Williams: A New — and Long Past Due — Roadmap for Overhauling How Schools Serve English Learners

Ever talked to a precocious elementary schooler? Then you know all about collective nouns. What do you call more than one dog? A pack! A group of cattle? A herd! And, of course, sheep hang in flocks, fish swim in schools, and — best of all — those noisy birds on the roof are a murder of crows.

Get together a bunch of policy researchers, though, and what do you have? It’s one of the less well-known ones. When we gather, we’re a “fracas” of policy wonks. Not an ounce of cohesion in the bunch. This is most fully true at the most focused levels: the more specific the topic, the more fractious the fracas.

It’s certainly the case in my field, English learner policy, where years of serious research and debate have not yielded anything recently like a coherent manifesto or policy agenda to guide federal education leaders. Our work is too often vague and detached from English learners’ real needs.

To that end, I spent much of the past year sharing a short draft of policy recommendations with more than 100 folks who know and care about English learners’ success — educators, researchers and advocates — to collect feedback and develop a slate of concrete reforms to significantly improve how the country and its schools serve these students. The result, A New Federal Equity Agenda for Dual Language Learners and English Learners, was published at The Century Foundation today. It provides a much-needed starting point for overhauling the Every Student Succeeds Act and other federal policies governing English learners’ education.

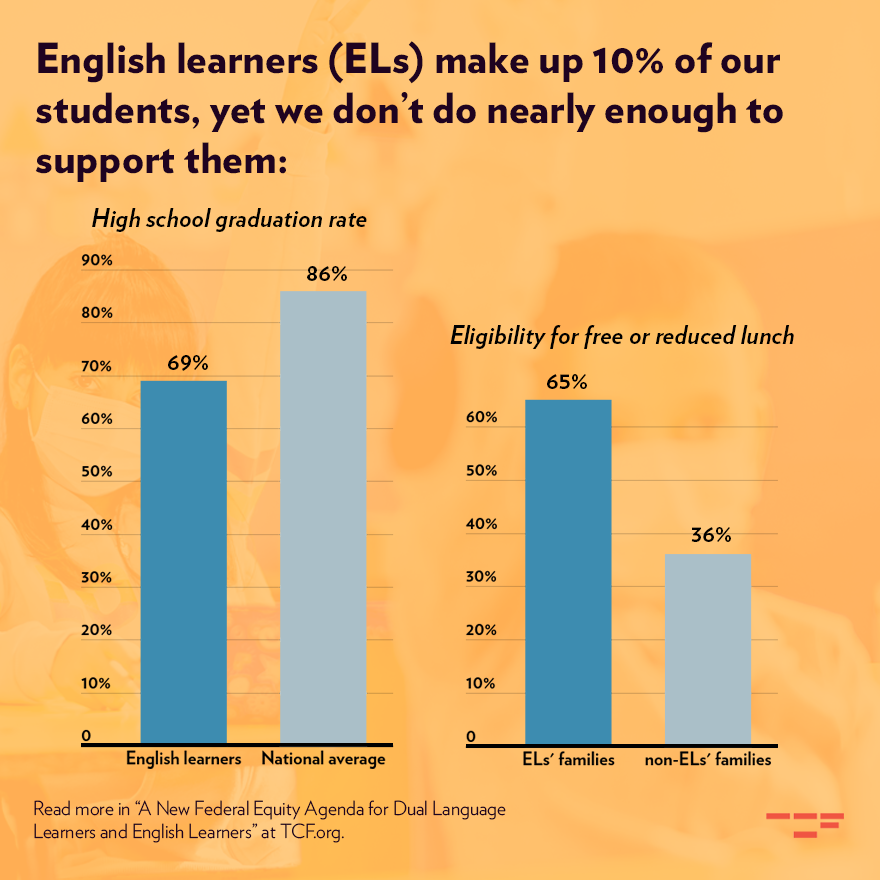

Above all, the report calls for a significant expansion in federal English learner investments. In the field of education policy, it’s not exactly fashionable to be direct about this. Policy wonks generally earn their way in this work by creatively reimagining existing systems, not simple, direct calls for resources. But in a moment when nearly one-quarter of U.S. children speak a non-English language at home, it’s clear that English learners deserve more federal funding. Much more.

As I pointed out last spring, ESSA’s Title III, the core funding stream dedicated to English learners’ linguistic and academic development, was never sufficient to adequately support their success. It’s even failed at a more rudimentary level: since its inception in 2002, Title III funding hasn’t even kept pace with growth in the English learner population. The $664 million appropriated that year worked out to roughly $175 for each of the ~3.8 million English learners in U.S. schools in 2002. As of 2018 — the most recent year for which federal data has been published — there were more than 5 million English learners, so the $737 million appropriated that year worked out to just $147 per child. What’s more, this analysis doesn’t take inflation into account.

It’s not a complex situation: the United States is spending less per pupil on English learners now than we did in 2002, and that base amount was paltry to begin with. The solution should be commensurately simple: as many national English learner advocates have suggested, Title III should at least triple in size, to roughly $2.2 billion per year (still just $440 in federal dollars per student).

Atop this fundamentally critical funding increase, the report also calls for a series of targeted federal investments to shift how English learners are educated. Above all, these focus on rewiring the federal “English-only” approach to these students’ learning to instead support students’ English development and their emerging bilingualism. This tracks the emerging research consensus suggesting that well-implemented bilingual education programs are the best means of supporting English learners’ linguistic and academic development. In particular, two-way dual language immersion programs that integrate English learners and native English speakers in bilingual settings appear to be especially effective.

Here’s the good news: public demand for bilingual education has grown in recent years. Here’s the bad news: every local and state effort to expand access to bilingual programs has been limited by the monolingualism of the American teaching force. There simply aren’t enough bilingual teachers to go around. And, of course, scarcity almost inevitably produces inequity in public education — true to form, mounting evidence suggests that dual language programs are increasingly slipping away from linguistic integration towards primarily serving the needs of privileged, English-dominant families.

The project of expanding dual language programs in the United States is, at base, a subset of the broader goal of increasing teacher diversity. To that end, the report recommends two new federal grants programs: 1) a $200 million investment in creating and growing linguistically diverse teacher training pipelines, and 2) a smaller, $50 million funding pot for states willing to “pilot, redesign, and implement new bilingual teacher certification and licensure policies.”

As the country works to finally get the educational inputs right for English learners — more funding and better instructional programs — it’s also critical to update how we measure these students’ educational outcomes. At present, American schools only track the performance of linguistically diverse students up until the point when they reach their state’s definition of proficiency in English. After that, they are soon “reclassified” as former English learners and “exited” from that defined student group — meaning that their academic progress gets lumped in with the general student population. But this offers an incomplete picture, since former English learners’ performance in U.S. schools tends to improve with their English abilities.

To address this challenge, the report recommends including “former English learners” in federal requirements for school transparency and accountability systems. That is, local and state leaders should be required to keep track of how English learners perform academically after they become proficient in English. This would provide a more complete picture of their linguistic and academic development — and how well schools are supporting each.

To be sure, today’s report doesn’t fully represent the views of any one of the scores of people who read and responded to it. Everyone suggested fixes, and no one person’s changes were wholly adopted — I even cut a few of my own favorite ideas. But the document does include a battery of ideas supported by most of the English learner stakeholders who engaged with the text. The ideas are as specific and actionable as we could keep them, and — if adopted by policymakers in Congress and the U.S. Department of Education — would make a real difference for millions of linguistically diverse children across the country.

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

;)