Massachusetts Study Finds That New Charters Boost Spending at Nearby District Schools — and Change How They Spend It

This is the latest article in The 74’s ongoing ‘Big Picture’ series, bringing American education into sharper focus through new research and data. Go Deeper: See our full series.

New charter school openings can change the way traditional schools spend their money, according to a new study circulated by the National Bureau of Economic Research. Massachusetts school districts that saw charter expansions also experienced temporary increases in per-pupil funding among traditional schools and shifted more dollars toward instructional spending and salaries over several years.

The authors attributed the somewhat counterintuitive result to the state’s policy of reimbursing traditional schools for the costs of students who transferred to charters.

Those findings are particularly noteworthy given the setting. Massachusetts debated the question of whether to lift its statewide cap on charters in 2016. Following a bitter and expensive campaign, the expansion measure was decisively rejected by voters. One key argument among those who supported retaining the cap was that new charters would divert resources from existing public schools.

The study was written by Camille Terrier, an economics professor at Switzerland’s University of Lausanne, and Matthew Ridley, a doctoral student at MIT’s School Effectiveness and Inequality Institute. Using data from the Census Bureau and the Massachusetts Student Information Management System, the researchers studied the impact of a 2011 funding reform that allowed low-performing districts in Massachusetts to devote more of their funding to charter schools. In districts that chose to pursue expansion, attendance at charter schools increased from an average of 7 percent of all public school students to 12 percent.

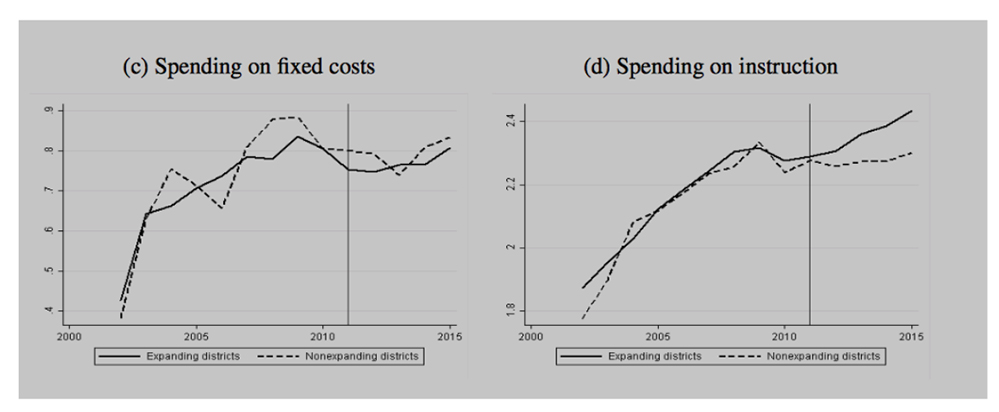

The results are noteworthy. While many skeptics fear that new charter schools siphon funding from nearby traditional schools, Terrier and Ridley find the opposite: “Higher charter attendance both increases per-pupil expenditures and shifts districts’ expenditures towards instruction and away from support services,” they write.

Specifically, in a series of mostly large, low-performing districts (Boston, Chelsea, Gill-Montague, Lawrence, Lynn, Malden, New Bedford, Salem, and Winchendon), per-pupil spending in local districts increased by 4.8 percent, even as many students transferred to new charter schools. Funds spent on instruction and salaries increased by 7.5 percent and 5.2 percent, respectively, while the portion spent on support services (school counselors, teacher training, and administration, among other costs) decreased by 4.4 percent.

Those general conclusions dovetail neatly with those of other recently published research. A study published last year by Temple University’s Sarah Cordes found that both student achievement and per-pupil expenditures jumped in New York City district schools after charters opened nearby — and the greater the proximity, the larger the effect.

The cause for the shift in resources toward instruction isn’t immediately apparent, Terrier and Ridley note. But charter advocates like Stanford economist Caroline Hoxby have postulated that school districts might respond to charter competition by directing funds away from fixed or administrative costs toward areas more commonly associated with student achievement, such as textbooks or higher teacher salaries, in an effort to compete for students.

That doesn’t fully explain why per-pupil expenditures increase in districts that are losing students to charter alternatives, however.

The answer to that question may lie in Massachusetts’s unique approach to charter school funding. Rather than simply reallocating the full education costs of each departing district student to their new charter schools, the state actually continues to pay a portion of that tuition to the district for several years — even though the student is long gone. For the first year after a student departs, the school he left still receives 100 percent of his per-pupil education costs. In each of the five subsequent years, the school receives 25 percent of those first-year costs.

Encompassing reimbursement for both instructional and facilities costs, the state disbursed roughly $80 million in total state aid for district schools affected by departing students during the 2016-17 school year.

As the reimbursement dollars peter out in the years following student transfers, the impact on school expenditures tapers off as well, though they never dip beneath the status quo before the charter expansion. “These results indicate that the refund scheme may be effectively insulating districts from the short-run financial shock due to expansion so that they can adjust in the long run,” the authors write.

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

;)