Superintendent of San Antonio’s Largest, Most Diverse District Weighs Reopening Schools First for Students Who Need Them Most

Like many educators dealing with the fallout of COVID-19, Northside Independent School District Superintendent Brian Woods is losing sleep, brewing over plans to reopen schools first to the kids who have lost the most.

No two days have been the same since schools closed in March. No two days will be the same for a long time, he suspects. Every plan has a contingency plan, and every contingency plan has multiple variations to account for community outbreaks, funding losses and the numerous “what-ifs” of bringing 107,000 students back to school at some point.

The “what-ifs” are about to become realities.

Texas Gov. Greg Abbott announced Monday that schools could reopen on June 1 for limited in-person instruction. That announcement, and the likelihood of delayed or staggered school openings in the fall, has district leaders around the state, including Woods, floating the possibility of an equity-driven maneuver: opening school buildings first to the students who need them most — those who rely on the school building for safety, food security and intensive academic interventions.

“If we can bring kids into buildings in a safe way,” said Woods, who leads San Antonio’s largest, most diverse school district, “we’ve got to identify those kids who are in greatest need academically, as well as as socially and emotionally, and prioritize them.”

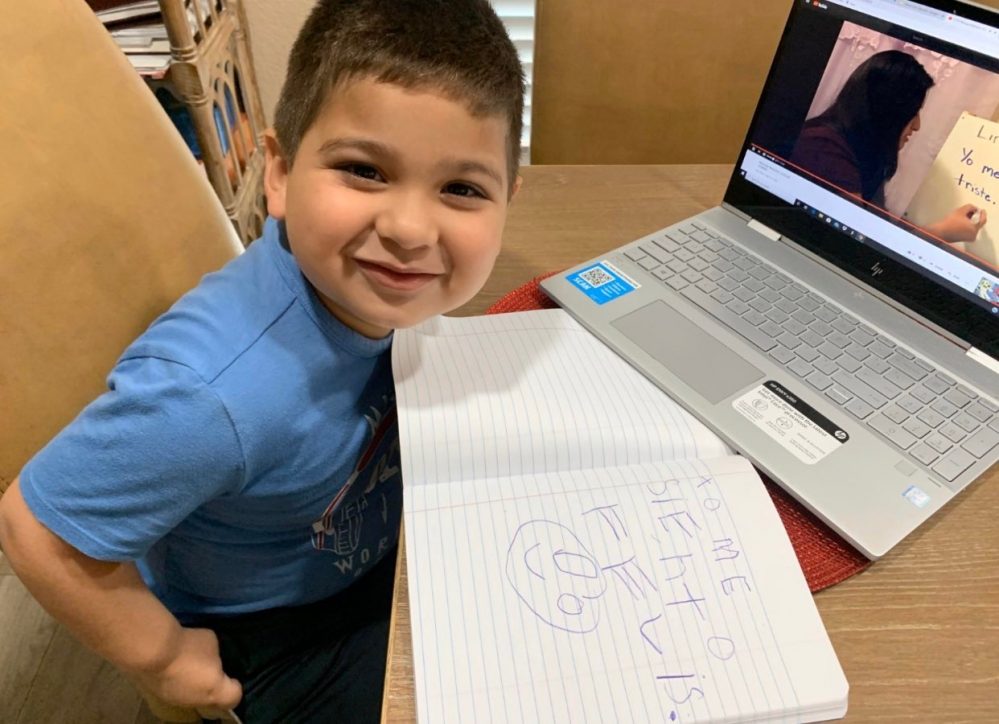

Northside ISD is a microcosm of the massive resource gaps between communities around the country. The district’s 120 schools range from less than 8 percent of students on free or reduced-price lunch to over 95 percent. The pandemic has laid bare the myriad consequences of such divides, with some homes stocked with the food, internet and space to make learning from home a manageable pivot, and other homes far more destabilized by the sudden school closings.

“It’s keeping me up at night, that’s for sure,” Woods said. “So some of my summer and fall planning is driven by that massive equity concern.”

Re-opening with equity

It seems likely, Woods said, that reopening will not be a once-and-for-all return to normal. Tough choices may have to be made on a regular basis, beginning this summer. In addition to Abbott’s summer announcement, the Texas Education Agency has already offered flexible guidance to districts that might want to take advantage of year-round school calendars or six-week intersession breaks to focus on academic interventions. The state has also provided voluntary tests for parents and teachers to assess learning loss and guide their decisions.

Without careful consideration, staggered reopenings and blended learning plans could exacerbate the already uneven learning losses. Woods and others are hoping that careful planning could also ameliorate them.

