When It Comes to Predicting Which College Students Will Actually Go On to Attain a Bachelor’s Degree, High School GPA Is King

This is an excerpt from the new Richard Whitmire book The B.A. Breakthrough: How Ending Diploma Disparities Can Change the Face of America. See more excerpts, profiles, commentaries, videos and additional data behind the book at The74Million.org/Breakthrough.

In the charter school universe, Newark’s North Star Academy is fabled. It was one of the first high-performing charter schools, launched in 1997 with 72 students, succeeding with students growing up in a city that most Americans believe died long ago. And it is one of the most visited charter schools in the country. Charter startup entrepreneurs across the U.S. adopted parts of the morning Community Circle pioneered here, a mashup involving African drums, call and response, academic exercises, and awards — all fast-paced and loud, very loud. It sets the day for students and staff. It works.

North Star, part of Uncommon Schools, has been home to school leader Michael Mann for about 20 years. Over that time, he has invented and reinvented curriculum, discipline, school culture, pretty much everything that needed doing to succeed with students coming from challenging urban environments. And yet, after all those years, he was still watching a small percentage of high school students struggle and fail. Why?

As with any top charter network, success and failure are ultimately defined by college completion: How many of our students end up earning college degrees? College graduation is what parents are promised; it’s what makes these charters, with their longer hours and tougher discipline, palatable. One thing North Star discovered in its quest to understand why some students floundered trying to reach that goal was something that seems, on the surface, almost too simplistic to matter: North Star graduates with grade point averages above 3.0 are four times as likely to earn college degrees.

It was a pretty stark statistic: four times as likely. It couldn’t be ignored. As it turns out, all the student strategies involved in learning how to raise your GPA are the exact tactics students will need to persist in college. “Your GPA is the ultimate measure of grit in high school. That’s all about work ethic, about your ability to persevere,” said Paul Bambrick-Santoyo, who oversees Uncommon’s high school and professional development programs.

It’s not that test scores matter less. In fact, Uncommon found that raising SAT scores pushed up college success rates. “While we may fight it, the SAT is a very objective measure of college readiness. English and math are the foundations,” said Bambrick-Santoyo. In 2005, the average combined math and verbal score for North Star seniors was 932 out of a perfect 1600. Since 2012, the average scores have never dropped below 1,000, the result of programs designed to improve the SAT outcomes of North Star students.

“Those 70 points are more than marginal,” Bambrick-Santoyo said. “Our students have been dramatically more successful at handling college work when they’ve gotten above that bar.” Especially important, he said, was the SAT verbal score. “If you can’t read at [a] level to get a 500 [out of 800] on the SAT, you can’t handle college-level reading work, especially scientific articles.”

One of the major issues North Star teachers identified was that instead of thinking critically for themselves, many students would just listen and use the analyses of the one or two students who spoke up during class. As a result, all the students were able to write decent papers — but without ever truly understanding the meaning of what they were writing. They were getting free rides off those couple of students, a ride not available to them on tests or independent reading exercises.

That discovery led to an instructional change: After students finished a new reading, they wrote their own analyses first and discussed it in class later.

But test scores still don’t trump GPA. That’s the conclusion of a recent study by Matthew M. Chingos, director of the Urban Institute’s Education Policy Program. The study, part of a “What Matters Most for College Completion” project, also settled on grades as the most important predictor.

“This makes sense given that earning good grades requires consistent behaviors over time — showing up to class and participating, turning in assignments, taking quizzes, etc. — whereas students could in theory do well on a test even if they do not have the motivation and perseverance needed to achieve good grades.”

—Matthew Chingos, “What Matters Most for College Completion”

The path that North Star took to boost student GPAs is only one of many strategies adopted by top charters to drive college success rates. Not to mention exposing students and parents to college counseling. There are too many to detail all in depth, so I will focus on just this one, raising the GPA, because it reveals much about the hard work, surprises, adjustments, and readjustments that go into the process of increasing college success. Truly, this is rocket science.

“Both SAT or ACT scores and high school GPA are associated with the likelihood that students at four-year colleges earn a bachelor’s degree. But when considered together, the predictive power of high school GPA is much stronger,” writes Chingos:

This makes sense given that earning good grades requires consistent behaviors over time — showing up to class and participating, turning in assignments, taking quizzes, etc. — whereas students could in theory do well on a test even if they do not have the motivation and perseverance needed to achieve good grades. It seems likely that the kinds of habits high school grades capture are more relevant for success in college than a score from a single test.

