From a Rural Village to the University of Alaska: How the First Female Native Engineering Professor Stresses Value of ‘Belonging’ for Young STEM Enthusiasts

For as long as she can remember, people have been telling Michele Yatchmeneff that she wouldn’t succeed.

When she wanted to take high-level math and science courses in high school, some people advised her against it. The discrimination — because she was a girl and an Alaska Native — would continue long beyond high school. Even years later, while earning her doctorate at Purdue University, some people still treated her like a “minority quota.”

“I had a student ask me where I was from, and you could tell he didn’t think I was at his level because I hadn’t gone to a fancy school before going to Purdue,” she said. She remembers having the sense that the other student walked away from the conversation thinking that she received a fellowship and a place at the school because “you’re female and …because you’re Native, so you’re meeting a quota that they have here at the university.”

Yatchmeneff went on to become the University of Alaska’s first female Native engineering professor in 2015. She is dedicating her research to giving back to her community, offering encouragement to young Native STEM enthusiasts and a sense of “belonging” she was often denied. She was recently awarded a $500,000 research grant from the National Science Foundation to identify the characteristics Alaska Native high school students associate with belonging and how those characteristics influence their decisions to pursue higher-level math and science classes. She defines belonging as a classroom atmosphere in which students feel “whole” and confident being themselves. Her goal is to share that information with teachers through professional development in order to help them guide Alaska Native students to success in STEM education and careers.

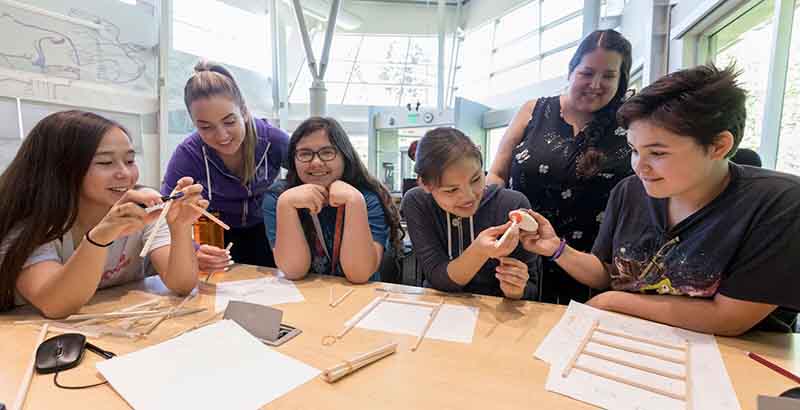

Yatchmeneff and one of her colleagues were the first Alaska Native faculty to join the engineering department at the University of Alaska Anchorage. In addition to being a researcher and professor, Yatchmeneff helps with residential science camps that introduce Alaska Native students to STEM and the University of Alaska Anchorage campus.

Humble Beginnings

The journey to teaching engineering at the Anchorage campus began when she was young girl living with her family in subsistence villages on Alaska’s Aleutian chain, where they hunted, fished and gathered berries to survive.

She attended school in Anchorage, which offered good math and science classes, she remembers. But she didn’t always find encouragement from her teachers.

“You could just tell they didn’t think I was going to be successful, so they were kind of discouraging me,” she said. Even then, her reaction was to just keep going: “You have to just kind of not listen to that and just persist.”

Some teachers did recognize her abilities. Yatchmeneff first encountered engineering when her high school chemistry teacher encouraged her to attend an introduction to engineering camp in Denver.

“He actually handed me the application and said, ‘You should probably go to this,’” Yatchmeneff remembers. She had already been taking difficult math and science classes, but at the camp, she learned engineering was more than just “the guy on the train blowing the whistle.”

“Then I was hooked,” she said, and she started applying to engineering schools when she got home.

But it was often a tough road. When she talks about responding to doubters throughout her life, such as the man at Purdue, Yatchmeneff is matter-of-fact: “I just ignored it.” she said. “I got all A’s in all of my courses, and I made it through in three years where most people take four and five years to make it through. … Once they realized I meant business, and … I was there to get through this and get back to Alaska, they realized, ‘OK, she belongs here.’”

It was at Purdue that Yatchmeneff started researching what motivates Alaska Native students to persist in STEM education and careers. She found that having a sense of belonging was crucial. Now, as an engineer, professor, and mentor, she’s working to make sure no student feels the way she did.

Breaking barriers

Although she has won three National Science Foundation grants, earned advanced degrees in engineering, and broken numerous barriers for Alaska Native women in science, Yatchmeneff gives credit to the support she’s received from the Alaska Native Science and Engineering Program (ANSEP), which she first encountered as an undergraduate. The organization works to improve education and employment opportunities for Alaska Native students and professionals.

Today, the organization offers programs for students from middle school to the doctorate level, providing education, mentoring, networking opportunities, and scholarships.

“I definitely would not be where I am today without the support of ANSEP,” she said. It was always a comfort, she added, knowing there was someone there, “regardless that I was female, regardless that I was Alaska Native,” who “had the confidence that I was going to be successful and gave me the tools to do that.”

Asked how she mentors younger students who look up to her, Yatchmeneff said she encourages them to persevere in their science classes, shares her story with them and helps them find internships. She also reminds them that at ANSEP, they will always belong.

“ANSEP is a really big family, and we have all these people here that are going to back you up,” she said.

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

;)