Van Cleef: There’s a Huge Gap Between How We Talk About Teachers & How We Treat Them. Some Ways to Make Teaching the Sought-After Profession It Should Be

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

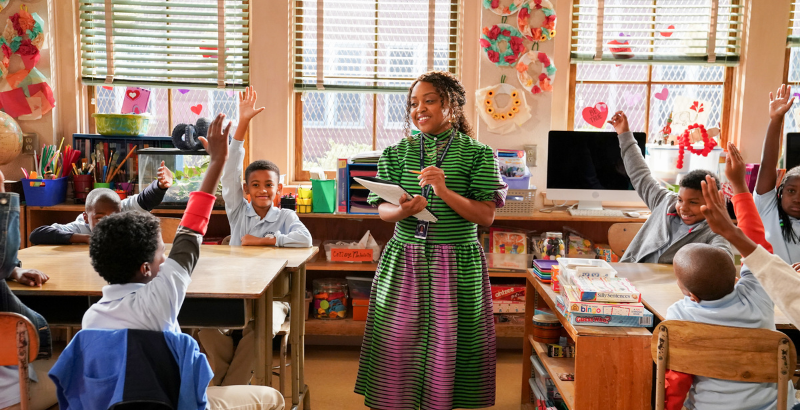

If you want to understand the teacher shortages disrupting schools across the country this winter, check out an episode of the new sitcom Abbott Elementary, which follows teachers at a fictional school in South Philadelphia. Like most successful comedies, the show is rooted in truth — including two chronic problems with the teacher job market that are fueling this year’s staffing challenges.

First, teacher shortages are nothing new — especially for schools that serve low-income communities, which have always had the fewest effective educators and the highest turnover. One character in the show is a substitute covering for a teacher who quit midyear, which was already a common occurrence in these schools before the pandemic. And many districts have long struggled to find teachers in key subjects like math and science, or to hire enough Black and brown teachers to close the diversity gap that research shows is so harmful to students.

But Abbott Elementary mines most of its humor from a second truth: the gap between how we talk about teachers and how we treat them. Watching its characters beg for supplies on TikTok or struggle with malfunctioning bathrooms shows that however much we revere teachers, their job seems tailor-made to drive away the newest generation of workers during the “Great Reshuffle.” Starting salaries for teachers are 25 percent lower than those in many other white-collar professions. Teachers have few opportunities to earn promotions without leaving the classroom. And many work in aging buildings without basic amenities you’d find in any office. This value proposition was never acceptable, but especially not in the current economy. It’s a big reason why even before the pandemic, more than 40 percent of teachers left the profession within their first five years, while thousands of people who earned teaching licenses never entered the classroom to begin with.

Leaders inside and outside education have let these issues fester for decades. Now, amid the added challenges of the pandemic, the bill for that inaction has finally come due. While the exact details vary from district to district, the themes my organization is hearing from the hundreds of school systems we work with are alarmingly consistent. Schools can’t find enough substitutes to cover absences. Many teachers are thinking of quitting; some are actually resigning. And fewer people are applying to fill the vacancies. There’s justified concern that beyond any shortages this year, not enough people want to be teachers next year and beyond. If they continue, these trends will have implications far beyond schools — because schools produce workers for every other industry. There are steps superintendents and principals can take right now to fill current teaching vacancies — and TNTP just released a new guide with specific ideas that can help. But districts can’t fix the root causes of these challenges alone. Addressing them requires coordinated action across the public and private sectors, and rethinking some fundamentals of the teaching profession.

First, make teaching accessible to more people. The main path to the classroom involves spending years and thousands of dollars on a graduate degree that many people simply can’t afford. Teachers in shortage areas like special education and bilingual ed often have to spend even more. It’s why states like Tennessee are forging partnerships among school districts, universities, labor unions and business groups to expand “grow your own” training programs for aspiring local teachers, which are more affordable and flexible than traditional education schools. Policymakers can also help by refocusing licensure rules on demonstrated teaching ability instead of paper credentials or standardized tests that set a less meaningful bar — and disproportionately screen out people of color.

Second, acknowledge that teachers, like all professionals, care about their pay and working conditions — and make teaching a better value proposition. States need to invest in more competitive teacher salaries from the very first year in the classroom, even if it means backloading less in pensions. School systems should create leadership roles that offer a career ladder and larger raises to successful teachers while they continue in the classroom. And districts need to prioritize building maintenance, school cultures and all the other elements of teachers’ daily working conditions.

Finally, reimagine the actual job of teaching. Asking lone teachers to meet the wide-ranging needs of an entire classroom of students on their own is a broken model: Not enough people want to do the job, and even fewer can do it well. But it’s not the only option for educating kids. School systems can leverage technology — for example, by creating video libraries of lessons to extend the reach of their best teachers, enabling novice educators to spend less time on planning and more time on individualized support for students. Arizona State University’s Next Education Workforce is going a step further by splitting teaching responsibilities across an entire team: a lead teacher who plans lessons, novices who deliver them and a cadre of paraprofessionals, specialists and community volunteers who provide extra help. Approaches like this would require support from entire communities to get off the ground but could bring many more talented people into the classroom.

The Omicron surge has magnified school staffing challenges rooted in issues that have festered for too long. If kids are to have the teachers they need to recover from the pandemic, and if communities and businesses are to have the workforces they need to thrive, we can’t wait another day. It’s time to take teaching from the object of sitcom jokes to the sought-after profession it should be.

Victoria Van Cleef is an executive vice president at TNTP, a national nonprofit that helps school systems across the country end educational inequality and achieve their goals for students.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)