The Opioid Crisis Was America’s Epidemic Before COVID. Research Suggests that Overdoses Hurt Student Achievement

Long before the emergence of COVID-19, the United States was struggling to contain a years-long opioid crisis that took tens of thousands of lives every year. Now, with Oxycontin manufacturer Purdue Pharma still negotiating billion-dollar penalties for its role in the two-decade drug epidemic, experts have begun taking the measure of its impact on student learning.

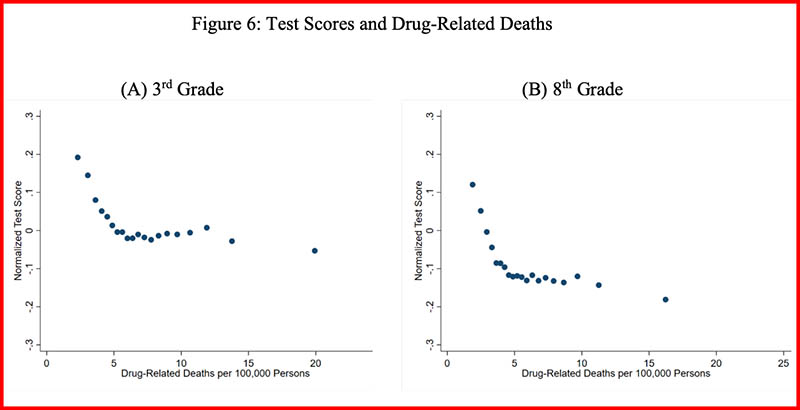

In a working paper released last November, researchers found persuasive evidence linking fatal overdoses around the country to lower test scores for students in hard-hit counties. The trend is particularly pronounced in rural communities, which have been especially ravaged by the spread of ultra-addictive substances like heroin and fentanyl.

Rajeev Darolia, a professor of public policy at the University of Kentucky and one of the study’s authors, said in an interview that children living in areas battered by successive waves of narcotic abuse were twice-afflicted — not only by the stress caused by deaths in their homes and neighborhoods, but also by the lack of public resources required to mitigate it, such as drug counseling and mental health clinics.

“Vulnerability to the epidemic is critical, and I think this is where schools and institutions can play a bigger role,” Darolia observed. “What’s potentially most concerning about these [heavily affected] counties and districts is that they are both likely to have high exposure, and the kids are likely to have high vulnerability as well. The combination of those things…is worth paying more attention to.”

Darolia and his co-author, Brown University professor John Tyler, studied student achievement by gathering nationwide test scores from the Stanford Educational Data Archive. To illustrate the regions where opioid use claimed the most lives, they used county-level statistics on drug-related mortality from the University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation between 2009 and 2014.

Drug-related deaths have been consistently heading upwards since the 1980s, but that five-year span saw a confluence of multiple phases of the unfolding opioid emergency. In response to the abuse of prescription painkillers like oxycodone, medical authorities began instituting more regulatory controls, and users instead resorted to synthetic alternatives like fentanyl.

The researchers found that higher exposure to deadly overdoses — as measured by average drug-related mortality rate in a given county during a student’s lifetime — was associated with significantly lower test results among both third- and eighth-graders. That relationship was especially evident in opioid hot-spots across Appalachia, the Southwest, and the West.

While test scores in rural counties are typically lower than those in their urban or suburban counterparts, that differential grew as county-level deaths due to overdose increased. And large gaps existed even among otherwise-comparable areas: In rural counties at the 90th percentile and above for drug-related mortality, test scores were vastly lower than in rural counties in the bottom 10 percent.

Darolia cautioned that establishing ironclad causal evidence for an opioid-academic link was an empirical challenge, mostly because counties with high levels of drug abuse and overdoses are also plagued by a wide variety of social disadvantages, from lower employment rates to higher crime and a lack of access to healthcare. But the pattern of lower performance on standardized tests was consistently borne out in opioid-affected communities even when controlling for economic and demographic factors.

The study is the latest evidence pointing to the significant negative impacts of environmental stress on children’s educational prospects. Previous research has demonstrated that students score lower if they live in neighborhoods with higher amounts of violent crime or police shootings. Elevated rates of opioid abuse have also been linked with lower labor force participation and more children being removed from their homes.

And while Darolia and Tyler restricted their study to the years leading up to 2014, there is reason to think that matters have only gotten worse over the last half-decade. Over 80,000 Americans died of fatal overdoses in the 12-month span preceding May 2020, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Economic damage and social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic seems to have exacerbated the problem, with 10 western states reporting increases in synthetic opioid-related deaths exceeding 98 percent.

More research will be needed to isolate the consequences of escalating drug mortality on academic outcomes at all levels. Darolia is currently working on other projects to assess the social costs of the drug crisis, including one that aims to study the effect of legislation in Florida shutting down “pill mill” pharmacies. He said that he worried that the damage wrought by COVID on state and local health systems had already deepened those costs to a degree that isn’t fully understood.

“In states like the one where I live [Kentucky], I have a ton of concern about the stress that COVID is putting on systems that are also trying to address the opioid epidemic. It’s not as though, just because everybody’s paying attention to COVID right now, opioid use is getting better; it’s likely getting much worse, we’re just paying less attention to it.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)