The Children Left Behind By 1 Million U.S. COVID Deaths

By Asher Lehrer-Small | April 24, 2022

Nearly 250,000 youth have lost a parent or caregiver to the virus. But some parents say schools aren’t adequately reckoning with the fallout

Updated, May 12

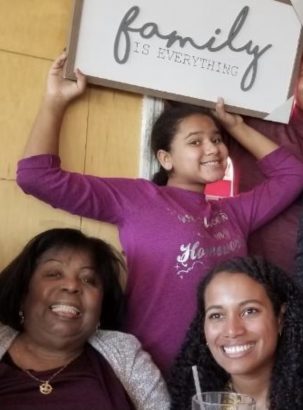

Just 10 years old at the time, it was as if Eva Torres’s world fell in when COVID claimed the life of her grandmother in April 2020.

Abuela, as the girl called her, had lived just a block from the Bronx apartment she shared with her parents and two older brothers. Grandma was the one who would pick her up from school each day and “hear her 10,000 stories,” said Eva’s mother Angela Torres, “even if she was repeating it for the 20th time.”

After Eva’s grandmother passed, the elder Torres watched her daughter’s grades slip. Her once-bubbly girl seemed withdrawn, weighed down by anxiety.

“[That kind of loss,] it’s something that you carry with you,” the mother told The 74. “It permeates into your very soul.”

The Torres children are three of the 8,649 youth in New York City believed to have lost a parent or caregiver to COVID. That’s roughly equivalent to the entire child population of Manhattan’s Battery Park/Tribeca district — or 1 out of every 200 youth in the entire city.

The U.S. reached 1 million recorded COVID deaths this week, a grim and once inconceivable milestone. President Joe Biden on Thursday ordered all flags on government buildings to fly at half-staff for five days.

“One million empty chairs around the dinner table,” Biden said in a statement. “Each leaving behind a family, a community, and a nation forever changed because of this pandemic. … [Americans] must not grow numb to such sorrow.”

Yet with almost 250,000 youth nationwide having experienced the loss of a caregiver to the virus, some parents say schools aren’t adequately reckoning with the fallout for bereaved students.

“We don’t talk about the people we’ve lost. That conversation is completely not occurring,” said Brooklyn mother Melissa Keaton.

Two years after the April 2020 death of Keaton’s father who lived with the family in their Flatbush apartment, Melissa’s daughter, Melanie, still mourns the loss of her grandfather. The 9-year-old used to end each evening by calling out, “Goodnight, Papa.” Now the missing ritual provides a daily reminder of his absence, said Keaton.

“With grief, there’s no time limit,” explained the mother.

Though much of the nation is eager to put the pandemic in the rearview mirror, life will never return to a pre-pandemic normal for children like Melanie who have endured the trauma of losing a loved one, said Keaton.

That’s a reality educators are now forced to contend with. On average in the U.S., each school serves two children who lost a parent or caregiver to COVID.

In New York City, which became the global epicenter of the pandemic in spring 2020, the issue is even more acute. Many schools in neighborhoods that were hard hit by the virus now serve over a dozen students who lost a caregiver during the pandemic, school social workers told The 74. Researchers said they fear the number in some schools may be of a much higher magnitude, as many as 100.

The New York City Department of Education did not provide an estimate confirming or denying those figures.

In the city’s high-poverty, predominantly Black and Hispanic neighborhoods, which suffered disproportionate COVID deaths, it became difficult to track and absorb the losses during the harshest moments of the pandemic, said Ilka Rios, a Bronx public school parent.

“Daily, I would log into social media and it was ‘Rest In Peace,’ ‘Rest In Peace,’” she said.

Racial disparities in caregiver loss have been more pronounced in New York City than in the rest of the country, with Black and Hispanic children experiencing the death of a parent or caregiver at 3.3 and 2.6 times the rate of white NYC children, respectively. Nationally, Black and Hispanic children also suffered greater loss than their white peers, but the difference was less dramatic, at 2.1 times.

The 8,649-youth total itself is likely an undercount, said University of Pennsylvania researcher Dan Treglia. The COVID Collaborative, for whom Treglia did the work, provided the tally of COVID-bereaved children to The 74, derived, he said, by combining the city’s coronavirus death numbers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention with household-level data from the 2019 American Community Survey.

