What Research Says About Mass. Charter Cap Debate: From Graduation Rates to School Funding

A pitched debate continues to escalate in Massachusetts on whether the state should allow for the expansion of charter schools. After a potential legislative compromise fell apart last spring, an initiative, pushed by charter advocates, will appear on the November ballot.

Charter schools in some areas in the state cannot significantly expand because of a cap limiting how much money districts can spend on charters. If the measure, known as Question 2, is approved by voters less than three weeks from now, an additional 12 charter doors would be allowed to open across the state each year.

Let’s break down the two arguments:

1. Are Boston charter schools really that good?

Charter advocates point to research showing that Boston’s charter school students significantly outperform those who applied to attend a charter in the city but weren’t admitted. Skeptics claim these gains are based on standardized tests and result from, as Massachusetts Teachers Association President Barbara Madeloni put it, “hyper-controlled test prep factories.”

A flyer from the “No on 2” campaign says, “The tightly controlled atmosphere in charter schools may in part explain why charter school students struggle in college … [S]tudents who graduated from the BPS had a greater chance of success in college, with 50 percent of BPS high school graduates — but only 42 percent of Boston charter high school graduates — obtaining a college degree within six years.”

This assertion has also been made by Madeloni, and several others, all citing a 2015 study from the Boston Foundation.

There are several significant problems with this claim, however. “These comparisons are extremely misleading and are contradicted by the very study that they cite,” said Sue Dynarski, a University of Michigan economist who has researched the effectiveness of Massachusetts’s charters. A spokesperson for the No on 2 campaign did not respond to a request for comment.

First, the 2015 paper is now outdated. A more recent (January 2016) report from the Boston Foundation found college completion rates were basically even between charter and district schools (51 percent and 50 percent, respectively). The campaign flyer is dated May 2016; it is unclear why it relies on old data.

Second, the statistic does not reflect the totality of students in each sector but solely the students who graduate high school and then enroll in college — a relatively small fraction of kids.

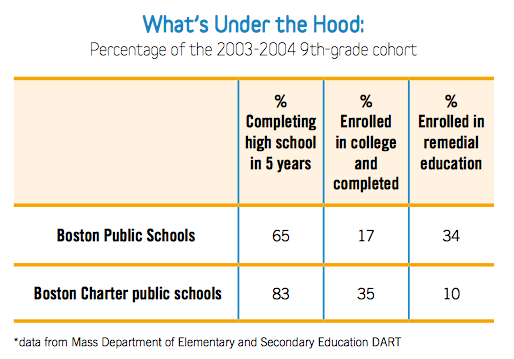

In fact, if you look at all students, those attending charter schools do much better. According to the 2015 Boston Foundation report, 25 percent of charter school students graduated college within six years, compared with 17 percent of all Boston Public Schools students. In the 2016 report, the advantage among charter students had increased to 35 percent versus 17 percent. These figures were confirmed by the Boston Foundation.

Source: The Boston Foundation

Third, and most important, these raw numbers cannot be used, one way or the other, to judge the performance of district and charter schools. Why? Because the students who choose to attend charters may be different from those who go to traditional public schools. That is precisely why researchers prefer instead to compare those students who applied to a charter and got in versus those who applied to a charter but failed to secure a seat.

By this measure, attending a Boston charter school leads to large gains on state tests, advanced placement exams and the SAT. Charter school students also are more likely to attend a four-year college rather than a two-year program, which in other research has been linked to a greater likelihood of degree completion. (There is no direct evidence yet on how Boston charter schools affect college completion.)

The one place charters are at a disadvantage is in four-year high school graduation rates, though that gap disappears when looking at five-year graduation rates.

Test score gains for students at the city’s charter schools persist across differing research methods, for special education students and English-language learners and even for students who don’t apply through a lottery. There is also evidence that those gains are not likely the result of teaching to the test.

In short, Boston charter schools significantly outperform the city’s traditional public sector by most measures. The oft-cited data on charter school students struggling to graduate college are outdated, incomplete and inappropriately used.

2. Do charter schools mean more or less money spent on public education?

Another flashpoint of the Question 2 debate has been how the expansion of charter schools affects district schools’ finances. Opponents of the ballot measure say that as more students have enrolled in charters, nearby district schools have lost $450 million in funding. Charter advocates respond that money appropriately follows the student and that Massachusetts sets aside special funds to ensure that district schools get extra money for several years after a student transitions to a charter.

The pro-charter campaign has gone so far as to say, “Question 2 will increase public education funding,” because of this transitional aid. The two sides have released competing ads on the issue:

So who’s right?

