantially in recent decades, even as the high school graduation rate has itself climbed. But a dark trend has emerged alongside these cheery developments: Just 40 percent of the freshmen enrolled in four-year colleges each year graduate with a degree on time. Roughly one-third of all college students in both two- or four-year programs never earn a degree at all.

That adds up to almost 4 million college dropouts stuck with billions of dollars of debt for their troubles. And each year, the cycle perpetuates itself: from triumphant high school commencement speeches to tragic choices, sometimes just months apart, to financial burdens that haunt former students for years to come.

In searching for solutions, much of the scrutiny has fallen on colleges and universities. And indeed, institutions of higher education vary widely in the support they offer to low-income and minority students, who are the likeliest to encounter obstacles on the path to graduation. For every Bethel University or SUNY Alfred, where disadvantaged undergraduates attain degrees in numbers that defy the odds, there is a University of Nevada at Las Vegas, where students seem to struggle inexplicably.

But the numbers are no less stunning on the K-12 side. Simply put, the differences in college outcomes between relatively advantaged and disadvantaged high schools can be shocking. While colleges may not succeed at placing all of their students on the pathway to upward mobility, that’s partially because they are being asked to remedy social divisions that have been on the scene much longer than they have.

That’s the inescapable takeaway from a recent release of data by the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. The group’s seventh annual report on national college benchmarks — essentially tracking how many K-12 students enroll in, persist through and graduate from college — offers a bracing perspective on the inequalities that cleave American education.

Circulated in early October, the report compiles data from about 6 million students who have graduated from public or private high schools since 2012. Roughly 40 percent of all U.S. high school graduates are represented in each year tracked, the authors write, providing “the most relevant benchmarks that secondary education practitioners can use to evaluate and monitor progress in assisting students to make the transition from high school to college.”

The data yield a swath of noteworthy findings, but two major conclusions stand out.

Most students aren’t graduating on time

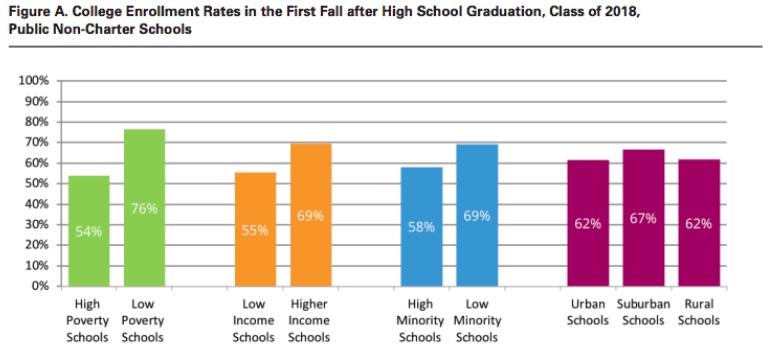

It won’t surprise many to learn that graduates from relatively advantaged high schools are more likely to enroll in college than those from relatively disadvantaged ones. NSC’s report demonstrates those disparities clearly: More than three-quarters of all graduates from low-poverty schools (defined as those where 25 percent of students or less are eligible for free or reduced-price lunch) immediately enroll, whereas just over half of those from high-poverty high schools (where 75 percent of students or more are eligible) do the same.

A similar distinction exists between schools on racial lines. Fully 69 percent of graduates from “low-minority” high schools (defined by the authors as those where 40 percent of students or fewer are black or Hispanic) enroll immediately in college, compared with just 58 percent from “high-minority” schools (those where over 40 percent of students are black or Hispanic). (Importantly, these figures increase across all school types when researchers include students who enroll during the spring or summer semesters.)

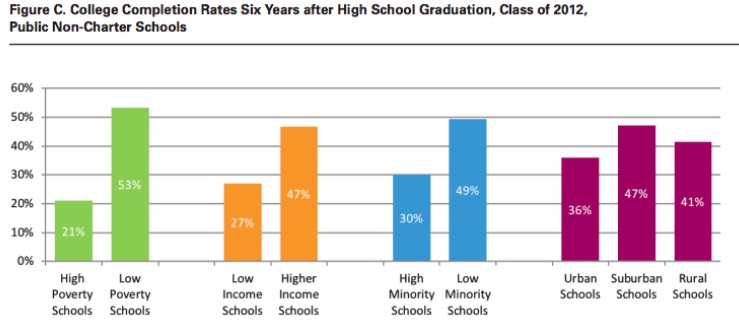

Those gaps are troubling enough. But they actually grow when the standard changes from immediate enrollment to eventual completion. Over half of all college students who matriculated from low-poverty schools graduate within six years of their enrollment, compared with just 21 percent of those who graduated from high-poverty schools. Forty-nine percent of graduates from low-minority schools complete a degree within six years, compared with 30 percent of graduates from high-minority schools.

