Williams: Charter Schools Hurt Their Cause When They Are Lumped In With Other Forms of School Choice

As election season heats up in our angry, polarized country, K–12 public education has attracted quite a bit more airtime than usual. Candidates running for anything from president to dogcatcher have found themselves obligated to articulate plans — however vague — for K-12 reform.

Many of these plans have focused inordinately on charter schools — free, publicly funded schools that are usually run by nonprofit organizations that enroll students through non-selective lotteries. In the 2016 school year, charters served around 6 percent of American students, but they still occupy a much larger share of national K-12 education politics.

Education reformers, who have generally narrowed the scope of their ambitions to defending charter schools, have been largely frustrated by this political moment. Many have responded by pushing their customary rhetorical defenses of charter schools, to little success. That is, reformers often defend these schools as one of many policy mechanisms for giving low-income families more options than the ones they can afford to purchase through the housing market. This is an instinctive move for charter advocates, who tend to see that kind of neighborhood school choice as a fundamental problem for equity in public education. Unfortunately, it also imposes political costs.

On the whole, activists, journalists, advocates and voters are not compelled by the old framings. After years as political darlings, charters have suddenly become political footballs. What’s going on?

To an important degree, it’s because they’ve elected to garb themselves with the language and — above all — the baggage of the so-called “school choice movement.” This is more true now than ever, given that President Trump’s new budget proposal would cut federal charter schools funding — partly to fund a new school vouchers tax credit. Whatever the past political reasons for this move, it’s clear that charter schools benefit less than ever from being grouped in a coalition with other choice programs.

First, voters are generally less supportive of the rest of the slate of school choice policy ideas: things like vouchers, for-profit and/or virtual charter schools, education savings accounts and tax-credit scholarships. In general, charters lose more than they gain by aligning with these unpopular ideas.

Second, this alignment invites challenging empirical problems into K-12 education reform politics. While studies generally suggest that well-regulated charter schools can advance achievement for students from historically disenfranchised communities, the data on other forms of school choice are not as encouraging. Indeed, although nonprofit charter schools in many places help these students succeed, the opposite is true for for-profit and/or online charter schools. The results from voucher programs have been weak.

Put simply, charters are more likely to provide quality academic opportunities for their students, while other forms of school choice are less likely. But this data point is easy to miss when charter advocates do not specifically distinguish between nonprofit charters and other, less-effective forms of school choice.

This hints at a third, related concern for charters. Advocates argue that these schools can empower educators who want to experiment with educational models that aren’t currently available in their districts (dual language immersion, Montessori, expeditionary learning, a classical liberal arts curriculum and so on). But these sorts of arguments are hard to square with large, visible evidence of for-profit companies running publicly subsidized schools that are neither unique nor better than traditional school districts.

They’re hard to believe when voters have seen online charter schools squirming to avoid accountability for their performance (and/or outright corruption). They’re not especially compelling when the public has learned to think of charter schools as substantively identical to expensive, low-accountability voucher programs that don’t serve students well.

The challenge, at base, is that different school choice programs are actually designed for a wide range of purposes. Neighborhood school choice is designed for geographical convenience and financial predictability — if you buy a house, you also buy access to the school assigned to serve it. Vouchers are designed to maximize parent empowerment by converting public education into a private “market” of educational “consumption.” And so forth.

Nonprofit charter schools have a different goal. They generally aim to free families from the inequitable economic hurdles in neighborhood school choice while also — crucially — building a curated slate of high-quality public school options. Those options are, in a working charter sector, held accountable for their academic performance over time. Charter school authorizers monitor schools’ results and close those that aren’t serving students well.

In other words, nonprofit charters have less in common with other forms of school choice than their opponents and advocates believe. To that end, they ought to divorce themselves from other forms of school choice. It’s time for them to embrace a message that tracks their unique advantages as public schools: Charters are public, accountable, effective school options that drive equitable opportunities for historically underserved communities.

This rhetorical shift will carry concrete consequences. While he was still in the presidential race, Sen. Cory Booker, one of the only Democratic hopefuls to speak positively of charter schools, put forth his K-12 education proposal that called for holding charters “to the same performance and transparency standards, including open meetings and records, as other public schools.” Charters should absolutely embrace this as a principle, especially if each increase in transparency and accountability comes with commensurate resources to increase their capacity to comply. Charters’ success derives from accepting accountability for improving student outcomes in exchange for the freedom to choose their own staff, curricula and schedule. Greater public transparency around board meetings and fiscal health shouldn’t meaningfully threaten any of those.

What’s more, insofar as charters are adopting more of the features of traditional public schools, policymakers should consider aligning traditional public schools with some aspects of the charter model. Charter leaders who welcome additional oversight should use the opportunity to encourage traditional public schools and their districts to accept the same levels of accountability that charters face around raising student outcomes. Charter schools are generally held accountable for raising student performance and risk closure if they fail to do so.

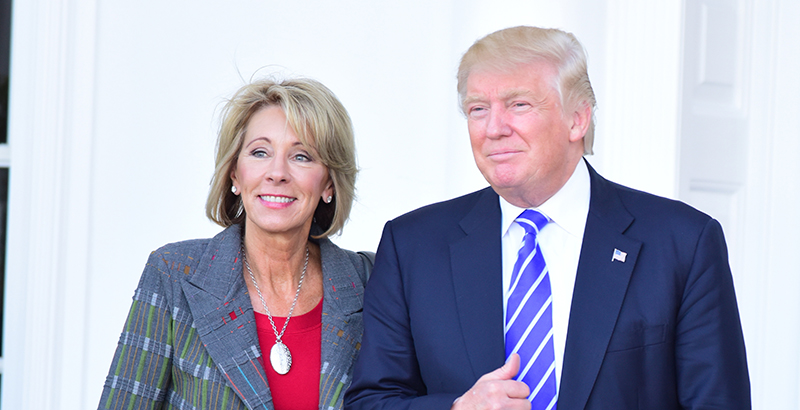

What do charter leaders, advocates and families have to lose? The extra weight of Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos’s unpopularity? The approval of tax-credit scholarship activists? One thing’s sure: Charters’ current strategy isn’t working, and without a course correction, they’ll be the losers in a whole lot of elections.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)