The 74 Interview: New L.A. Schools Chief Alberto Carvalho on Declining Enrollment, Academic Recovery and How ‘Failure is Not in My DNA’

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

See previous 74 Interviews: United Federation of Teachers President Michael Mulgrew on two years of pandemic education, author Amanda Ripley on trust in American education and Superintendent Michael Thomas on being a Black leader in a white school system. The full archive is here.

Alberto Carvalho, who took over as superintendent of the Los Angeles Unified School District just two weeks ago, wasted little time in setting ambitious goals for his new administration. In a 100-day plan unveiled last week, he said he would focus on academic recovery and consider shifting funds from the district’s expensive COVID testing program to pay for it.

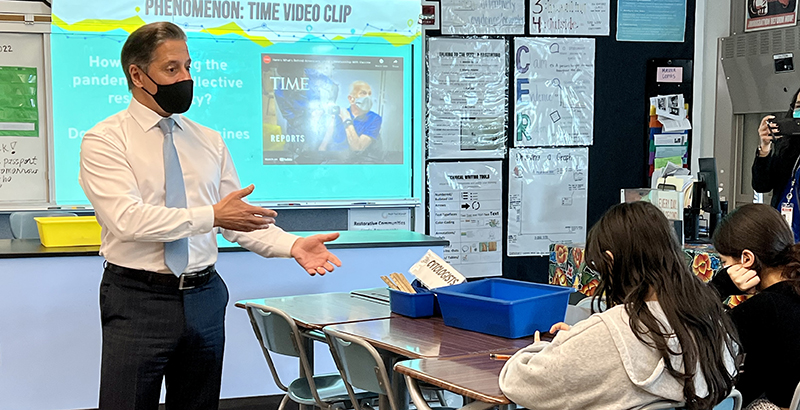

He also wants to reduce class sizes, expand early learning and streamline hiring to address staff shortages. The agenda, which he discussed during a virtual welcome reception Thursday, came after an already jam-packed two weeks in which he attended his first school board meeting, met with each one of the district’s union presidents and taught two biology classes.

The nation is watching whether the success Carvalho had as the 14-year superintendent of the Miami-Dade County Public Schools will follow him to the nation’s second-largest school district. In December, the school board voted unanimously to hire the award-winning leader, with board Vice President Nick Melvoin calling him “the right person to lead L.A. Unified students out of this pandemic into a better future.”

On Friday, he spoke to The 74 about his plan to live up to those high expectations. “I’m very optimistic about the possibility in Los Angeles,” he told The 74’s Linda Jacobson. “If I wasn’t, I wouldn’t be here. I chose L.A. as much as L.A. chose me. I have never failed. I’ve made mistakes. I’ve erred. I’ve tripped. I’ve fallen, but failure is not in my DNA.”

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The 74: Talk a little bit about declining enrollment, which fell by 27,000 students in Los Angeles this year. What’s on your agenda for getting families to come back and attracting new families?

Alberto Carvalho: That’s not unique to L.A., nor New York or Chicago — or most urban centers across America. Affordability has been significantly diminished and wages have not kept pace. That has forced families to move, and when the family moves, they don’t leave the kid behind. There has been significant internal mobility that has shifted membership in and out at the school system.

Then there is this third arena that really concerns me — families and students that have completely disappeared. Calls have been met with disconnected phone lines and knocks at the door. The neighbor does not know. We are beginning to learn anecdotally that some of these families may have had a fragile immigration status. They made decisions as a result of prior immigration protocols and obviously have not returned. It’s a complex issue. Other parents have pulled students from the public school system and moved to their second home because they could afford a second home and pay for private tuition.

Now the solution: In L.A., if you want choice, you have magnets and you have charters. Then there are district-affiliated charters and independent schools. Whoever decided to restrict choice on the basis of those parameters? There are single-gender schools, career academies. Choice does not need to conform to magnet or charter. Where are the programs in L.A. where we see long waiting lists of parents? Why aren’t we expanding more of those programs to where the demand is?

You’re talking about more of those programs in neighborhood schools?