Solving a mystery: The link between absences and failure

Why, after all these years, was Mike Mann, North Star’s head of school, still seeing students with poor grade point averages? He knew two of the reasons: poor work ethic and learning disabilities. When he first began working on the issue, he didn’t suspect there was a third, undiscovered reason. Poor work ethic is an obvious one any educator knows about. Its most recognizable symptom: not completing homework.

“Some parents struggle in getting their children to do their homework, and the students are unmotivated. So that’s one reason,” said Mann. “The second, learning disabilities, is another obvious one. These are the students who are highly motivated, turn in all their homework, and still fail on tests. We know that one well. We have things in place, both in general education and special education, to address that.”

But Mann suspected there was a third reason. “For a long time, I couldn’t find it. It was like dark matter; it took me a long time.” Eventually, the dark matter revealed itself to be absences. When students who were already doing poorly were absent, they lacked the motivation to check in with their teachers to see what work they missed. They just let it slide, which means that day’s assignment registered as a blank in the teacher’s grade point records. On the surface, the student’s grades might seem OK, but at the end of the marking period, when the teacher pushed the button on the laptop to calculate the grade, all those blanks became zeros. The result was an awful or failing grade that was too late to do anything about.

“We hadn’t seen this before,” said Mann. “As a result, we weren’t taking care of it.” So Mann set out to correct the problem. In the student dashboard, where students can view all their coursework and current grades, there’s now a second column, right after the homework completion column, that cites unfinished work. Now, there’s no hiding from it. Plus, the school designed a new grading system for teachers, so that they enter zeros right away, rather than leaving blanks. Again, no hiding from it.

Students confront their shortcomings and boost their GPAs

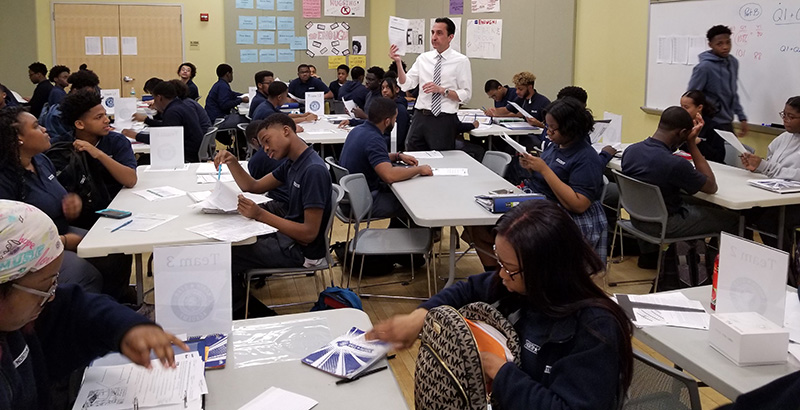

The Target 3.0 program at North Star is Mann’s baby. He designed it; he teaches it; he invented the remedy and then he reinvented the remedy when it was clear he was on the wrong track. On the day I visited, the class of 72 students (out of 614 in the school) included every student in the 10th, 11th, and 12th grades with a GPA less than 2.5. Think about that for a moment: The lowest-performing students, all (unhappily) gathered in a very large room with a single teacher. In most schools that’s a recipe for a disaster — unruly students and a teacher who bails out at the end of the year, if not before. That’s why Mann took it on himself.

Mann cites three reasons for being personally involved in turning around the GPAs of his lowest-performing students. First, he’s the creator, so he’s constantly tinkering with it. Target 3.0 required inventing a new student data dashboard. Uncommon didn’t have one, but Noble Network of Charter Schools in Chicago did, so Mann knew he would have to borrow and adapt — something a school leader has the clout to do. Second, the students wouldn’t take it seriously unless the school leader did it. Third, he learned a lot — such as discovering the mysterious reason why some student GPAs took a sudden plunge when teachers pressed the calculate-GPA button.

The students file in and sit at assigned tables, or “teams,” where they must talk about their lagging grade point averages. It’s called an “accountability conversation,” and each student describes a “smart goal” for turning things around in their worst class. The following week, they will have to explain how they met, or didn’t meet, that goal. To make sure the questioning is unsparing, Mann provides a script for the students to read as they address fellow students: “The script language is pretty blunt. We think that makes it sound more real. And at the beginning of the semester, we make them practice the script. They go through the whole script: ‘OK, you said you would go in to see Miss Dash to get the quiz done. Is it done? No? So you were either lying to us or something else happened.’” Why? If parental pressure doesn’t work, and teacher pressure doesn’t work, maybe peer pressure will have an impact.

