Unjust ‘Deserts’: New Report Maps High-Poverty Areas Across America Where Parents Have No School Options

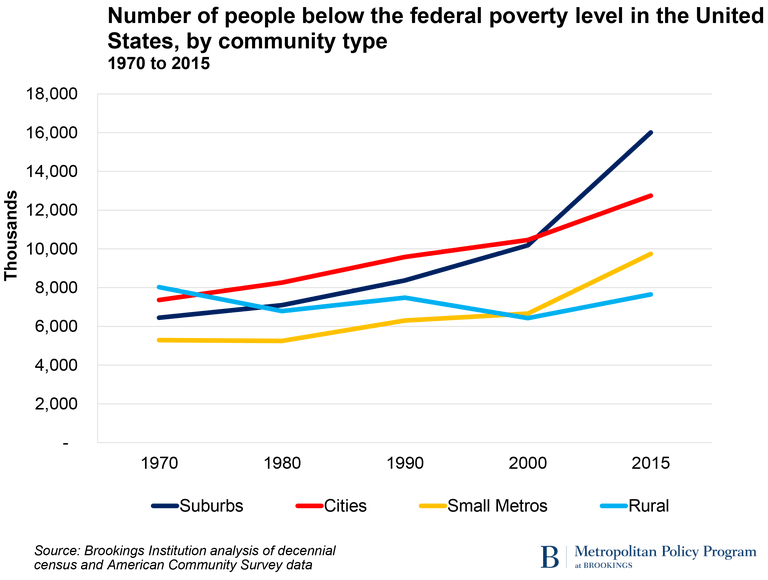

Poverty in America hasn’t just grown over the past 20 years; it has overflowed city lines. The suburban poor accounted for near half of the nation’s increase between 2000 and 2015, with more people in poverty now living in suburbs than in cities.

With charter school expansion stalled, a new report from the Thomas B. Fordham Institute suggests that part of the explanation may be that demand for charters has been largely satisfied in poor urban areas where these schools have long been concentrated.

“If so, perhaps it’s time to look for new frontiers,” say Fordham’s Mike Petrilli and Amber Northern in a foreword. “Are we overlooking neighborhoods in America that are already home to plenty of poor kids, and contain the population density necessary to make school choice work?”

Petrilli and Northern enlisted Andrew Saultz, a sociologist of education at Miami University, along with a team of his graduate students, to map every census tract in the country with data about schools — both traditional and charter — and poverty rates. About 50.7 million children attend U.S. public schools, including around 3.2 million in charters.

Focusing on the 42 states that have laws permitting charter schools, the report calls locations where three adjoining tracts have at least a 20 percent poverty rate and no charter elementary schools “charter school deserts” — also the buzzy title of the 130-page report (full title: Charter School Deserts: High-Poverty Neighborhoods with Limited Educational Options).

Fordham supplemented the text with an interactive map and website that allows users to zoom in on any of the more than 73,000 census tracts in the United States.