Correct. Have we done an analysis about the amount of time a child is on the bus to get to that one program that really motivates him or her — that great engineering program, fine arts, performing arts, cybersecurity, robotics, STEAM, STEM, dual language, dual enrollment, International Baccalaureate, Cambridge, whatever?

I can fill an entire wall with a repertoire of options for parents. Why aren’t we offering all of that? L.A. Unified is a much bigger district than Miami. L.A. Unified has about 300 magnet programs. Miami-Dade offers 1,100 choice options. We have work to do. If we don’t do that, we will continue to bleed out students because parents are living in a reality where they have an entitlement to choice. If we don’t do that, it is tantamount to burying our head in the sand as a tsunami of choice washes over us. I choose to ride the top of it. I think it’s better for kids, it’s better for communities, and that is one of the key elements of reenergizing interest in our public school system.

On Friday, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention updated its guidance on masking, saying schools can drop mandates when COVID-19 risk is medium or low. Any reaction?

We learned that the state of California and the CDC are relaxing protocols with one significant exception — L.A. County. But conditions have improved significantly in our community as a function of good weather, but also because of the insistence on vaccination, on masking, on testing. We are waiting now on additional data from the county but also guidance from Sacramento specific to school protocols. One of the elements that we are carefully analyzing right now is the possibility of relaxing testing protocols particularly at the secondary level. It’s a very costly proposition. The frequency and cadence is churning through financial resources.

Do we need to continue to invest at this level? We have an opportunity to reinvest those dollars in educational programs, in tutorial, acceleration and social-emotional programs.

Is that something you think the union would oppose?

We will need to have an open dialogue with the bargaining units. I will not surprise our collective bargaining representatives. But if we are a science-driven district, we follow the science not only when things are getting bad; we also need to follow the science as conditions improve.

Many parents say that they want more tutoring, especially small-group and one-on-one tutoring. Why was that not spelled out in your 100-day plan?

It was. When I speak about an augmentation of educational opportunities, before and afterschool programming, that is inclusive of tutorial services. When I speak about the concept of year-round schooling opportunities, I’m not singularly speaking about schools being open. I’m speaking about before- and afterschool tutorial services that can be provided by the school system, but also by private entities, not-for-profit entities. When I talk about maximizing these educational opportunities, that’s exactly what I’m describing. It was not ignored. It is actually very much part of the strategy moving forward.

I think when parents hear terms like expanded learning opportunities and afterschool, they just think of large groups. They don’t think that means the high-dosage models that have received a lot of attention.

It’s both and.

I was struck by how David Turner [manager of Brothers, Sons, Selves] challenged you on the issue of school police. He said he was disappointed to see the increase in resource officers under your tenure in Miami. What is your position on that, considering the Los Angeles district took a strong stance last year on redirecting funding from school police officers to improving school climate and the achievement of Black students?

I have inherited a policy position that has reduced the budget and implemented a different methodology of protective actions around schools. Rather than the presence of a school resource officer on campus, it’s more of a mobile unit that provides someone support for safe passage to and from school and is able to rapidly respond to emergencies. That is a decision made by the board, supported by a significant sector of this community.

Now that we’ve moved in that direction, have we stood up the appropriate personnel, with the appropriate training in schools from a prevention perspective? Have we identified restorative justice practices, been effective at avoiding, preventing and or resolving and managing a crisis that would have otherwise been addressed by a police officer? We’re not there yet.

My concern is that [police] have been removed, and the element that will in a more systemic and more preventive way benefit our kids has not fully been fleshed out. That, too, is part of the 100-day plan.

Alicia Montgomery, executive director of the Center for Powerful Public Schools, watched your presentation and reviewed the plan. She mentioned to me that the school system’s six local districts and all the smaller communities of schools each have their own goals and objectives. She said she has been struck in the past by the “sheer resistance to consistency across the district.” You talked a lot about alignment in your plan. Where would you like to see a more universal approach and where should there be room for autonomy?