There’s no escaping having your personal “stuff” aired in a Target 3.0 class. Peer pressure is pretty much the whole point, starting with the name of every student [if he or she grants permission] projected on a giant screen, accompanied by their GPA. That’s on top of lots of color-coded papers students receive (not to be shared with others) that lay out every detail about their academic life at North Star. Many use their own cell phones to track their successes and failures using PowerSchool, a how-you’re-doing-in-school online platform that can be shared with parents. Like I said, there’s no hiding here. After all the data accountability demands get met, some students are dispatched to visit teachers to settle how those assignment “blanks” get filled in, thus avoiding the zero debacle.

It all seems to work, especially with the older, more mature students. Within a semester, all the seniors boost their GPAs above a 2.5. For juniors, that rate is 74 percent. Only half the sophomores make the leap. That will change, Mann assures me, as students advance through the grades.

Senior Malaya Pleasant is blunt about her past failings. “For my first two or three years of high school, I just never cared. I know that’s bad, but for years I didn’t. In the beginning years of high school, I didn’t realize that, oh, I have to go to college after this, that I have to prepare my GPA in order to do something after high school. So I struggled a lot. I took Advanced Placement classes that I wasn’t ready to handle.”

“By the end of the year, I’m trying to get at least a 2.8 or 2.9. My target is 3.0, but I know that’s kind of unrealistic.”

For the past two years, she has been in Mann’s Target 3.0 classes. Her turning point came this year when Mann chose her as a group leader, one of the students in charge of each small group that sits together in the large classroom. Helping other struggling students prompted her to improve. “So I got my agenda [a record of all school assignments, test days, etc.] and started writing down my homework every day. Organization is key. Like, if you’re not organized, I don’t know how you survive.”

She found herself in charge of helping three students: a transfer from another school, a student with behavior problems who was chronically absent, and a student who seemed to have no purpose in school. “That last one was similar to me, so I connected with him the most.”

She made progress with that student, and she is meeting with the student with behavior problems. “I’m asking why he’s acting out and why he is not utilizing the resources the North Star gave him to succeed.”

But the biggest turnaround may be herself. Being asked to be a leader was something special, something that had never happened to her. At the beginning of her senior year, her GPA was a 2.4. By the time I visited, in April of 2018, it was up to a 2.7. “By the end of the year, I’m trying to get at least a 2.8 or 2.9. My target is 3.0, but I know that’s kind of unrealistic.”

Already, college is firmly in her future. She has acceptances from Stockton University in Galloway, New Jersey, and Morgan State University in Baltimore, Maryland. Her goal: to become a forensic psychologist.

Sophomore Alex Lopez has been at North Star for five years. “My first two years were not the best. I have always struggled with science and math because I was never good with numbers.” Little things, such as making sure he wrote down everything in his personal agenda, helped him complete homework. And making sure he did his homework at school, in a study hall period, rather than at home, helped as well. At home, other distractions, such as the TV or the phone, were too strong a pull. Often he would forget about homework assignments until late at night. “Then I would stay up until 2 a.m. trying to do homework and come to school tired with only four hours of sleep.” Since that shift, he’s been getting to bed around 10 p.m.

Currently, Lopez’s GPA is a 2.33. Even though college is two years away, he’s aware that his current grade point average falls short of dream acceptances, such as Boston College, which he thinks would require a 3.6 or higher. “I don’t want to stress over that because I know if I start stressing then I’m going to overwork myself, and when I do that, everything just becomes a mess.”

Teaching K-12 kids college survival skills

The college success strategies at most of the big charter networks resemble one another, which is not surprising considering the cross-fertilization among them. At KIPP, a leader in pushing hard for better college completion, three strategies emerged. First, the network departed from its middle-school-only playbook and expanded in both directions, elementary and high school. The reason is simple: A student who stayed with KIPP through high school had a far better chance of earning a degree than a student who only went to a KIPP middle school. KIPP also built an elaborate KIPP Through College program that uses college selection science to pick just the right school for its graduates and then tracks them through college, using specially adapted software from Salesforce, which writes software for businesses.

And KIPP also embraced the findings of researchers such as Angela Duckworth, who pioneered a self-reliance strategy popularly known as grit. Her research lined up with what KIPP co-founder Dave Levin had noticed early on, that the students most likely to earn degrees weren’t necessarily those with the best academic records. Rather, they were the students with resilience, an ability to bounce back after a bad grade, the students outgoing and confident enough to seek out help from professors.

