Challenging Conventional Wisdom, Report Finds Promising Academic Performance in Chicago’s Growing English Learner Population

This is the latest article in The 74’s ongoing ‘Big Picture’ series, bringing American education into sharper focus through new research and data. Go Deeper: See our full series.

For years, the academic performance of English learners in Chicago has looked grim, with research showing they lag far behind students who entered school as native English speakers. But a new report calls into question that conventional wisdom.

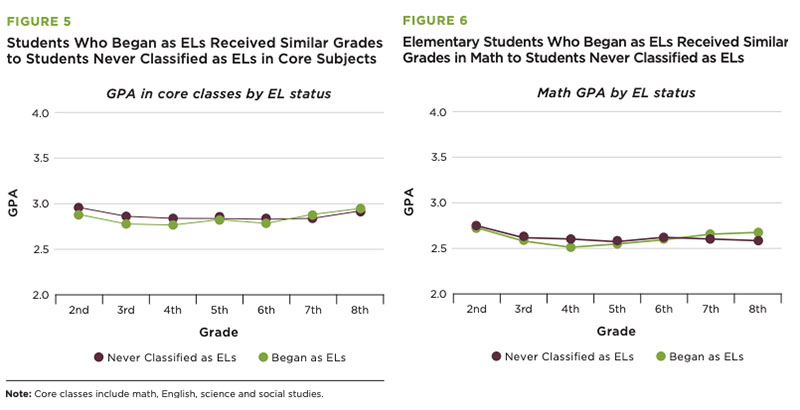

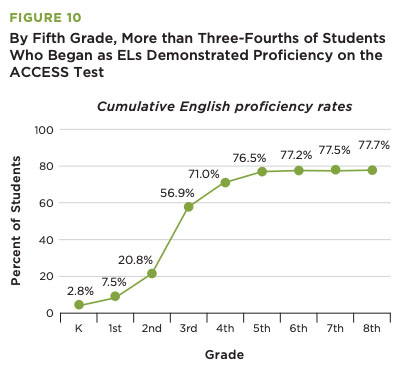

By eighth grade, most Chicago students who began their first year of school unable to speak English fluently had academic achievement similar to — or even better than — their native-English classmates, according to the new report by the University of Chicago Consortium on School Research. More than three-quarters of the children in the study were proficient in English by eighth grade. These students, researchers found, had better attendance, math scores and overall course grades than their native-English peers. Meanwhile, the two groups had similar test scores in reading.

A bilingual education program at Chicago Public Schools may have played a role in the promising results. But another factor could be at work: Researchers used what they say is a more accurate way to assess student performance.

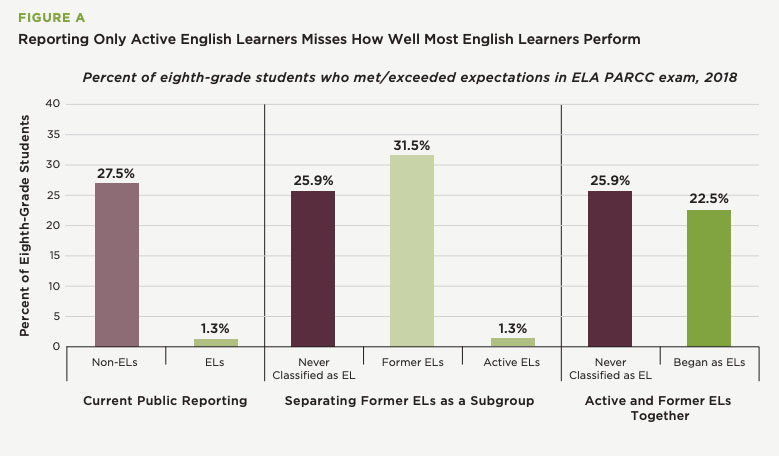

Research and school accountability data often focus on “active English learners” who have not yet reached proficiency in the language. When students become proficient, they leave the English learner category and their progress is measured only as part of the general student population. That strategy therefore provides a “biased picture” of English learners’ academic performance, according to the report.

