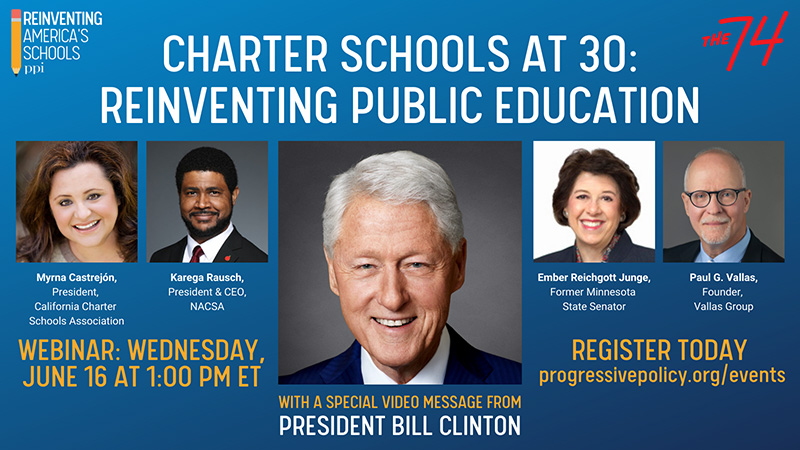

WATCH — Reflecting on 30 Years of Charter Schools: Former President Clinton Joins Panel of Education Experts to Assess the Movement and the Moment

Get essential education news and commentary delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up here for The 74’s daily newsletter.

“Keep America in the future business.”

Those were the words of former President Bill Clinton as he offered a hearty endorsement on Wednesday to the charter school movement 30 years after a bipartisan coalition in Minnesota passed the first law authorizing charters in the state.

But the bright future that Clinton and other charter supporters saw three decades ago faces a much different political environment in 2021. Bipartisan support crumbled in the hyperpolarized politics of the last several years, and teachers’ unions are firmly aligned against them.

The erosion of bipartisan support “was certainly not something that happened overnight,” said Myrna Castrejón, President of the California Charter Schools Association. “In recent years, there’s been a nonstop campaign of misinformation that is intensive and intentional by labor unions that have divided the educational community and elected officials by creating this false choice of us-versus-them.”

Castrejón was among the speakers in a panel discussion marking the 30th anniversary of charter schools, sponsored by the Progressive Policy Institute and The 74. Clinton, who signed the federal Charter School Program in 1994, offered opening remarks.

“We need to increase the cooperation and partnership between charters and public schools so we can keep delivering better outcomes and give all our students the opportunities to thrive, no matter who they are, what they look like, where they live or where they go to school,” Clinton said.

According to Castrejón, much of the political struggle over charters arises from competition — and charters’ success. In recent years her state of California has faced declining public school enrollment and “real serious budget pressures” at a time when charter schools have grown. “We serve 700,000 students, more than 1,300 schools,” she said. “It’s not a surprise at all that the competition and opposition have become formidable.”

Given the intense opposition among teachers’ unions today, it’s something of a paradox that one of the pioneers in the charter movement was Albert Shanker, who first proposed the concept when he was president of the American Federation of Teachers. Ember Reichgott Junge, a former Minnesota State Senator who introduced the state’s 1991 law, called Shanker a “visionary.”

“His idea of chartering was about providing teachers with the opportunity to take leadership, to be the professionals who they were, to try new ideas, to be leaders in the classroom,” Junge said. She also gave a shout-out to the Citizens League, which wrote Minnesota’s law. It was “a community group of urban leaders, civic leaders, labor, business, all coming together to say ‘we want to improve education’,” she said. “Chartering came from outside the political system.”

One of the big issues facing charter in the present day is the balance between accountability and giving charter schools the freedom to innovate, said Karega Rausch, President & CEO of the National Association of Charter School Authorizers.

“Finding the right balance of oversight while maximizing the time educators can spend on teaching and learning, that is absolutely a space in the charter movement that we’ve not quite gotten right at scale yet,” Rausch said. “And that’s why we see uneven performance of charters around the country.”

“We have some places where charters are so overly regulated they can’t do anything innovative or interesting and some places where they’re just operating without much oversight happening.” But he said he sees positive signs in governmental bodies and philanthropic groups of “investments in developing smart oversight.”

“It’s not necessarily about more oversight or less oversight; it’s about the right oversight that can allow for creativity and innovation to occur while still maintaining the public trust,” Rausch said.

Paul Vallas, who led the broad transformation of New Orleans schools into a charter-focused system after Hurricane Katrina, pointed to a straightforward formula for ensuring the success of charters “on a micro level.”

“Individual charters are successful when you carefully select the models, when you incubate the leadership, when you hold those schools accountable and when you make the determination of renewal based on their performance,” Vallas said. “But on a macro level, if one school is successful but at the expense of other schools, then are you really a success?”

Vallas also warned about the consequence of creating overcapacity with new charter schools and pointed to the success of so-called renaissance schools, like those in Camden, N.J. and Indianapolis.

“This is a situation where they’ve gone into the neighborhoods, they’ve worked with the neighborhoods, they’ve taken failing schools, they’ve transformed those schools into charter schools with no displacement of children,” he said. “You don’t create overcapacity, you’re creating quality choices and you’re basically getting the community to embrace the model.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)