When $7B in Remediation Falls Short: The Broken Promises Colleges Make to Students Who Need More Help

Ninety degrees on a May afternoon, and New York’s streets wilted under unexpected heat. Pedestrians kept close to the shadow of buildings. Car chrome sparkled in the traffic.

It was different downtown, at the Tribeca campus of the Borough of Manhattan Community College, where the giddy spirit of students at a celebration of the school’s clubs felt more like a day at the beach. “Who was supposed to bring the water guns?” a flushed club leader, sweater draped over her head nomad-like, asked several people earnestly.

With 27,000 students, BMCC is the largest of the seven community colleges in the City University of New York system (which also has 17 four-year and graduate schools). Its size helps keep it near the top of the list nationally in the number of degrees it awards. A few blocks from the Freedom Tower, it is also the only campus that had a building destroyed in the 9/11 attacks.

What isn’t clear from the festivities in front of the school, whose enormous main building stretches four city blocks along the Hudson River, is that not only will most students fall short of a degree — about 40 percent nationally who started community college in 2010 earned a credential in six years — but also that 80 percent of the school’s incoming students each year are assigned to remedial classes, according to administrators.

From that moment, if averages hold, their chances of earning a degree — of even passing a college course — sink. And the more remedial classes they need, the dimmer their academic future.

Some will beat the odds. A cheerful young woman named Alexis, about to complete her studies at BMCC, sits with friends at the student activities table. She explains that unlike most there, she’s not from New York. Her friends nod as if New Jersey must have been hard to overcome.

“Freshman year I took two [remedial classes] in math,” she said. “I missed the score by one point! I was so mad. But I forced myself to get it done.”

Alexis, along with one of her friends and most of her schoolmates, ended up in remediation because they didn’t score high enough to meet cutoff points on either the SAT (480)/ACT (20) or New York State Regents exams (75) to be eligible for college-level classes in math, reading, or writing — and sometimes all three.

As the BMCC students partied in the sun, others accepted for the fall were inside taking placement tests that would determine the course of their career at BMCC and possibly directly affect the rest of their lives. The tests are a lifeline of sorts: If a student passes, they avoid remedial education despite low scores on the other exams.

If they fail, they’ll be assigned to classes that, in essence, give them a second chance to learn what high school should have taught. The hope is that they gain the foundational skills and knowledge the tests say they lack to have a fighting chance of succeeding at more difficult work.

In a sense, community college remediation — called “developmental education” by those who design and study it — is highly idealistic in its attempt to make a space on the launchpad of American higher education for virtually any high school graduate, however badly prepared, impoverished, and constrained by language, disability, or other life circumstances.

These students skew poor and minority: 78 percent of all black community college students take a remedial course, as do 75 percent of Hispanic students and 76 percent of poor students.

The problem is that remediation doesn’t work, or not very well, except with the most unprepared students who complete their entire sequence of remedial courses. The problem has been clear since researchers began to assemble large sets of outcome data about 15 years ago. Solutions are less evident: If students are already behind in early elementary grades, how can a college be expected to elevate them over a year or two in their late teens?

Completing college became a higher priority generally over the past 15 years in response to economic and technological change. In higher education, data became more plentiful as well, and efforts to reform developmental education began to percolate across the country. Advances in Colorado, Tennessee, Florida, and California and in district-college partnerships have made analysts optimistic.

“Given where the [remediation] rates are, maybe it wouldn’t be crazy to see those rates cut in half in 10 years,” said Scott Sargrad, the managing director for K-12 policy at the Center for American Progress, a liberal think tank.

Optimism still sits alongside the history of remediation failure, however; a CAP report last year called developmental education “a systemic black hole from which students are unlikely to emerge.”

A $7 billion–a-year intervention

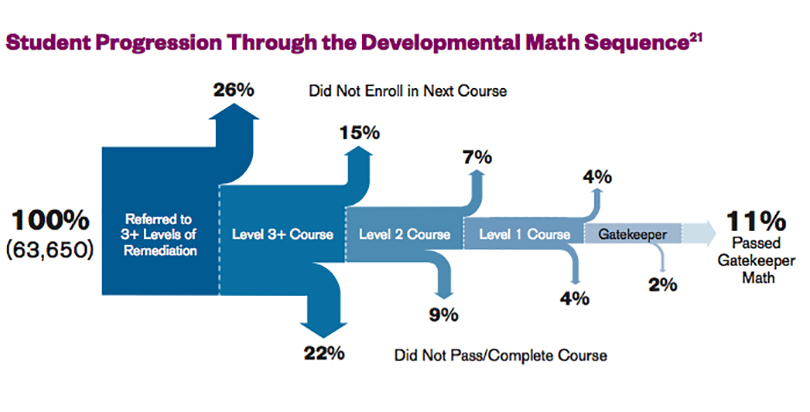

Community colleges have worse performance results because they a–e open to almost all comers. But their remedial numbers stand out. Only 1 in 5 students placed in remedial math classes (some are required to take two or more) ever went on to pass a “gatekeeper” class in math — the required, entry-level college course. Only 37 percent do in reading.