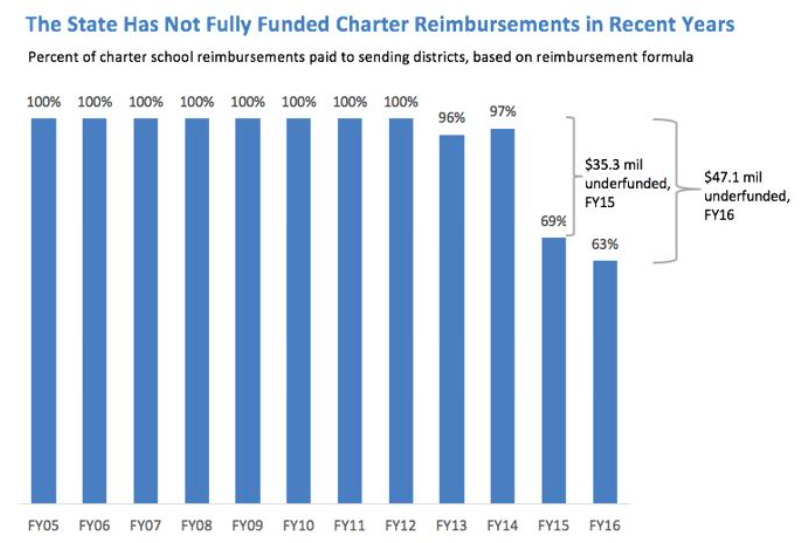

First, nothing in the ballot initiative would create a new revenue source for schools. When charter supporters say “more money” for public schools, what they’re referring to is the state’s relatively generous reimbursement aid that goes to schools that lose students to charters. However, this aid has not been fully funded by the state in recent years, and the money that is spent there has to come from somewhere.

While it’s true that reimbursements are supposed go to schools that lose students to charters, the total amount of money spent on public schools statewide may be unchanged even if charters grow. Although it’s possible that policymakers will allocate more money to account for an expansion, it’s also possible that they will simply further underfund the standing pot of aid. Nothing in the ballot question addresses reimbursement aid or would guarantee that additional state funds get sent to schools.

Second, it’s clear that expanding charter schools can create fiscal stress on districts as students leave for charter schools. Randall Reback, a professor at Barnard who has researched the issue, says the problem is that it’s difficult for school districts to quickly reduce costs at the same rate as they lose students. For instance, spending on school facilities remains essentially unchanged, regardless of how many students attend the school.

As a report from the Massachusetts Budget and Policy Center put it, “Districts often can’t recoup the full per pupil cost of a departing student. Students going to charter schools are usually sprinkled across classrooms and schools, so even if the total number of exiting students is equal to the size of a full classroom or school, it is often impractical to close them immediately.”

A spokesperson for the Yes on 2 Campaign said in a statement, “Our campaign is built on claims made by bipartisan, independent institutions that have concluded that public charter schools have not only delivered an amazing education to the kids who need it the most, but also led to more spending on public school students. Meanwhile, the special interests opposing Question 2 have built their campaign on the lie that charters have taken $400 million from district schools — which independent institutions have called ‘absurd’ arguments used to ‘scapegoat’ charter schools.”

Many charter supporters point to a paper from the Boston Municipal Research Bureau that states that “charter expansion has not been a revenue issue for Boston Public Schools,” noting that the proportion of education dollars going to the district is closely in line with its share of students.

However, the paper goes on to explain that the growth of charters has led, in part, to “excess capacity” — meaning too many schools and too few students. In other words, in order to reduce costs, schools will likely have to close, an option already being explored by the district. As the report puts it, “More charter seats would further reduce BPS enrollment and demand that the BPS eliminates excess capacity through the consolidation of classrooms and the closing of schools.”

Reback says the state’s reimbursement aid may cushion the blow, but he adds that ultimately districts that lose students to charters will have to cut costs, which likely means laying off staff or shuttering schools. In districts losing many students, such as Boston, the fact that per-pupil spending remains unchanged, or even increases, does not preclude the necessity of these tough decisions in the long run.

Are school closures a good thing? Some argue that diverting money from district schools to potentially more effective charter schools makes eminent sense, while others say that closures have negative impacts on students and communities.

The research is mixed on how school closings affect student outcomes. In general, studies on the impact of charter schools on the performance of nearby district schools show either small positive effects or no effect whatsoever.

Of course, shaping this dispute is the issue of framing and definitions. Charter opponents say that the diversion — or “draining,” “siphoning,” etc. — of money from district schools has deleterious effects. Charter advocates counter that since charters are considered “public schools” by state statute, sending money to charters cannot, by definition, reduce money spent on public education.

Regardless, it is misleading to suggest that the ballot initiative will necessarily lead to additional money for public schools or that it will have no effect on the finances of districts where charters expand. While reimbursement aid may (or may not) increase in the short term, districts will eventually have to deal with questions of layoffs and closures. For better or worse, the impact on district schools — the diversion of money and their potential closure — is built into the theory of action of charter school expansion.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)