“These estimates are a lower bound,” said Teglia. “Because New York City was hit so early, we were still figuring out how to recognize and code COVID-19 deaths.”

‘Slipping through the cracks’

But as the city continues to grapple with the fallout, advocates fear that governmental systems are ill-equipped to identify the young people left behind.

“We don’t know who these children are,” said Catherine Jaynes of the COVID Collaborative. “There’s no systematic way to identify them.”

The nation’s largest school district has no internal mechanism letting them know when a student experiences the death of a loved one. Death certificates do not list whether deceased individuals were a parent or guardian and no agency, as far as representatives for the Department of Health were aware, cross-checks records to identify bereaved children. Instead, the onus to let teachers and school leaders know of a recent loss falls on the grieving family.

“We are alerted to a death in the family by other family members or people who are close to the family,” said DOE Press Secretary Nathaniel Styer in an email.

Teachers ought to be aware of the circumstances students are going through, said Nkomo Morris, a counselor at Harvest Collegiate High School in Manhattan.

If you know a student has recently experienced the death of a family member, “you’re not going to be like, ‘Why are you late to class?’” she said. “You’re gonna pay more attention to them, you’re going to be a little sweeter to them.”

When students at her school experience trauma in their outside lives, it gets recorded in an internal system called JumpRope, which automatically sends an email notifying the student’s teachers and counselors, said Morris.

But on other campuses, the response is less streamlined. Danielle Shapiro-Nussen works as a special education teacher at a District 75 school in the Hunts Point section of the Bronx and suspects there may be students who have experienced the death of a caregiver without the school becoming aware.

“It’s possible that some of these families have gone through a tremendous loss … and we don’t know,” she told The 74. “Unless a family member said, ‘Yes, we lost a [loved one],’ there’s probably no way we would have known.”

“I think there are thousands of children who are slipping through the cracks,” said Ayana Bartholomew, a former program officer overseeing efforts to support COVID-bereaved children at the Robin Hood Foundation who left the organization in mid-April.

A bill introduced mid-April in the City Council seeks a more complete accounting, requiring the Administration for Children’s Services to produce quarterly reports on the impact of the death of parents or caregivers dating back to January 2020.

The country as a whole has not done enough to account for the “downstream consequences” of caregiver loss through the pandemic, said the Collaborative’s Treglia.

Bereaved youth have higher rates of depression and post-traumatic stress disorder than those who have not lost parents, he pointed out. They are more than twice as likely to show impairments in functioning at school and at home, even seven years later, meaning these children need both immediate and long-term counseling and support to deal with such a traumatic loss.

President Joe Biden used an April 5 memo to draw attention to the long-term effects of COVID, including the fallout for young people who lost caregivers, but the announcement “doesn’t outline any plan or commitment,” Rachel Kidman, a social epidemiologist at Stony Brook University, says in a recent article in The Atlantic. Although the administration has disbursed some funds to grieving families, including to defray funeral costs and for mental health supports, “no law or executive order has provided any resources specifically for pandemic orphans,” the story points out.

Supporting COVID-bereaved families

The COVID Collaborative’s Hidden Pain report calls for a more robust nationwide response.

“We recommend a White House Executive Order to provide for screening (for COVID-related caregiver loss) in public and publicly subsidized schools, early childhood education and healthcare settings, along with public-private partnerships to facilitate screenings in other circumstances,” the authors write.

No such program yet exists, but on a smaller scale, efforts have cropped up to identify and provide aid to those who lost a caregiver to the virus. Montefiore Health System launched its “Family Resiliency Program” in 2020, combing through medical records to identify New York City and Lower Hudson Valley households with children that lost a parent to COVID. By filtering COVID deaths by age and cross-checking the notes recorded by health care workers, such as whether nurses helped the patient FaceTime loved ones, the initiative reached 475 families.

“It was a heavy lift,” admitted Deirdre Sekulic, assistant director of social work at the Bronx hospital, who personally made many of the phone calls to eligible households.

“Lots of these were families that were kind of OK before the pandemic. They might have been paycheck to paycheck, but they were going along surviving,” she said. “The unexpected death of somebody just destabilized them.”

Through the program, each household received $2,000 in cash assistance and were connected with social programs such as disability benefits or food stamps. A measure under consideration by the California legislature would create trust funds for COVID orphans, with as much as $8,000 available to eligible youth when they turn 18.