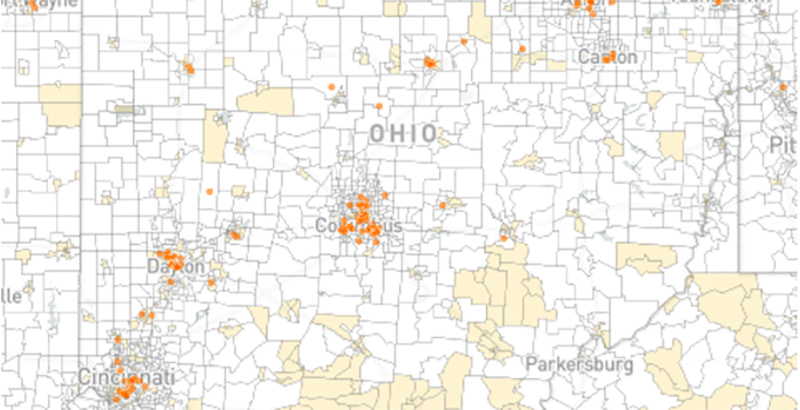

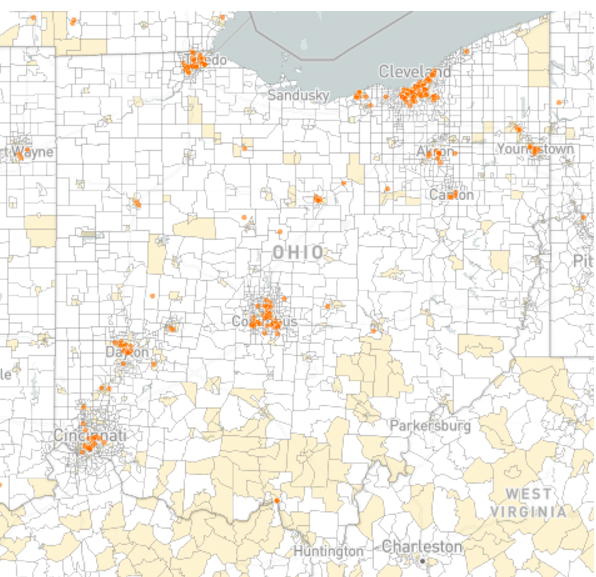

Saultz found that, as expected, charters are “overwhelmingly” located in and around cities. A total of 39 of the 42 states had charter deserts, ranging from one in Alaska (because most of the country’s largest state is uninhabited) to 34 in Ohio. Ohio has 360 charters, ranking 7th among states, but this image from the interactive map illustrates that they are clustered (as red dots) in a few of the state’s largest cities, including Cleveland, Toledo, Columbus, and Cincinnati. Pockets across the center of the state and broader swaths to the south are marked (in beige) as charter deserts.

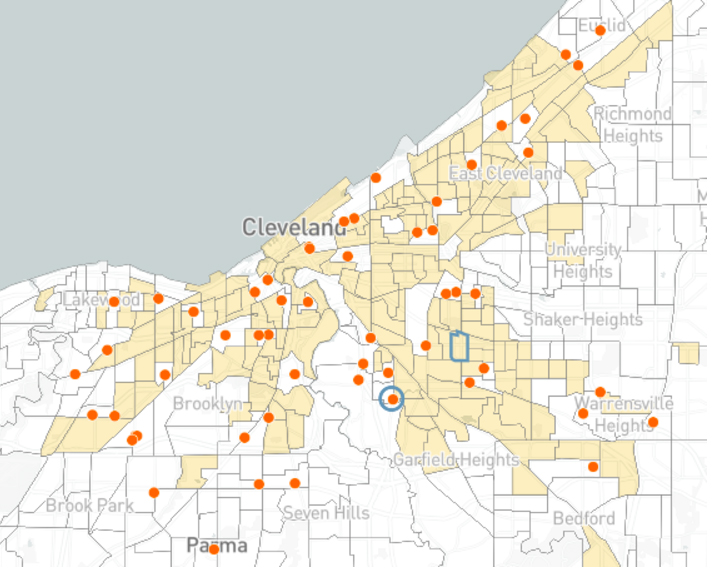

A closer look at Cleveland shows that even cities with multiple charters may have many poor areas considered deserts.

The report comes with self-described “limitations.” It doesn’t take into account state charter laws that limit how many and where charters may be built, or transportation, which may be prohibitively difficult even when a map suggests otherwise. Nor does it address the quality of schools — although the interactive site provides a recent year of charter achievement data.

In addition, some areas designated as deserts may be “very thinly populated” and unable to support a school, according to the report.

The absence of school quality data seems telling: it means that if a charter exists, however ineffective, the surrounding area isn’t considered a desert. And it means no matter how strong a traditional school in a poor area may be, if no charter is close by, education there is deficient.

Northern said Fordham had hoped to build in more nuance by including student growth measures but couldn’t get the necessary data.

“What we had originally were quality charter school deserts and just charter school deserts,” she said. “We were going to come up with some definition of what a quality charter school should be, but we were concerned with making urban charters look worse if we weren’t able to control for student demographics.”

There are other bugs. College towns are likely to be described as charter deserts, but only because their poverty rates are misleadingly elevated by the towns’ student populations.

Finally, while some charter operators may begin to look outside poor inner-city neighborhoods to the failing suburbs, some still see untapped opportunities close at hand.

“Demand remains high overall,” said James Merriman, CEO of the New York City Charter School Center. But he notes that many schools’ approaches have shifted over time in ways that may be a corollary to Fordham’s emphasis on flexibility and finding new locations with unmet needs.

“Part of the story of the charter sector has been an evolution from creating programs to which kids must fit to ensuring that your program is a good fit for kids,” he said. “It’s not as if there weren’t schools always doing that, but as a general trend there has been a greater focus in ensuring that your program meets children” rather than asking children to conform to the program.

“I think that’s a natural maturation of the sector.”

One city where charters are looking toward the suburbs is Denver. Kimberlee Sia, CEO of KIPP Colorado, said the network is “actively engaged in the process of expanding” as the city becomes more affluent.

“Denver is undergoing an incredible amount of growth and change, which has resulted in, among other things, higher cost of living and a major shortage of affordable housing. We know that many families are simply being priced out of Denver and are moving to the suburbs and surrounding areas,” she said. “A growing number of our current families now live outside of Denver, and many have expressed their desire for a KIPP school in their new neighborhood.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)