Whitmire: Why Miguel Cardona Could Help End the School Culture Wars and Reverse College Enrollment Plunge for Low-Income Kids

A version of this op-ed appeared earlier in the New York Daily News

Oddly, Miguel Cardona, the relatively unknown Connecticut education commissioner tapped to be education secretary, is positioned to achieve something dramatic: reversing the scary plunge in low-income and minority students pursuing higher education.

Why Cardona? Because of who he isn’t.

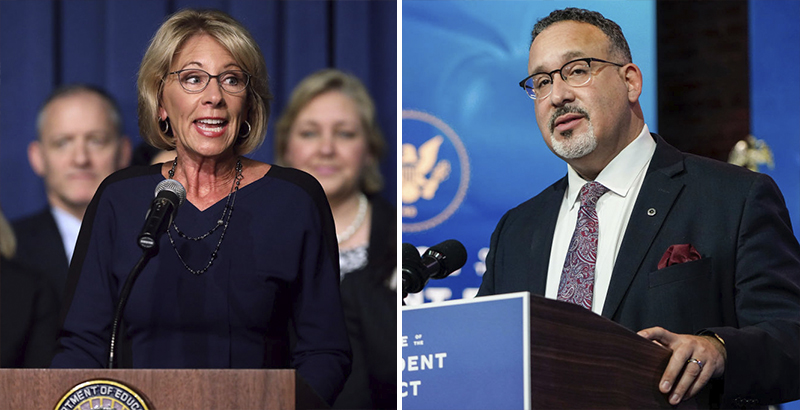

Cardona isn’t a Betsy DeVos of the Left. Thank goodness. The other two leading runners-up, an academic and a former union president, were both likely to wage pointless education wars on the Left, just as DeVos did on the Right.

Nor is Cardona a prominent school reformer likely to trigger the animosity of the powerful teachers unions, as Arne Duncan did under President Obama.

These are good things, because the best shot at turning around the free fall in college aspirations for first-generation college-goers is to engineer an end to the education wars, which focus mostly on the standoff between the two camps of public schools: traditional, unionized schools and mostly non-union charter schools.

Why the need to end the education wars? Because in recent years the top charter school networks pioneered something that has eluded most traditional school districts, greatly boosting the college graduation rates for those vulnerable students. Those networks are eager to share what they’ve learned with traditional districts, but they need partners willing to work together.

Now, more than ever, these two sectors need to collaborate, and there are plenty of small-scale attempts at collaboration that could quickly scale up and make a difference.

First, a quick look at the challenge ahead.

Earlier this month, the National Student Clearinghouse reported that college enrollment for low-income high school graduates declined by a shocking 29 percent, almost double the rate for students from higher-income high schools. And those numbers are worse than they seem: Many of those students from well-off neighborhoods are merely taking a gap year to avoid remotely taught classes. They will soon return to college, unlike their low-income counterparts working low-wage jobs to help out their families.

The story gets bleaker when you look at community colleges, the places where many low-income students end up. There, the drop was a dramatic 37 percent.

Is this a problem likely to get turned around quickly with a vaccine? Probably not. There are warning signs up and down the age continuum that signal enduring damage. In many urban districts, students are simply disappearing — either not joining remote classes or not enrolling in school. And there’s ample evidence that low-income students are not responding well to remote learning, in part because they lack the technical means.

Finally, there’s a truly worrisome drop in the number of applications for federal college tuition assistance, known as the FAFSA, or Free Application for Federal Student Aid.

What we’re looking at is potentially losing a generation of low-income college-goers. And given that current students act as important family role models for follow-up generations of first-time college-goers, the situation becomes critical.

So why would collaboration between charters and districts help? Because prior to the pandemic, low-income college-goers were experiencing growing success due to three factors. First, colleges were getting a lot more adept at keeping their students from dropping out. Second, major philanthropies stepped in to sponsor expert college guidance in high schools that couldn’t afford it.

The third reason may be the biggest player: The best charter networks, which serve large populations of low-income, minority students, figured out how to boost the college success rates for their alumni by two to four times the national average for similar students.

What’s the reason for their success? In short, using data to figure out what they were doing right and wrong to prepare their students for college and help them win degrees, and then adjusting accordingly. That data comes from only one source, the National Student Clearinghouse, a unique nonprofit originally created to track student loans for banks. In recent years, however, that data has been used for an entirely different purpose — tracking students through college, which gives high school counselors accurate data on issues such as which colleges students should attend to ensure they will actually walk away with degrees.

Sounds simple, but having this data, and using it expertly, are powerful tools. At the Uncommon Schools charter school network, for example, educators discovered that helping students push up their grade point averages even slightly dramatically improved their persistence in college. Why? Because the study-and-homework skills needed to improve a high school GPA turn out to be the very same skills needed to get through college courses.

Probably the biggest breakthrough by the charter networks was using Clearinghouse data for college guidance. Seemingly similar colleges can have dramatically different graduation rates for low-income students. And all the top charter networks formed teams of counselors to track their alumni through college, making sure their college progress didn’t get derailed by simple things such as renewing financial aid forms. Again, using Clearinghouse data was the key.

With some notable exceptions (Chattangoga and Chicago come to mind), traditional districts have been slower to take advantage of the data. There are understandable reasons: They’ve never seen college success as one of their missions (isn’t that up to students, parents and colleges?), they lack the data-crunching abilities to take full advantage of what the Clearinghouse offers and, in truth, they have so many other urgent demands on their plates.

But with collaborations with charter networks, the districts will find partners willing to share the nuts-and-bolts about how to make it work. Most compelling: districts will find corporations and philanthropies willing to step in both to fund the collaborations and provide data-handling muscle.

Anyone who thinks this can’t happen needs to visit San Antonio ISD, where visionary superintendent Pedro Martinez is making it happen with a collaboration with the KIPP charter network. That’s just one example of KIPP taking on this challenge.

If Cardona can forge more collaborations around college success, perhaps other types of existing collaborations can broaden. These already exist on a small scale, but charter/district animosities have blocked wider adoption.

Again looking at Uncommon Schools as an example. Since 2014 the network has collaborated with the New York City Department of Education on professional development for teachers. Its partnership with Newark Public Schools led to a boost in achievement for Newark district schools.

In Connecticut, Cardona never joined in the education culture wars over charters. When the pandemic struck, he included grass roots organizations and education reform groups in his plans. And his record has been all about boosting education opportunities for low-income, minority students.

Just looking around Connecticut, and the rest of the country, it’s clear that charters, which enroll just 6.5 percent of the nation’s K-12 students, are hardly an existential threat to districts. Thus, it’s time to set aside swords for ploughshares.

There’s a pandemic-generated education emergency at hand. Calling a truce to the education culture wars by encouraging charter-district collaborations would signal a strong start toward easing the crisis.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)