“That was actually a little bit troubling to us because it doesn’t really paint the whole picture of what our schools are doing” to improve the performance of English learners, said report co-author Marisa de la Torre, senior research associate and managing director at the consortium.

Consortium researchers tracked 18,000 Chicago students and analyzed the long-term trajectories of children who began kindergarten as English learners through eighth grade. Their performance was then compared to Chicago students who were never classified as English learners. The positive findings suggest the instruction given to Chicago’s English learners is academically appropriate.

The report comes as the number of English learners in Chicago and elsewhere has grown exponentially. In schools across the country, the proportion of students who are English learners grew by 26 percent between 2000 and 2015, according to federal education data. During the 2018-19 school year, about a quarter of Chicago’s public school kindergartners were not fluent in English. Districtwide, about one-third of Chicago students are classified as English learners at some point in their academic careers.

With that population growing, the report demonstrates that the district’s strategies are working, said LaTanya McDade, the district’s chief education officer. The district, America’s third-largest, has more than doubled the number of campuses with dual language programs since 2016. These programs offer students course instruction in both English and their native language. Meanwhile, the district has hired an additional 1,000 bilingual educators since 2015, according to district data.

The district’s focus on biliteracy, McDade said, gives students a competitive edge. “We see biliteracy as their superpower,” she said, so “we want to make sure that we are, yes, immersing students in English, but also in their native language.”

A potential notch in the district’s favor is that while some states prioritize English-only education, schools in Illinois are required to offer transitional bilingual or dual language programs. It’s possible that the district’s emphasis on dual language programs builds “on the strength of students’ home language and culture, rather than seeing them as impediments,” according to the report.

While much of the research on English learners centers on children in California, the report’s focus on Chicago students is notable because Illinois law requiring bilingual education and funding for such programs has been consistent over time, said Rebecca Vonderlack-Navarro, manager of education policy and research at the Latino Policy Forum.

“California has been all over the place when it comes to bilingual education; they were English-only for a while,” Vonderlack-Navarro said during a press conference in Chicago last week. “We need to maintain investment in [English learner] programming because it works.”

De la Torre called the report’s findings on student attendance especially notable. For low-income students, factors such as unreliable transportation or inadequate health care can prevent them from showing up to school. But the research found that Chicago’s English learners “were actually coming to school much more often” than their native-English peers, even though they’re more likely to be economically disadvantaged, she said. It remains unclear to what extent district policies contributed to English learners’ academic performance, de la Torre said. But she’d like to see similar analyses in other districts to understand how the achievement of English learners elsewhere resembles the results in Chicago.

Despite overall promising results, however, the report did find a significant share of English learners in Chicago who struggled to learn English.

More than half of the students in the study were English proficient by third grade, as were three-quarters by the end of fifth grade. But students who didn’t reach proficiency by that point — typically male and identified for special education — were unlikely to do so by high school, researchers found.

The 1 in 5 students who didn’t reach English proficiency by the end of eighth grade also struggled in school more broadly, according to the report, and had lower attendance, grades and test scores than those who learned the language earlier on. But there is a silver lining: Scores on the first-grade English proficiency test showed a clear gap between students who eventually became proficient in the language by high school and those who did not. That finding suggests that educators may be able to identify these students early in their schooling and target them with more intensive services. McDade said the district is currently exploring ways to implement early intervention services for students who struggle to demonstrate English proficiency.

Meanwhile, in Chicago and beyond, it’s important for policymakers to track the performance of English learners over the long term, Vonderlack-Navarro said.

“For too long under No Child Left Behind, we looked at how a child did at one point in time on an exam and made so many assumptions,” she said. “Now we’re learning it’s not the kids that were the problem. It was the adults and how we were looking at the data.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)