Their Backs Against the Wall: Small-City School Districts Like Providence, RI, Reopen With Aging Buildings, Few Resources

Just over a year after a devastating report by Johns Hopkins University indicted Providence public schools for low academic standards and unsafe buildings, the district has launched a hybrid reopening model amid all the familiar worries of COVID-19 — ventilation, social distancing and testing.

The 24,000-student district’s woes may be higher-profile than most thanks to the Hopkins report, but with students and teachers back in their classrooms since Sept. 14, Providence now walks the same thin line as many other small and medium-size public school systems. Should the district prioritize the academic and social well-being of its student population, which studies suggest may be disproportionately hurt by remote learning, or the physical health of students and staff by avoiding the hazard of facilities that have seen decades of neglect?

The answer is that Providence will somehow need to do both.

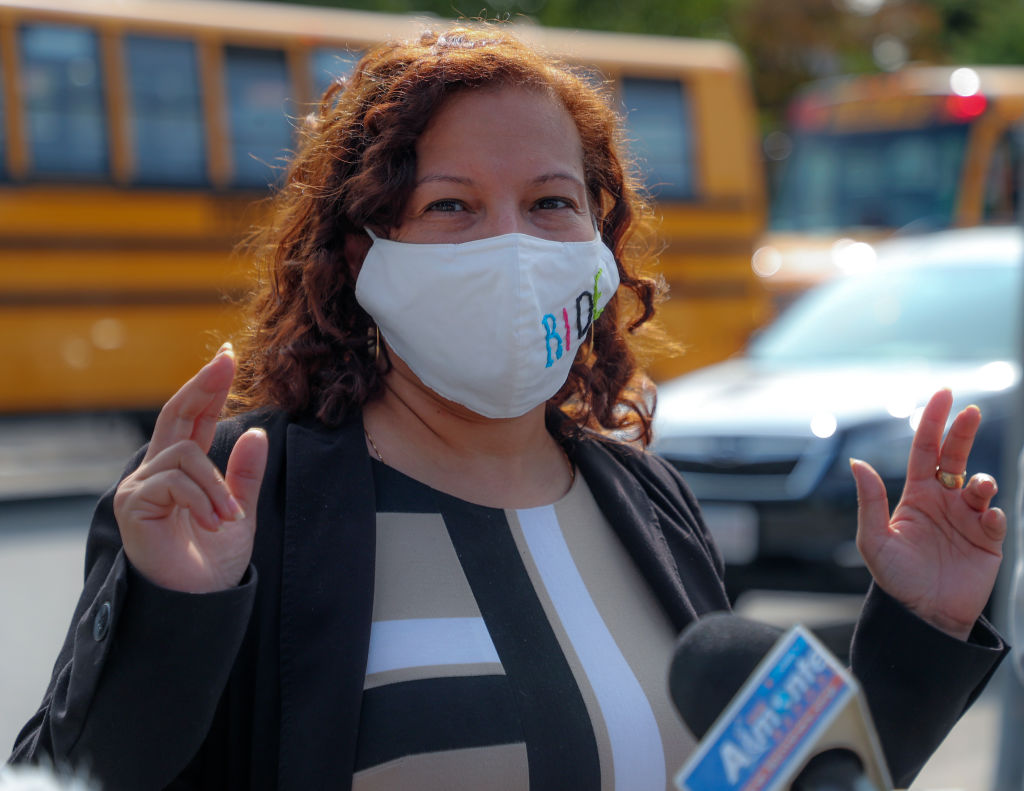

“We’re willing to do whatever it takes to make sure that people feel safe, that their kids get an education,” Rhode Island Commissioner of Education Angélica Infante-Green, who took charge of the district last year after a state takeover, told The 74. “We were already behind the 8-ball, we know that.”

Providence, like many of its small-city counterparts foraging for revenue streams even before the pandemic, will have to manage this difficult balance with limited funds.

“Small-city school districts tend to have older facilities,” explained Andrew Van Alstyne, a co-author of a 2018 report on resource gaps in small-city school districts. So as these districts try to adapt to the pandemic, “they’re doing this with their backs already against the wall.”

The 2019 report from Johns Hopkins University researchers on Providence schools found that “[the city’s buildings] are crumbling, there’s mold, there’s water coming into the building.”

“We don’t need to be told in Providence that we’re struggling. We know we’re struggling,” said Providence high school teacher Maya Chavez.

For many teachers, fixing Providence’s schools is a matter of equity. Eighty-four percent of the children the district serves come from low-income families, and 91 percent are students of color. If Providence schools fail to effectively mitigate the risks of the virus, it will be historically marginalized students who bear the brunt of the consequences.

“If we don’t have the resources, then we need to demand that those resources are made available. We can’t just accept this idea that Providence kids are going to be less safe … and less healthy, and less cared for than kids in other districts,” said Chavez.