These were the students most likely to make the transition from the hyper-controlled high school experiences at KIPP to the anything-goes realities of a college campus. KIPP’s “character counts” program led to the posting outside all classrooms of the seven “strengths” that need developing beyond competency in math and reading. They are: zest, grit, optimism, self-control, gratitude, social intelligence, and curiosity.

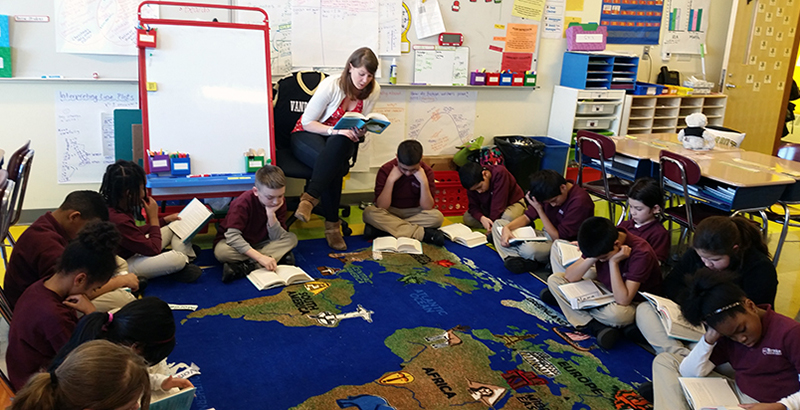

At other charter networks, the changes made to boost college success might look a little different, but they share one commonality: making students more independent learners and thus more likely to survive on a college campus. At Boston’s Brooke Charter Schools, for example, which just launched its first high school and has yet to send any graduates to college, the mindset begins in the earliest grades.

During one visit there, I watched fourth-grade teacher Heidi Deck practice “flipped instruction,” in which students, when presented with a new problem, are first asked to solve it on their own, armed only with the tools of lessons learned from previous problems. “We really push kids to be engaged with the struggle,” said Deck. Next, she invites them to collaborate with one another to solve the problem, followed by more individual attempts to do the same. Always, Deck expects the students to figure out the puzzle.

This is exactly the opposite of the most common approach to instruction, in which teachers demonstrate and then have students practice what they just watched. That’s dubbed the “I do — we do — you do” approach. With flipped instruction — and the many other teacher innovations here — “kids have to do the logical work of figuring something out rather than repeating what the teacher does,” said Brooke’s chief academic officer, Kimberly Steadman. The goal: Starting with its Class of 2020, the first graduating class Brooke sends off to college, all its students will be independent learners, able to roll with the surprises that confront all college students, especially first-generation college-goers.

Preparing students to be self-directed learners, regardless of whether they pursue college or a career, is at the heart of the radically different Summit Learning program, which grew out of the Summit charter schools in Silicon Valley. As happened at many charter networks, Summit discovered its college success rate was lower than expected, in part because its students were too micromanaged in high school. In short, a failure to create self-directed learners.

To create academic independence that will help their alumni make their way through college to win a degree, Summit shifted to self-directed learning, coordinated by sophisticated software developed with the help of Facebook engineers. There’s some traditional teaching, but often the teachers act more as facilitators, tutors, or advisers. Rather than expand its charters, Summit chose to grow by offering its learning program to both charter and traditional district schools. As of the summer of 2018, the Summit program was being used at 330 schools in 40 states and the District of Columbia.

At Rhode Island’s Blackstone Valley Prep, I watched 15-year-old Ray Varone use the program on his Chromebook. He could view all his courses, including projects done, projects completed, and tests yet to be taken. A vertical “pacer line” shows him exactly where he stands in each course. For resources, he can draw from hundreds of “playlists,” which are learning tools such as online instructional videos from Khan Academy to help with math problems.

“We’re getting used to doing this on our own,” Varone told me. “In college, you’re not going to have teachers there asking you questions all the time, so you have to learn by yourself.”

That’s what self-directed learning is all about, and it’s what the charter networks hope will push up their college success rates with first-generation students. To date, the data suggest it’s helping.

This is an excerpt from the new Richard Whitmire book The B.A. Breakthrough: How Ending Diploma Disparities Can Change the Face of America. See more excerpts, profiles, commentaries, videos and additional data behind the book at The74Million.org/Breakthrough.

Disclosure: The Walton Family Foundation funded a writing fellowship that helped produce The B.A. Breakthrough and provides financial support to The 74. The 74’s CEO, Stephen Cockrell, served as director of external impact for the KIPP Foundation from 2015 to 2019. He played no part in the reporting or editing of this story.

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

;)