Woods is fully aware of the academic consequences of economic divides. In Texas state ratings, most of the district’s A-rated campuses enroll more affluent students than its C-rated campuses.

Only six of the 120 schools in the district received “D” ratings in 2019, and none failed; Woods attributes that to educators’ ability to control what goes on within the school building. With kids confined to homes with even more unequal resources — parental time, internet speed, private tutoring access, even quiet workspaces — Woods said, every day is pulling them further apart academically, socially and emotionally.

“In the school building you can reduce variability in the experience from kid to kid by putting them with great teachers,” Woods said. “Now that [struggling] student is faced with circumstances that we used to be able to control for at least for a few hours a day.”

One boon of economic diversity — which the majority of San Antonio’s 17 districts do not have — however, is the ability to shift resources according to needs. Many of the families in Northside, and many of the schools, have the resources to get by, to thrive even, with online learning during the pandemic.

Others, Woods knows, “are really struggling … they’re used to structure, and having a really safe place … when that’s gone, for some kids that’s a massive loss.”

It’s a dilemma that calls to mind the oft-cited difference between equality and equity. With equality, everyone gets to come back to school together. Teachers would take on the six months of unequal learning loss in the classroom, trying to get everyone caught up within next year’s 180 days of instruction.

Equity, on the other hand, puts more intensive resources where they are most needed. Those resources may be school days. They may be the limited seats in socially distanced classrooms. Equity might look different in every school, every district, every city.

Opening will be messier than closing

During closures, area districts were able to move in lockstep when announcing timing and duration, meeting twice weekly to coordinate messaging. This helped eliminate confusion and competition for resources among the 17 districts within the city limits, as well as several in surrounding counties.

“That was a good decision,” Woods said. “It set the tone for us to try to stay on the same page.”

Closing, however, was in some ways a more straightforward decision, Woods explained. The public-health risk affected every district, and there were too many unknowns to consider alternatives. No district was fully prepared to move to online learning, though some had fewer issues with internet connectivity. Broadband access in the western, southern and eastern quadrants of the city is significantly lower than in the north.

Coming back in the fall, he explained, each district will have to consider its unique circumstances. Most had different start dates to begin with, and superintendents have publicly stated that they intend to adhere to those dates — whatever that may look like.

“Just getting into the school building,” Woods said, is going to vary from campus to campus. In some neighborhoods, he explained, everyone walks to school. Others are more dependent on buses, which pose a greater challenge for social distancing. Some schools were designed with a single entrance, for safety. Now having hundreds of kids squeezing through a set of double doors is a health hazard. Every district will have to solve for those variables between its own schools.

For campuses that are operating at or above capacity, Woods said, it may not be possible for every student to attend eight hours of school every day. In districts where enrollment has been shrinking in recent years, as it has in many of the smaller San Antonio districts, they may be able to spread out more.

“We’re going to be balancing the potential for massive learning loss that may or may not be able to be recouped,” said Woods. “We’re going to be balancing social-emotional wellness, and kids who really need to be in a school to eat. All this stuff is going to be balanced against public health.”

Digital realities

Digital assets will be another deciding factor in what districts will be able to accomplish in the fall, how much they can depend on remote learning for social distancing, response to COVID-19 flare-ups, credit recovery and other academic interventions.

The massive, sudden shift to online learning informed the way Northside thinks about one-to-one technology and connectivity, Woods explained. Students’ personal smartphones, which some districts include in their one-to-one plans, are not sufficient for meaningful schoolwork, he said, “even if they’ve got a world-class phone.”

While phones have the computing power and apps necessary for basic research and communication, they are not sufficient for writing or creating digital presentations. Districts need to prepare to provide laptops and Chromebooks to the majority of students. The notion of the “family computer,” he explained, doesn’t work during school closures.

“Even in our very solidly middle-class families,” Woods said, “we saw a significant interest in [district-issued] devices.”

Of course, connectivity issues are often more fundamental. Access to the internet is not a given in most school districts in San Antonio, including Northside.

The community data tracking nonprofit SA2020 breaks down internet access by city council district. In the four city council districts served by Northside, household internet access ranges from 75 percent to 87 percent. Parts of Edgewood Independent School District and San Antonio Independent School District serve areas where only 54 percent of houses have internet access, in part due to the lack of last-mile broadband infrastructure.

Woods would like to see a New Deal-style public works program to expand broadband infrastructure with the goal of creating a new public utility. If school closures and distance learning are going to be part of the “new normal,” he said, then eliminating these kinds of disparities between homes has to be a public priority — for everyone.

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

;)