This is the latest article in The 74’s ongoing ‘Big Picture’ series, bringing American education into sharper focus through new research and data. Go Deeper: See our full series.

With the 65th anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education at hand, it’s a good time to reflect on the racial dynamics at work in American schools.

Here’s what we know: The United States is now more racially diverse than it has ever been, almost entirely because of a decades-long surge in the number of Hispanic students across the country. Yet according to many experts, our schools don’t reflect that diversity. Indeed, by some measures, black and white students are now as segregated from one another as they have been at any time since the 1960s. (I wrote about these startling numbers in greater depth prior to the anniversary: “Will Schools EVER Be Integrated?”)

So what’s really going on here?

To find the answer, we need to check out some charts:

1 American neighborhoods are getting more diverse.

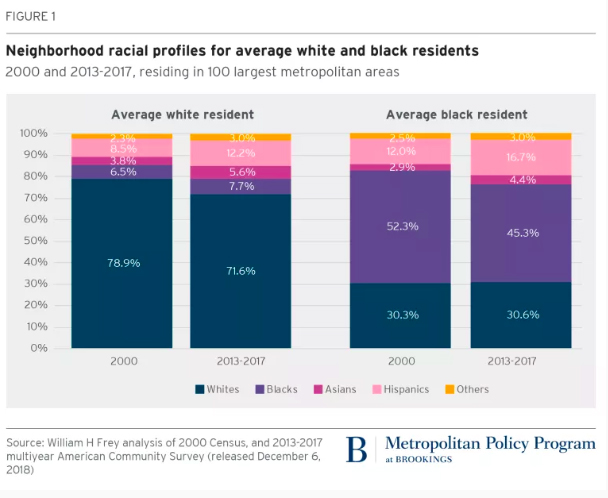

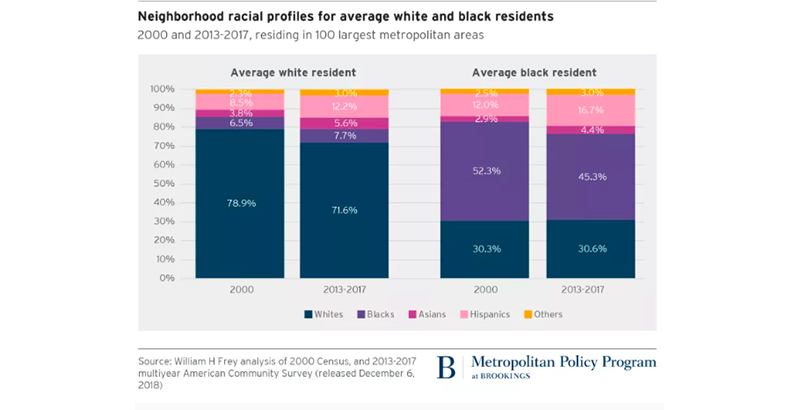

Happily, research shows that levels of racial segregation in neighborhoods have declined steadily over the past half-century. That welcome development can be traced to a few different trends.

Most notably, the nation’s Hispanic population has simply exploded since the time of Brown v. Board, with Hispanics supplanting blacks as the nation’s largest minority group (the numbers of Asian Americans have also risen quickly). At the same time, the formerly adamantine barriers between black urban centers and white suburbs have loosened dramatically, as educated and affluent whites have poured into cities at the same time black families have migrated out of them.

In recent decades, demographer William Frey has found, segregation has declined in 93 out of America’s 100 largest metropolitan areas. While black and white populations are still ultra-isolated in a few Northern and Midwestern cities (New York, Milwaukee, Detroit and Cleveland principal among them), they have melded to a substantial degree in Sun Belt communities like Las Vegas, Phoenix and San Antonio.

