The National Math and Science Initiative Has Poured $52M Into Expanding AP Courses for Students Whose Families Serve in the Military. Here’s Why

A few years ago, Bellevue West High School in Nebraska was trying to address two challenges.

First, with the school just three miles from Offutt Air Force Base, about a quarter of its roughly 1,600 students had parents who serve in the military. These students tend to be highly mobile — on average, children in military families move six to nine times during their school career — and, despite the widespread adoption of the Common Core State Standards, there is still significant variation across states in what is taught and when.

Second, the school’s Advanced Placement program had become restrictive, with students and their parents having to petition the staff to enroll. Given their rigor, AP courses are critical to winning admission to certain selective colleges and are seen as helpful preparation for college-level work. They can also result in college credit, saving students precious money and time.

“We were doing a lot of gatekeeping,” said Fran Pokorski, one of the school’s assistant principals. “We were looking for the 100 percent college-ready kid. There were so many other kids who we didn’t invite to be a part of these experiences.”

Then school officials heard about a grant from the National Math and Science Initiative, a STEM-focused nonprofit, that promised to simultaneously address both riddles through a dramatic expansion of the school’s AP program. AP courses cover the same content and generally proceed at the same pace regardless of what state they are taught in, which make them ideal for students from military families who might be moving mid-school year. Plus, if they score high enough on the end-of-course test, students can earn that college credit.

Bellevue West and its sister school received a three-year, $1.3 million grant, which helped them double their number of AP classes and allowed students who had never taken an AP course to enroll.

“It’s a great problem to have,” Pokorski said of broadened student interest in the AP program, which grew from 404 to 695 seats. “But now we’re like, ‘How do we accommodate all of the kids who want to take the [AP] exam?’”

The grant Bellevue West received is part of the National Math and Science Initiative’s Military Families Mission, a program primarily funded through contributions from the Department of Defense as well as corporations like ExxonMobil and Boeing and organizations like the College Board itself, the nonprofit that runs the Advanced Placement program.

By expanding access to AP courses, the program aims to smooth students’ transitions during high school and prepare them for more challenging jobs, which may well end up being in the military. About 80 percent of troops come from families in which at least one sibling, parent, grandparent, cousin, aunt or uncle has also enlisted, according to Pentagon data. By focusing on students with those family ties, the program is also supporting military readiness.

“We’re trying to encourage kids to step up and look at the heavier-lift jobs,” said Ed Veiga, senior director of the Military Families Mission. “It’s about kids having computer science skills, for instance, kids having a background of rigorous math skills. There’s just such a huge need across the country.”

Program officials estimate that around the country, there are more than 300 military-connected schools — defined as schools with at least 100 students who have one or more parents on active duty — and since its launch in 2011, the Military Families Mission has reached more than 250 of them.

In focusing on expanding AP access to schools that serve military-connected families, the Military Families Mission is also advancing an equity goal. The military is slightly more racially diverse than the nation at large, and the racial demographics of the nearly 34,000 students enrolled in AP classes at military-connected schools that NMSI works with are slightly more diverse than the students who take AP exams nationwide.

The College Board has demographics on the students who sit for the final test nationally, but not on the students who simply enroll in an AP course, although the classes are generally geared toward getting all enrolled students to take the AP test and do well on it. Those outcomes vary widely by race. In 2017, only about 30 percent of exams taken by Black students and 42 percent of exams taken by Hispanic students received a passing score, compared with 64 percent of exams taken by white students, Chalkbeat reported.

Staff from the Military Families Mission work with each school to set participation goals to help ensure diversity in AP course enrollment.

“We always want to be part of a positive force for kids farthest from opportunity,” said Veiga. “Racially, ethnically, we need more diversity in the STEM workforce. And we help the schools look at that.”

The Military Families Mission program has contributed more than $52 million to participating schools, which is primarily allocated in three ways.

One bucket of money defrays the amount that students have to pay for each end-of-year AP test, cutting costs from $94 per test to $36.

Another bucket is the reward money students and teachers receive. AP tests are scored on a 0-5 scale, and colleges typically award credit for scores of 3 or higher. At participating schools, students receive $100 for each qualifying score, and so do their teachers. Pokorski said individual teachers have earned as much as $6,000 a year through these performance bonuses, notable in a district where the starting salary is $35,772.

The third funding area is teacher training. At Bellevue West, for instance, the budget for professional development was only large enough for one teacher to attend an AP conference each year. With the grant, more than 60 of Bellevue West’s 100 teachers have attended the conference in the past two years. Nationwide, the Military Families Mission has funded training for more than 11,700 teachers.

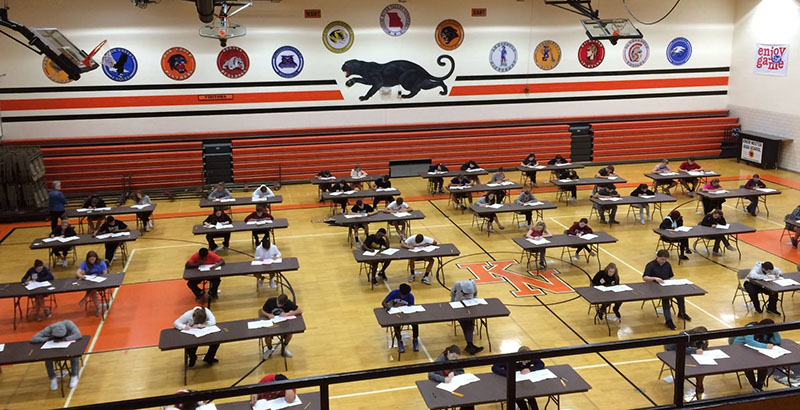

At Knob Noster High School in Missouri, nearly 70 percent of the school’s 375 students have parents who serve at nearby Whiteman Air Force Base, home of the B-2 bomber. The school did not offer any AP classes in 2015-16, before it received the grant from the National Math and Science Initiative. For the 2018-19 school year, Knob Noster offered 12 different AP classes, and 180 students enrolled.

Part of the reason students have taken to the program so quickly, said Jerrod Wheeler, a third-generation Missouri school superintendent who oversees Knob Noster, has been their parents’ support.

“These [military] parents and families have been all over the world — from Ramstein, Germany, to Fairfax [Virginia], to you name it,” he said. “They come in with the expectation that we should offer these robust, advanced courses. So it’s been a pretty easy sell for us.”

One Knob Noster parent, Tim Moreland, a retired Air Force senior master sergeant, said his older children attended schools in two different countries and two different states. One of his sons recently graduated from the University of Central Missouri a semester early because of the college credit he earned by taking AP courses in high school, and Moreland is glad that the more academically advanced courses have been available to his children.

“You have to challenge them,” he said. “You have to give our children the chance to excel in life.”

Moreland’s daughter, Jenna, a junior at Knob Noster, is taking two AP classes this year, and she plans to take two more her senior year. She called the $100 she could receive for each qualifying score on the AP tests “that extra cherry on top” but said the money was not why she enrolled.

“My motivation was I needed something harder. I needed a harder curriculum,” she said. “Like, even in middle school, I was like, ‘K, there’s Advanced Placement classes at high school. That’s what I need; that’s what I’m working towards.’”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)