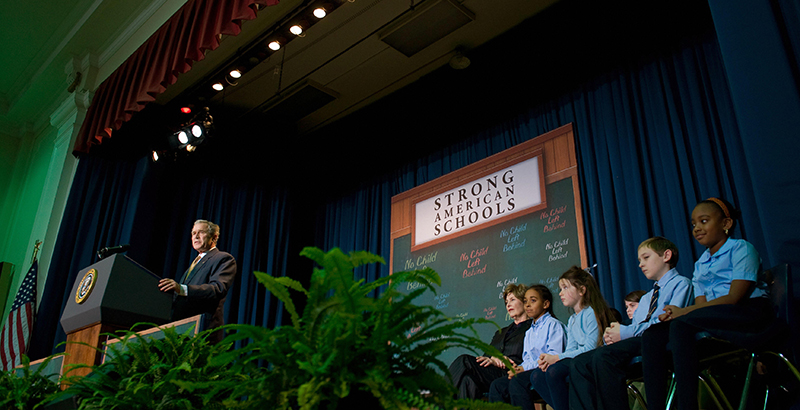

‘The Soft Bigotry of Low Expectations,’ Still Alive and Well 16 Years Later? An Insider Looks Back at the Legacy of No Child Left Behind

The signing into law of No Child Left Behind 16 years ago this week seemed like a sea change at the time. In many ways, it was, and I had the privilege of playing a bit of a unique role with the bill. During its creation, I worked on Capitol Hill for a leader on the Senate Education Committee. Then, after its passage, I moved to the White House and the U.S. Department of Education to work on implementing NCLB.

I still hear lots of comments that the law failed. An equal number of parents and educators tell me that it brought about a focus and high aspirations that had never been in place. Like any piece of legislation, the truth sits somewhere in the middle.

From a systems perspective, NCLB brought about significant policy changes that remain in place. The annual assessments that have been decried for years are still there. Breaking apart testing data by race, income, and special education status is still required. And states still must have accountability systems to move all students toward grade-level performance in math and reading, even if the requirements of those accountability systems have changed.

One of the most important breakthroughs is the commonplace expectation that we will have regular disaggregated data. It seems hard to envision that we’ll ever go back to aggregating data and focusing solely on the performance of the whole school.

We’ve also come a long way with every state having standards and criterion-referenced assessments in place. It’s almost hard to believe that states were often using norm-referenced tests prior to NCLB and were hoping to keep those in place, instead of using assessments aligned to state standards. Now, criterion-referenced assessments are the norm in every state and go beyond just grade-span tests.

The ultimate aim of having more kids reading and doing math proficiently, especially low-income and minority children, started to move in the right direction, too. In 2000, 35 percent of black students scored at basic levels in reading on the National Assessment of Educational Progress test; by 2009, that figure had increased to 48 percent, and today it stands at 52 percent. Similar improvements were seen for Hispanic students, special education students, and low-income students, and gains were generally even higher in math. Those are no small feats.

But we have also fallen short in many ways. For example, state standards and assessments still have room for improvement. While most states have increased their academic proficiency standards, states like my current home state of Texas are moving in the wrong direction.

Texas’s standards are low, and the state continues to play games by setting low expectations for how many questions a student has to get right on the state assessment. Performance appears to be getting better, but in actuality the bar is just being lowered.

Nationally, while student achievement started to move in the right direction in the 2000s, we have seen either flattening achievement or, in some cases, declines since that time. The most recent results from the Program for International Student Assessment administered in 2015 show that the U.S. has fallen 17 points in math and six points in science from 2009 to 2015. The percentage of eighth-graders scoring at or above basic in reading on the NAEP has been stagnant, and we have seen declines in math in the most recent results from 2015.

Despite that bad news, we get a lot of yawns in reaction to the data and a sense of complacency has set in. Flat or declining achievement used to get the attention of policymakers and the public. Now there’s not much of a reaction and not much of a sense of urgency in changing the status quo.

That complacency is also still alive and well in what President George W. Bush called “the soft bigotry of low expectations.” A recent study by Seth Gershenson of American University and Nicholas Papageorge of Johns Hopkins University followed students who were in 10th grade in 2002 through to 2012. They found that white teachers on average had significantly lower expectations for black students than they did for white students.

The study also showed that those lower expectations impact achievement; having teachers who were confident that their students would complete college made a real difference in their college attainment. Setting high expectations for students cannot solely be done through legislative action, but No Child Left Behind certainly had that aspiration, whether people liked it or not.

It mattered that we had a president and leaders in Congress talking about and fighting against that soft bigotry of low expectations. We can’t prove causality, but seeing increases in student achievement for minority students after passage of the law seems likely to have some correlation.

We’ve come a long way, but have a long way to go. That kind of national leadership and sense of urgency are needed now more than ever.

Holly Kuzmich is executive director of the George W. Bush Institute.

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

;)