The data reflect the unusual demands of remedial courses. Students may be forced to take several semester-long courses of questionable usefulness and quality for no credit, each costing as much as a credit-bearing course (about $1,200 at CUNY community colleges). That’s not a high figure to some, but half of CUNY students come from families earning less than $20,000. Many have family and work responsibilities; the average age of a CUNY community college student is 24. Research has found that the longer students are asked to remain in school — not just when paying for courses that don’t carry credit — the less likely they’ll finish.

Many never show up for remedial classes or stop during the semester, sometimes ending their college career before it begins. A 2011 National Governors Association–backed review of 33 states found that less than 10 percent of students assigned to remediation earned the two-year associate’s degree in three years.

In a 2009 study, only 11 percent of students assigned three remedial math courses passed an entry-level college algebra class. More than a quarter never enrolled in the first remedial class. (Source: “What We Know About Developmental Education Outcomes,” Community College Research Center, Teachers College)

In 2010, a team led by education economist Tom Bailey at Columbia University’s Teachers College found that more than 70 percent of students who skipped their remedial placements to enroll directly in a college course passed it, while only 27 percent of those who enrolled in their remedial coursework, as assigned, went on to pass the college course. The large difference was due in part to the number of remedial enrollees who simply dropped out. By contrast, those who completed remedial coursework performed better in the gatekeeper class than those who skipped remediation.

“It appears that the students in this sample who ignored the advice of their counselors and proceeded directly to college-level courses made wise decisions,” the authors wrote.

It’s literally not a small problem. Half of the country’s undergraduates enroll in remedial courses, and those who do take an average of 2.6 classes, according to an influential 2011 study conducted by Judith Scott-Clayton and Peter Crosta of Teachers College and Clive Belfield of Queens College. Given 3 million students entering college yearly, and assuming the costs of remedial courses to be the same as classes with credit, the researchers calculated that students spend $7 billion each year on remediation.

That makes developmental education “perhaps the most widespread and costly single intervention aimed at improving college completion rates” after financial aid. Yet Scott-Clayton and her colleagues found that the tests most commonly used to identify students needing remedial work “severely misassigned” the test-takers: About one-third were assigned to remediation but didn’t need it, while a smaller number needed it but weren’t assigned.

The study found that if colleges used high school performance in addition to screening tests, “they could remediate substantially fewer students without lowering success rates in college-level courses.”

While research continues to document the hazards of traditional remedial systems, academics and practitioners believe the data offer a through-line to better practice.

“I think if you asked, in the late ’90s, a community college president what their graduation rate was, they probably couldn’t have told you because we didn’t have good longitudinal data,” Bailey, of Columbia’s Teachers College, said in an interview.

Today, he said, “there’s a widespread sense that there’s a movement taking place.”

Photo: Courtesy City University of New York

Speed is of the essence

CUNY has become an innovator in readying students for college through an array of prep and accelerated programs and what’s known as corequisite courses, allowing students at remedial levels to take college courses while receiving extra support. The university, which enrolls 270,000 full-time students, hasn’t used remediation in its four-year colleges since 1999, but it remains in place in the two-year colleges.

ACCUPLACER, a short standardized test produced by The College Board, is used to assess reading and math for students who scored below SAT/ACT and Regents cutoff points. ACCUPLACER continues to be used nationally for remedial screening despite the high error rate identified in the Scott-Clayton research (the company recommends that it not be used without other measures). “Based on the Scott-Clayton study,” CUNY said, “we are also developing a means of taking high school grades into account.”

About 75 percent of students entering CUNY need math work. Some colleges have remedial sequences of three courses or more, but CUNY typically requires no more than two, according to the administrator.

Nationally, 68 percent of community college students are referred to remedial classes along with 40 percent of four-year students. Students identified for remediation in four-year colleges tend to come from more affluent backgrounds, probably in part because there are fewer poor students in those institutions. Recent reports from CAP and Education Reform Now emphasize the failure of the K-12 system in identifying the relatively large numbers of middle- and upper-middle-class students in four-year colleges who need remedial instruction.

“People are underestimating the breadth and depth of high school underperformance. They think it’s not their kids,” Michael Dannenberg, a co-author of the ERN study, told The Washington Post.

Community college is a good investment: A graduate earns $5,400 more annually than a dropout. The rule of thumb among advocates and practitioners has become getting students — and especially those in remedial work — to graduation without delay.

“Recent research has shown that students who are assigned to remediation do best when they complete their remedial instruction quickly,” said David Crook, CUNY’s associate university provost for academic affairs.

Complete College America, an advocacy group, is more blunt in its 2011 report Time Is the Enemy: “The longer [graduation] takes, the more life gets in the way of success.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)