I’m a huge believer in the concept of earned autonomy, implementing a model that strikes the appropriate balance, that sweet spot. The board’s equity-driven agenda should be ubiquitous. That requires clear communication, continuous monitoring of student performance, attendance data, critical incidents of absenteeism and a universal guarantee of the appropriate resources. That cannot be left singularly in the hands of local leaders. That said, there is room on the other side of the balance for leadership that works best closer to the school. I do have some concerns where it’s working well versus where it’s not working well.

Can you give an example?

I would rather not. There are many different areas in Los Angeles where local leadership has navigated this balance fairly well. In other areas, it is not as clear to me that the coherence is where it needs to be.

Your plan mentions creating a collective bargaining strategy, and I know some would like to see a lot more transparency in negotiations with the union. Should that be a more open process?

I’m a huge believer in transparency, so let’s begin there. There is no way that we’re going to maximize opportunities for students through the existing collaboration with labor partners. [We need to be] developing and executing a sound, reasonable strategy that’s based on compensation philosophies that support recruitment and retention of a highly qualified workforce. That’s huge for me. It’s needed for the school system right now. We’re having a difficult time recruiting teachers. Fifty percent of teachers across the country are leaving the profession before retirement. That is shocking and that’s the first time that has happened in the history of our country.

The typical negotiation process begins with management declaring that there is no money and labor providing a list of demands. Sometimes lost in that chasm is the answer to the simple question: What do the kids need and can we rally around a common set of goals?

I’ve been here about a week now and I’ve had conversations with every single labor president, and I did that in advance of the 100-day plan because I don’t believe in surprises. This work is too complex, too difficult and too important, particularly as we continue to navigate the tail end of this pandemic. That’s going to be my approach to the labor negotiation process that we are rapidly going into.

The U.S. Department of Education recently reminded districts that they are responsible for providing students with disabilities the services they did not receive during remote learning. Are you evaluating what the district is required to do and have a plan for providing those services?

During the pandemic, students with disabilities were among the most impacted, the most fragile communities of students, and have lost the most ground. We need to start from that perspective. By what means shall we accelerate and where have we fallen short in terms of providing the best educational environments? Where do we need to increase inclusion rates across the district? Where must we contemplate additional improvements for parents of students with disabilities who have maintained them in a virtual environment? Are there opportunities for us to speak with the parents and demonstrate that perhaps the option they selected is not adequately addressing the needs of their children?

This is an ongoing process with the federal government. I am aware of the issue and I’m currently engaged in discussions with federal entities regarding this topic. At the end of the day, this is a fragile community of students and I think we recognize two years into this pandemic some of the detrimental impacts that these students have suffered.

How often will you teach? Do you want to run your own school like you did in Miami?

I have now taught two high school biology classes since I’ve arrived. That’s as much fun as anybody in my position can ask for. I need to remain connected to what happens in schools, at a leadership level, in a supportive role. But if I am to remain real, I need to have access to students through meaningful instructional opportunities. That’s what sustains me. This can be a difficult role, and I don’t know how to do it from the comfort of the ivory tower, or the safety of backstage. I need to be on the edge of that stage, feeling the warmth and the social interaction from students and schools. I’m going to be very active and engaged with school principals, with teachers and in the classroom. It’s actually a topic of negotiation and conversation with my own team, how we make that feasible on a very regular basis.

Finally, when the news hit that you were coming to Los Angeles, I spoke to a long-time parent advocate who said even the most talented leaders have been driven away from this job. I know you said you’re here for the long haul, but what is your reaction to that statement?

Why would anybody want to do this? Because we cannot abandon two elements of America — the importance of public education and the viability of cities and urban education, where the needs are heightened. Are there easier ways of impacting children? You can go be a superintendent of a very affluent, small district where you don’t have that diversity, you don’t have kids who are children of immigrants.

I think we need to paint a picture of hope. I’m very optimistic about the possibility in Los Angeles. If I wasn’t, I wouldn’t be here. I chose L.A. as much as L.A. chose me. I have never failed. I’ve made mistakes. I’ve erred. I’ve tripped. I’ve fallen, but failure is not in my DNA. When we decide to accept failure for ourselves, we are condemning kids to the same fate, and that’s not me.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)