Want to Make Gifted Education More Equitable? First, Be Aware of the Political Winds That Drove (and Derailed) Innovative Policies in These States

A bill that could have helped close the access gap to gifted education programs stalled out in the Washington state legislature Tuesday night, potentially ending for this legislative term a measure that advocates call “the absolute right thing to do.”

The bill would have required universal screening for gifted students and supported professional development to help educators identify and serve them. This is important at a time when low-income and minority students are shut out of gifted programming due to biases in screening or lack of access to testing: Children in poverty and minority groups are 250 percent less likely to be identified for gifted and talented programs than their white, more affluent peers.

But legislation like this faces the challenge of funding that comes with testing all students and requiring professional development to train teachers. And sometimes, advocates say, these bills can take on too much at one time.

“There are multiple steps to creating effective gifted education programs, and I don’t think you need to take all the steps at once,” said Brandon Wright, editorial director at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute. For comparison, Wright pointed to Illinois, which passed a universal screening bill for gifted students in 2016.

Unlike Washington’s bill, the Illinois legislation didn’t include any support for teacher professional development. The team behind that bill — Empower Illinois — described its process as “sequencing policy,” meaning that the passage of the 2016 bill mandating equitable screening for all student groups was just the first step. Last year, the team worked to get funding for gifted students by supporting the passage of Illinois’s tax-credit scholarship, which parents of gifted children could use for their education. The third stage, which the team is currently working on, supports fully funding public education. Rallying for fully funded gifted education will come in later years.

Myles Mendoza, executive director of Empower Illinois, said the majority of people support making gifted programs more equitable, but there’s still some opposition: Some think this could create an “affirmative action”–type system, some educators think there aren’t any gifted students in their schools, and others argue against having any gifted programs at all.

“These are the issues that should align with the ed reform movement if they believe in equity,” Mendoza said. “You can argue if you should even have [gifted programs], but if you have them, don’t just have them for upper-class white kids. You need to have them everywhere.”

In Washington state, some supporters of the bill said the issue came down to time. Though the House Education Committee unanimously voted for it, the legislation was introduced late in the already short 60-day session. Additionally, though the measure was revised to make professional development for teachers and administrators optional rather than mandatory, it didn’t have a note explaining fiscal impact, making pickup by the Appropriations Committee difficult.

But because the bill could affect the budget, its passage is not completely without hope and could be addressed before the session concludes March 8, said Republican Rep. Brandon Vick, who co-sponsored the bill.

“This is an issue that’s gaining in popularity,” Vick said. “A lot of folks are being left out of the [identification] process because there’s not a consistent message on how to identify kids and test kids.”

Nationally, two-thirds of schools have programs for gifted students, a number that stays consistent regardless of student poverty level, according to a recent report from the Thomas B. Fordham Institute. However, in low-poverty schools, 12 percent of students participate in gifted programs, compared with 6 percent of those in high-poverty schools.

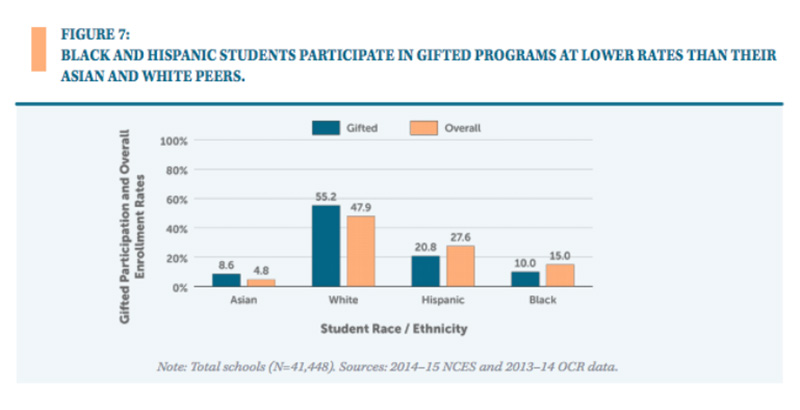

Additionally, black and Hispanic students are much less likely to be identified for gifted programs than their white and Asian peers. For example, although white students make up 48 percent of the national public school population, 55 percent are in gifted programs. But Hispanic students make up 28 percent of the population, and only 21 percent are in gifted programs.

The National Association for Gifted Children helps states develop legislation to improve gifted-education access. The goal is to remove the barriers that often prevent low-income and minority students from being identified and served, said Executive Director M. René Islas. For example, in Washington, some gifted testing takes place on Saturdays, which excludes families who don’t have the resources to bring their children to be screened, according to the Seattle Times. Ideal legislation allows multiple opportunities for testing, involves pushing for testing that is locally — rather than nationally — normed, and relies on more than recommendations from teachers, which can be biased, Islas said.

“I’m sure [opposition] has to do somewhat with the time and money that it takes, but I’m talking about social justice here,” Islas said. “It is the absolute right thing to do to create the opportunities for these children to be identified.”

Disclosure: Kate Stringer was a policy intern at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute in 2015.

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

;)