Boston Massively Expanded Its Charter Sector — Without Sacrificing School Quality. New Research Sheds Light on How Education Reforms Can Remain Effective While Applied at Scale

How do you bring success to scale?

It’s a question that has tormented education experts — and, really, anyone designing public policy — for years. Smart, successful investments in teacher coaching, whole-school reforms and new curricula have attracted rapturous headlines and public interest, then faltered after being brought to more classrooms. When education reforms are implemented in new contexts, by teachers and school leaders who played no role in creating them, their effects fade all too often.

But new research offers evidence that ambitious new policies can remain effective while applied at scale. The working paper, released earlier this month by the National Bureau of Economic Research, finds that charter schools in Boston kept hitting high marks even after replicating their model several times over. The city’s charter sector, ranked among the best for systems across the country, saw no decline in its results.

First circulated by MIT’s School Effectiveness and Inequality Initiative, the study examined a period of rapid charter expansion in Boston between 2010 and 2015, when the sector roughly doubled in size. Co-author Christopher Walters, an economics professor at University of California, Berkeley, said he wouldn’t have predicted that the expansion would be so successful.

“The effect sizes that we see in these lottery comparisons are some of the larger effects you see anywhere in education policy research,” Walters said. “I expected that the schools would probably produce gains as they expanded, but the fact that they remained just as effective was certainly a surprise to me.”

Those effects were indeed substantial. By the researchers’ calculations, attending a charter school in Boston substantially improved students’ scores in both English and math.

The study covered the years following 2010, when Massachusetts lawmakers lifted a statewide limit on the percentage of education funding that could go to charters. The law was directed specifically at lowest-performing school districts like Boston. As a result, funding for charter schools grew to 18 percent from 9 percent of district funding in those areas, and operators filed dozens of applications for new charter schools.

Of note, the state limited the charter expansion to “proven providers”: existing charter schools whose students had already shown progress. Those schools — identified on the basis of both academic metrics (test scores, high school graduation rates and suspensions) and student data (high-need student populations, as well as student attrition over time) — accounted for four out of Boston’s seven charter middle schools. They would be allowed to expand their existing schools and establish new campuses.

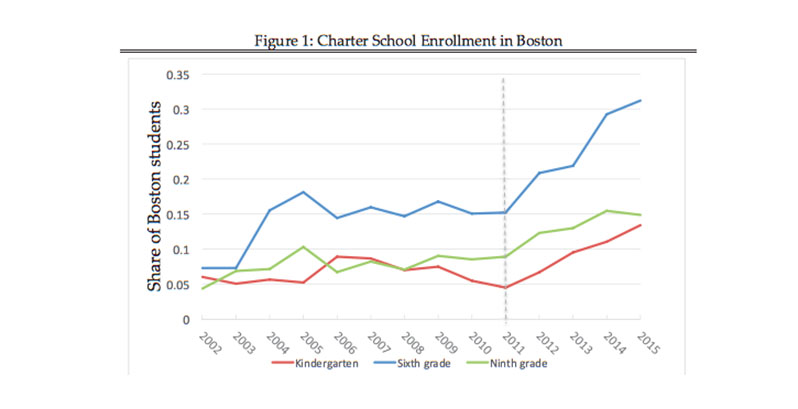

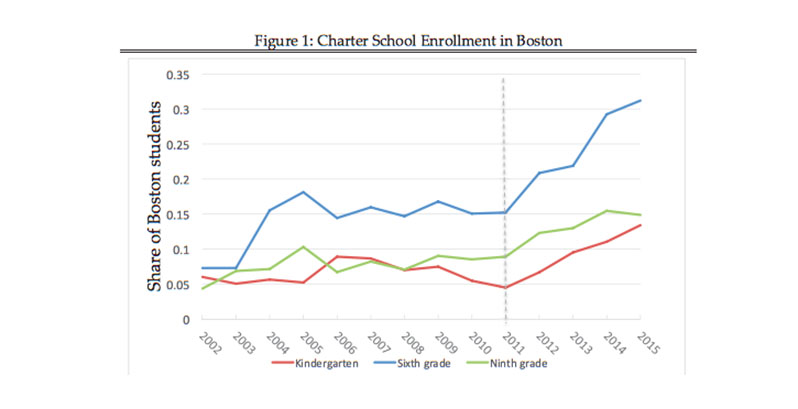

Expansion moved swiftly. Between 2010 and 2015, the percentage of Boston kindergartners enrolled in a charter school rose to 9 percent from 5 percent; sixth-graders enrolled in a Boston charter more than doubled in proportion — growing to 31 percent from 15 percent; and ninth-graders enrolled in a charter climbed to 15 percent from a previous 9 percent.

More importantly, academic data show that those students performed better than they would have elsewhere. The authors found that the charter schools selected for expansion produced larger learning gains over those five years than other charter schools. New and expanded charters posted similar academic results as their original campuses. And the proven providers saw no decline in quality, even as they directed existing staff and resources toward expanding operations.

Co-author Sarah Cohodes, a professor of education and economics at Columbia University’s Teachers College, suggested that part of the expansion’s success lay in the fact that Massachusetts had simply chosen the right charter schools to scale. While education leaders always try to pick good candidates for growth, the proven-provider strategy offered a “very promising path forward,” she said.

“Of course, all states and authorizing entities do have processes through which they decide who to authorize — they’re not just willy-nilly saying anyone can do it,” Cohodes said. “But they’re not necessarily focused on operators who have demonstrated success in other schools.”

Some charter advocates disagree. By requiring evidence of prior success, the conservative Pioneer Institute has argued, Massachusetts is deliberately slowing the growth of a resoundingly successful charter school sector. Others lament that if regulators favor charter models that have already succeeded, students will miss out on promising but unproven new practices.

At present, it’s difficult to picture any Massachusetts charters being asked to expand, whether due to their successes or public demand. A 2016 effort to further lift the statewide cap on charters was decisively defeated at the ballot box, and polls indicate that public support for the schools has waned significantly among Democrats, who make up the majority of Massachusetts voters.

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

;)