Williams: Replacing Mayoral Control With Elected School Boards is Not the Best Way to Shore Up Our Fragile Democracy — Or Run Schools

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

For years, a number of researchers and analysts — myself included — have been sounding the alarm that American democracy is facing a foundational crisis. If this warning seemed overanxious in 2016 (or 2011, or 2000), it’s now ubiquitous.

From top to bottom, our governing institutions have been significantly eroded by conservative assaults on the legitimacy of our elections, the growing influence of shadowy political front groups in electoral politics, conservative attacks on voting rights, opportunistic partisan abandonment of governing norms, sclerotic legislative processes, polarization fed by the culture wars and a bevy of other worrying trends.

The depth and breadth of the problem are most visible at the elemental level, where the American democratic spirit is ostensibly most fervent: our thousands of school boards. These little local legislatures have been revered as cornerstones of American democracy since at least the early 19th century. In theory, they provide local schools with democratically elected leadership that is maximally responsive to local needs and the public interest.

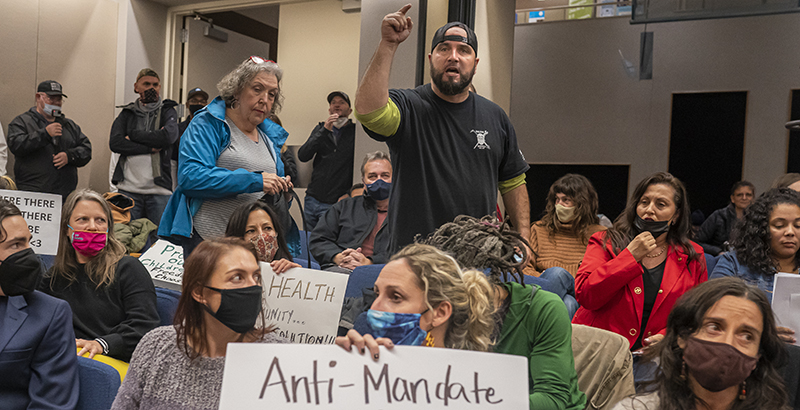

And yet, the pandemic has brought months of news cycles where local school board debates have escalated into screaming matches complete with threats of violence over issues both imaginary (e.g. the supposed rise of critical race theory in U.S. classrooms) and/or conspiratorial (e.g. fights over mask or vaccine mandates). Things have gotten so bad that the National School Boards Association recently sounded the alarm, asking for the federal government to do more to protect elected local leaders from threats of violence. Rather than calming the waters, this just prompted further outrage — particularly from conservative politicians in Washington, D.C. who cast it as an assault on parents’ free speech — and eventual backpedaling from the NSBA.

Problems like these are why, in recent decades, some major cities — places like Washington, D.C., Chicago, Boston, and New York City — moved away from elected school boards. The idea had a three-part theory of action: 1) it makes school governance more coherent by unifying control of city schools under mayoral leadership, 2) it insulates education decision-makers from political pressure and 3) it gives mayors a reason to prioritize school funding and improvement.

The returns from this experiment have been largely encouraging. According to Stanford University researcher Sean Reardon, Chicago schools are “dramatically outperforming not just the other big poor districts, but almost every district in the country, at scale.” Research on public schools in D.C. — including a recent Mathematica study — has also found significant improvements.

And yet, recently, the mayoral control model in these cities has faced criticism from a cacophony of voices claiming that returning public education to school board control would restore an elemental part of U.S. democracy — representative government at its most profoundly local level.

As the country wrestles with a national crisis of democracy, it seems odd to focus outrage and energy towards shifting local school governance from the control of elected mayors to elected school boards — precisely at a moment when school boards across the country are providing daily proof of their weaknesses as institutions.

Aside from the novelty of conservative groups converting local protests into a coordinated national effort to inflame board meetings, there is nothing particularly exceptional about this latest spate of outrage. Remember the furor a few years ago over how the Common Core State Standards were ostensibly going to push schools to conduct mass retinal scans, promote student promiscuity and advance the cause of global communism? Sure, school board meetings are often sleepy for months — even years — but whether it’s school boundary changes or sex ed or school closures or school diversity or hiring and firing, periodic eruptions of dysfunction are pretty much a given.

And those are just recent examples. School boards’ institutional failures have deep historical roots. School boards have long been complicit, for instance, at designing and maintaining racist, inequitable structures in public education — including decades of segregated schooling. Who did Oliver Brown and his fellow plaintiffs have to sue to begin the long, slow, difficult, haphazard work of integrating American schools? Topeka’s Board of Education. It was the same in Washington, D.C., where Spottswood Thomas Bolling sued the president of the local school board over segregation in the District’s schools. Indeed, over and over again, the fight for integration required (and still regularly requires) confronting — and appealing to a higher authority over — local school boards.

It’s a reliable rule of education politics: elected school boards are almost always most responsive to vested and/or privileged interests in their communities. Consider, for instance, the Los Angeles Unified School District. For most of the last decade, their school board has faced criticism from experts, lawsuits from community groups, and pressure from the state to focus more resources on historically marginalized communities. And yet, nonetheless, the board has defaulted to allocating resources away from those communities. School boards simply aren’t designed to prioritize the less powerful, organized and noisy.

So … why, in light of significant educational progress in places that have experimented with other forms of school governance, is it suddenly so important to shift more power to local school boards? Notably, pushes in this direction in Chicago and Washington, D.C. have sparked as these cities’ black residents are increasingly being displaced. In D.C., at least, a move away from mayoral control would almost assuredly strengthen the voices of white, privileged voters — who would have a better chance of swaying the outcomes of a handful of low-turnout, ward-by-ward school board elections than the citywide mayoral race.

Indeed, what constitutes a democracy? Can it really be reduced to whether the public elects a mayor or a board to run the schools? Of course not. Institutionally speaking, modern democratic governance requires choosing leaders through regular, free, and fair elections … but it also requires the expertise of civil servants and other experts chosen by those leaders. That’s why, for instance, we don’t hold a national referendum every time the Mine Safety and Health Administration wants to adjust its regulations, nor do we establish elected panels to determine how much radium is safe to drink in our water supply.

So: you should absolutely be concerned about the state of U.S. democracy. It cannot long sustain when voting rights are selectively narrowed to grant partisan advantage, or when bills with majority support in both houses of Congress are regularly filibustered dead, or when sitting lawmakers resist efforts to fully investigate a violent attack on the U.S. Capitol.

But if you’re looking for a way to ensure that our schools have elected leadership that’s fair, equitable and democratically accountable, school boards pretty obviously aren’t the way to go.

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

;)