And though not COVID related, experts point to an effort in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania as a stand-out example of local government systematically identifying youth who lost caregivers. A hotbed of the opioid epidemic with an overdose rate triple the national average, the county’s Department of Human Services matched death records to birth certificates and identified over 1,000 youth 18 or younger who had lost a parent to an overdose.

“A first step [for localities looking to support grieving youth] could be … understanding where these bereaved children are located,” said Treglia. “Then you can develop a more targeted approach to finding them and you can tailor interventions to their needs.”

‘So much pain’

Even without a systematized method for identifying COVID-bereaved youth, New York City schools have implemented other measures to help students in mourning. In spring 2021, the city announced it would hire 500 additional school social workers.

“There was a clear understanding that they would need more of us,” said April Gurley, a 10-year veteran who this year stepped into the role of supervisor of North Queens school social workers. “We were [responding to] this massive amount of trauma and grief that was happening in our city.”

The Department of Education has also invested in professional development for teachers, with over 3,800 NYC educators trained in grief sensitivity by David Schonfeld, founder of the National Center for School Crisis and Bereavement.

One positive result that has come of the pandemic, said the expert, is that far more educators have become attuned to the needs of grieving students. In a 2020 survey conducted by the New York Life Foundation and the American Federation of Teachers, three-quarters of educators reported that COVID has opened their eyes to the immense impact of grief and loss.

Teachers serving children who have experienced the death of a loved one should acknowledge the loss rather than ignore it, Schonfeld advises.

“There’s a tendency to avoid talking with children who have been through a crisis or dealing with a death because you don’t want to upset them,” he said. “Saying nothing is exactly the wrong thing to say because it communicates either that you’re unaware or you’re unwilling to provide support.”

But professional development is only a first step, said Morris, of Harvest Collegiate.

“Being trained in this and actually doing it with a real teen are two very, very different things,” the counselor said.

Last year, in a college advising session, a student disclosed to Morris that they had lost a grandparent. The student was not close with their parents and “their sense of themselves as a person came from that grandparent,” Morris recalled.

“I was shocked,” she said. “They were experiencing so much pain.”

On the fly, she had to figure out how to support the teen, who she said had largely checked out of their academics. She referred them to the social work team, but touched base periodically over email and text. “Hey, how are you doing?” she would ask. “What can I do to help?”

Unfortunately, many NYC students dealing with grief aren’t lucky enough to receive support from a counselor like Morris. When Melissa Keaton, the Flatbush mother whose father passed away, sought out mental health support for her daughter, the therapists she contacted were at capacity, she said, and the school mental health services did not reach out to the family.

Meanwhile, a book the class read called The Tiger Rising features a young protagonist whose parent has just died. The reading triggered painful memories for Melanie.

“I did email the teacher to let her know that it’s a sensitive topic,” recalled Keaton. “And she just said, ‘OK, well, I’ll keep that in mind,’” but provided no accommodations.

Such instances, said the DOE, are outliers.

“Every one of our schools is a caring and supportive environment where our students can connect with one another, communicate with a caring adult, and access the resources they need to heal as we emerge from the pandemic,” said spokesperson Suzan Sumer.

But despite educators’ best efforts, pandemic circumstances continually put teachers in emotionally charged situations that they don’t always know how to best navigate, said Shapiro-Nussen.

Recently, a first-grader who had lost a parent in September was exiting the classroom when she turned and asked whether the Bronx special education teacher planned to see her mother after school. Shapiro-Nussen was unsure of what to say; she herself had lost her mom to COVID.

“No, sweetie, I’m not gonna see my mom for a really, really long time,” the educator responded. “My mom is on a really, really long vacation.”

“Was it the right choice?” wondered Shapiro-Nussen. She asked the school counselor. Next time, be honest, the counselor advised.

Angela Torres, for her part, turned to those around her for support processing the loss of her mother. She created a COVID bereavement group that met regularly over Zoom in 2020 and grew to about 20 members through word of mouth, Facebook posts and circulating information at her church. Those conversations allowed her to finally begin to heal, she said.

Schools can take a page out of that book, she said, and facilitate conversations between peers and caring adults to help grieving students like her daughter recover.

“Community,” said Torres. “That’s our ticket out of this.”

Illustration by Marianna McMurdock for The 74.

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!