Providence schools have undergone a partial reopening, thanks in part to statewide enthusiasm for in-person learning spearheaded by Rhode Island Gov. Gina Raimondo. Elementary students are back for full in-person learning, while middle school students and high school freshmen alternate between days of in-person and remote instruction. Most other high school grades are still primarily remote, and districtwide, 6,500 students opted out of in-person learning entirely, signing up for a remote option through the first semester.

In response to the virus, Providence has upped its efforts to ensure safety. All summer, the district was working to update school facilities, and each of the district’s 38 buildings has a plan to maintain good air quality. For sanitation, the district now has 60 percent more custodians on staff than last year.

“We know the buildings are aging. … But that does not make the buildings unsafe for COVID,” said Infante-Green.

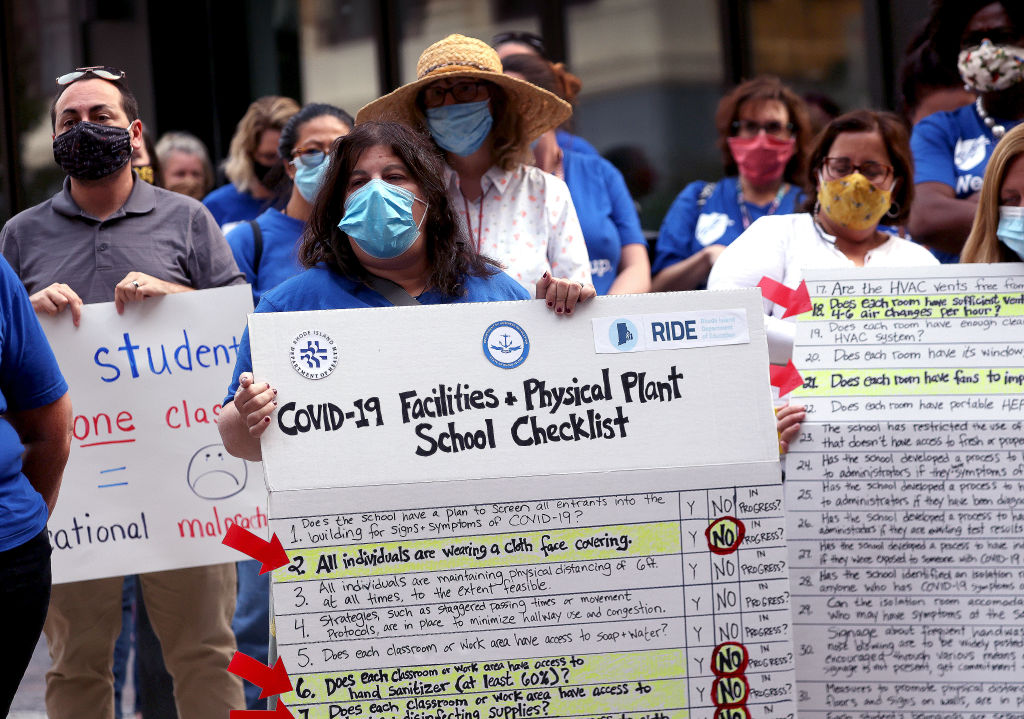

But some teachers aren’t so confident. Many buildings have windows that are painted shut and will not open (though the district said these classrooms have been equipped with air purifiers). Multiple teachers told The 74 that even during in-service training this September, their HVAC systems didn’t function properly. When the district released the results of its school-readiness walk-throughs before opening, a number of schools had essential safety measures marked incomplete.

There are “major, major problems that are slipping through the cracks and going unnoticed,” said Chavez.

Chavez and a number of other teachers have been outspoken in their efforts to call attention to these issues. They have taken to Twitter posting photos of safety hazards in their classrooms. A week before the district reopened, the Providence Teachers Union staged a protest on the statehouse lawn setting up a mock classroom to demonstrate just how cramped their buildings would be.

‘I miss learning’

Commissioner Infante-Green hopes staff will unite and direct their focus on the task ahead. “Right now we’re fighting a pandemic, and we should be working together to get our kids ready and to be front and center,” she said in a press conference after the Providence Teachers Union announced an appeal to the National Institute for Occupational Health and Safety for a districtwide facility review.

Even during a pandemic, the district has implemented a number of measures to promote student success. It invested in a new K-8 curriculum, expanded teacher professional development, created algebra tutoring options for all ninth-graders, and rolled out college dual enrollment opportunities for high school seniors. This week, seniors also returned to their buildings for half days, in part to prepare for the college application process.

Still, in majority-low-income districts like Providence, there’s reason to believe that the most important move of all may simply be the safe return to in-person learning. Initial research on the effects of COVID on education finds that remote learning disproportionately hurts low-income students, who may be less likely to have reliable internet, quality devices and a room free from distractions. Many Providence students are grateful for the chance to be back in the classroom.

“I miss learning,” said Ghana Alnmes, a sixth-grader who immigrated to Providence five years ago with her family as refugees displaced by conflict in Syria. Alnmes is a star student: Even while honing her English language skills, she earned a spot in her middle school’s gifted and talented program. But even for her, remote learning was difficult this past spring.