2 Whites are shrinking as a percentage of the student population.

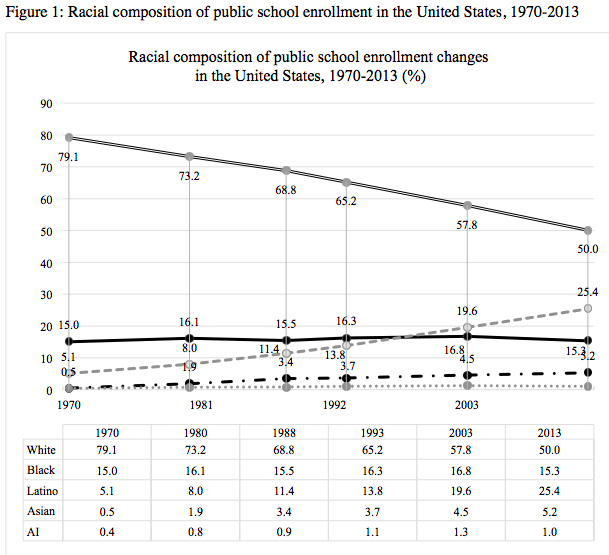

The population’s gradual tilt away from whiteness is most pronounced among young people. By some estimates, the K-12 student population is already minority-majority; that completes a long slide in the number of white students as a percentage of America’s entire student body.

Between 1970 and 2013, as immigration from Latin America and Asia took off, whites declined from nearly 80 percent of all public school students to just 50 percent. The percentage of black students has stayed almost identical over that time, while Hispanics have come to account for one-quarter of the student population as a whole.

3 Black and white students see less of one another.

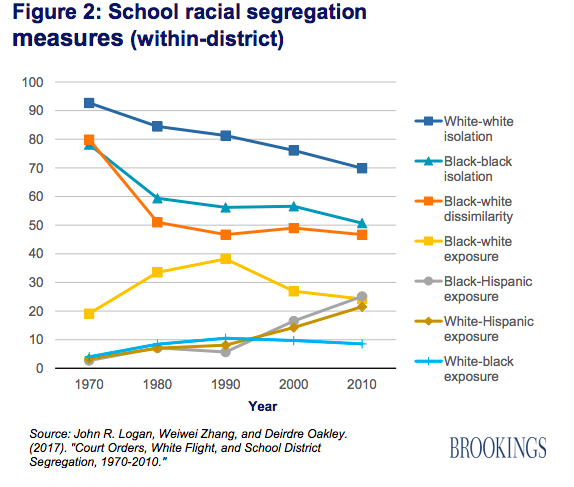

After Brown (well, really after 1970 or so; resistance to integration was so strong that very little progress was made until 15 years after the decision was issued), it became much more common for black students to encounter white classmates at their schools. Between 1970 and 1990, the rate of black-white exposure — i.e., the rate at which the average black student saw white students at his school — roughly doubled.

But the trend began to reverse itself over the past few decades. Now, according to some experts, Brown’s initial successes in bringing black and white students together have been largely forfeited. On the bright side, white-Hispanic and black-Hispanic exposure have both ticked steadily upward over the same period.

4 Districts aren’t looking over their shoulders anymore.

According to some social scientists, there’s a clear link between the shifting racial composition of American students and the precipitous drop in exposure between black and white students. A smaller portion of white students overall means fewer will encounter black students at their schools. Their places have been taken by Hispanic and Asian students through largely race-neutral processes, it is argued.

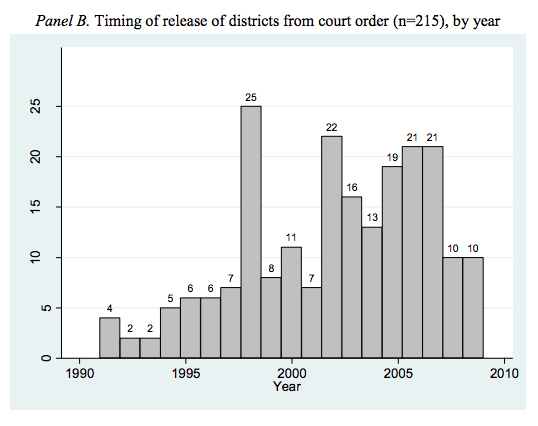

But other forces have been at work at the same time. Beginning in 1991, after the Supreme Court’s landmark Dowell v. Oklahoma City ruling, school districts began to be released from court-ordered desegregation plans. Hundreds of major city districts have now voided the orders, which were mandated in the wake of Brown to force them to integrate public schools. That’s led to a wide-scale resegregation ever since, according to Gary Orfield, head of UCLA’s Civil Rights Project.

Go Deeper: This is the latest article in The 74’s ongoing ‘Big Picture’ series, bringing American education into sharper focus through new research and data. Go Deeper: See our full series.

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

;)