The figures seem to offer a granular picture of how later-life educational inequities divide American adults. If students at predominantly non-white, nonaffluent schools are less likely to enroll in college — and less likely still to eventually graduate — it’s no wonder that just 11 percent of Hispanic adults possess bachelor’s degrees while 24 percent of whites do. Statistically, students from those demographics are also much more likely to default on college loans, often in spite of the fact that they qualify for federal aid like Pell Grants.

But as disturbing as the disparities are, so is the overall picture: Millions of American high school graduates, even those from relatively more advantaged backgrounds, are simply unable to graduate from college; even those who graduate often struggle to do so within a reasonable span of time. Delays of this kind lead to more debt and more dropouts.

Income may matter more than race

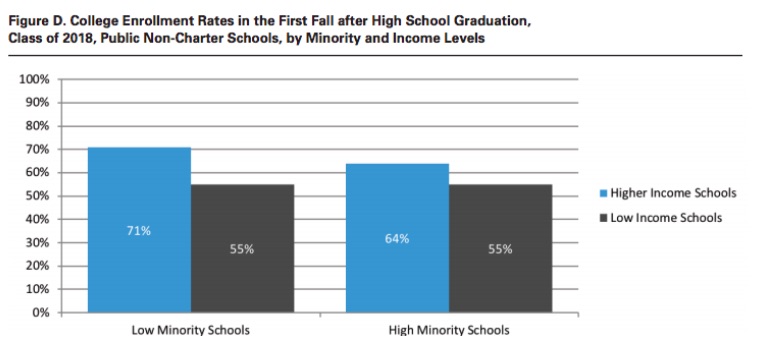

The second conclusion is even more striking. Among graduates from low-income high schools, the authors find, the proportion of students who enroll immediately in college is the same: 55 percent, whether those schools enroll relatively higher or lower percentages of minority students.

Among higher-income schools, graduates from those with smaller minority student populations are more likely to enroll in college right away, but not by a huge amount: 71 percent, compared with 64 percent from those schools designated “higher-income, high-minority.”

That would suggest that a student’s approximate chance of enrolling in college after high school is tied more closely to the socioeconomic composition of their high school than the racial makeup.

“The outcome differences between higher and low-income levels, within each minority level, were substantially larger than the outcome differences between high and low minority levels, within income,” the authors write.

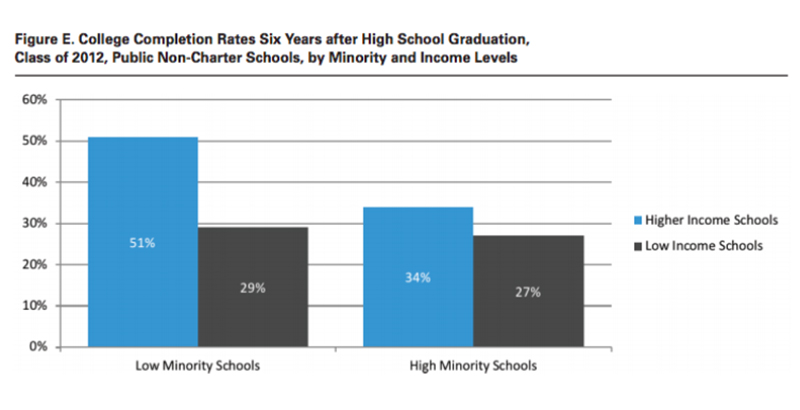

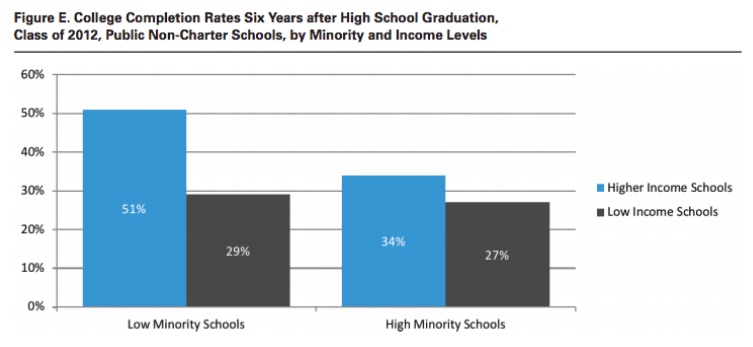

As one would expect, college completion rates are dramatically lower for all categories of schools than their enrollment rates. No population drops further in this respect than graduates from those high-income, high-minority schools: While nearly two-thirds of them enroll immediately in college after graduation, just over one-third finish college within six years. Less than 30 percent of graduates from low-income high schools — regardless of whether they enroll higher or lower percentages of minority students — finish college in six years.

Just one set of graduates has a better-than-even shot of attaining a college degree within six years of finishing high school: those from higher-income, low-minority high schools.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)