“If you’re online, you just open the computer, and press on the meeting, and just, like, go to sleep or something,” she said. Most of the kids “really don’t do anything or listen to the teacher.” When she herself was tired, she would record the classes to watch later, Alnmes was quick to note. She’s glad to now be back for in-person learning at least part of the time.

Michellette Brand, a high school senior in Providence, has also had difficulty with remote learning. She attends a charter school that opted to start the year fully online. During the school day, she regularly has to tend to her two younger brothers. “My house is actually really loud. So it’s very stressful to be in a house that’s very loud, that you can’t really control. Because I can’t focus on school work,” explained Brand.

But even though she recognizes the benefits of in-person learning, Brand has been upset with the way Providence has gone about its reopening. She is a leader in the Providence Student Union, and she has joined multiple conversations with district officials that were billed as opportunities for students to share their voices, including one meeting with the commissioner the week before schools reopened, but she doubts whether students were taken seriously.

“It’s kind of like we’re just not being listened to,” said Brand. “It’s kind of like they host these meetings and conversations just so they can be like, ‘Hey, look, we are listening to you.’ But it’s kind of just like for show. It’s not really for action.”

Still, Brand hopes that the district will be real about the challenges and dangers of COVID. “This isn’t something that you can sugarcoat. It’s a serious issue,” said Brand.

‘Are they going to tell us if there’s COVID in the classroom?’

For Providence high school teacher Cindy Castellone, the dangers are personal and threatening. She is the primary caregiver for her husband, who is recovering from heart surgery, and she has additional health complications herself. She filed an application to teach in the district’s Virtual Learning Academy, a remote learning option for Providence students, but her request was denied. Later, she heard that some teachers had received Virtual Learning Academy placements even though they preferred to teach in person.

Via text, Providence Teachers Union President Maribeth Calabro confirmed what Castellone had heard but explained that “folks are fearful of speaking out due to retaliation.”

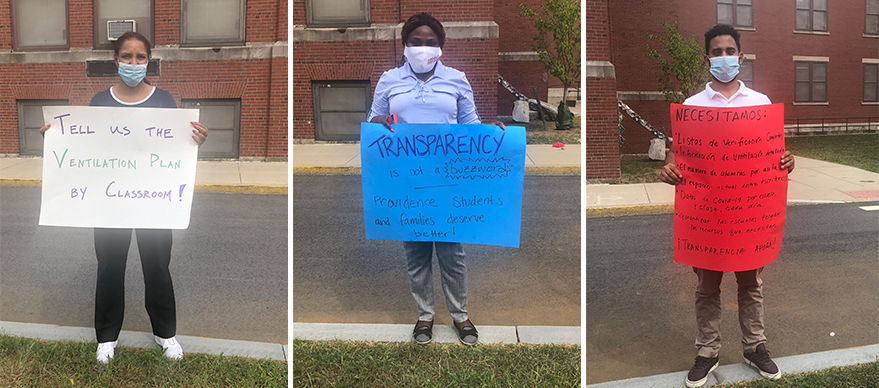

“The lack of transparency has been really quite horrifying,” said Castellone.

Parents in the district share Castellone’s frustration. Toting signs reading “You Promised Us Transparency. This Isn’t It” and “Tell Us the Ventilation Plan by Classroom,” a group of parents representing 11 Providence schools protested the lack of communication in the lead-up to reopening.

“They give us a note if there’s lice in our classroom. Are they gonna tell us if there’s COVID in our classroom? Are they gonna tell us if there’s COVID in the school?” said Jenna Karlin, one of the parents who took part in the protest.

Herself the symbol of institutional power in the district, Commissioner Infante-Green empathized with their concerns. “There’s distrust in Providence, period. I think they have been let down for a very long time, so anything that anyone says, their first instinct is not to trust.”

But amid fear and skepticism, health experts are optimistic about the measures that Providence schools have put in place.

“We’ve really set up a robust approach to addressing COVID in the K-12 school system,” said Dr. Philip Chan, associate professor of medicine at Brown University and medical director for the Rhode Island Department of Health. Any student or staff member who is symptomatic or has been exposed to someone who tested COVID positive will have access to free, rapid-results testing. “We are really leading the way in this,” said Chan. “I think we’ve set a model for other places.”

As of Sept. 28, across Rhode Island, there had been 33 positive cases identified among in-person students and staff and 44 positive cases identified among virtual learners, said the state department of education. According to Chan, those results actually represent the successful interruption of the chain of transmission in schools. “That was what the system was designed to do,” he said.

But as strong as Providence’s safety measures may be, the task ahead for the district will be anything but easy. Notwithstanding the many uncertainties and even with district critics, there is still a shared sense of purpose and commitment to the city’s students.

Karlin, the parent of two elementary students, has confidence in the school environment her children enter each day. “The leadership of the school, the teachers, the aides, right, I think everyone there is really excited to see them and will give them … a warm and caring and steady environment,” she said.

High school teacher Chavez, while demanding changes for her students, knows that the path forward will take work on all sides.

“I’m not here to call Providence out. I’m here to call Providence in.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)