Study: In 28 Districts, Middle and High School Students Lose More Than a Year of Learning Due to Suspensions

In 28 districts across the U.S., students in middle and high school lost more than a year of learning due to suspensions, according to a new study released Monday.

The study from the Civil Rights Project at UCLA analyzed discipline data from 2015-16 for almost every district in the nation. The most extreme losses ranged from 183 days in Edgecombe County Public Schools in North Carolina to 416 days in Grand Rapids Public Schools in Michigan.

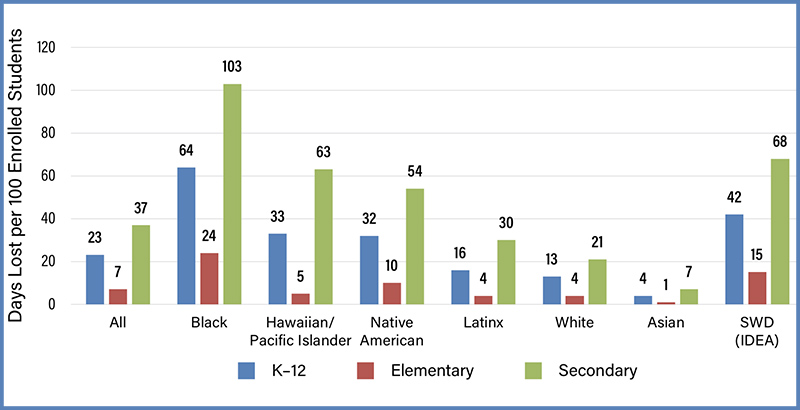

The study also shows that while the racial gap among secondary school students at risk for suspension has narrowed since 2009-10, Black students still miss almost two-thirds of a school year of instruction for discipline reasons — 103 days per 100 students, compared to 21 days for white students.

Secondary students with disabilities also miss significantly more days because of suspensions than students at the elementary level — 68 compared to 15.

The breakdown by level is important because middle and high schools “provide very different environments than found in elementary schools, and … tend to use suspensions from school far more frequently,” said Daniel Losen, the director of the Center for Civil Rights Remedies at UCLA.

Middle and high school students lose five times the number of instructional days due to out-of-school suspension compared to those in the elementary grades — 37 days per 100 students compared to seven for elementary school students.

Based on the U.S. Department of Education’s 2015-16 Civil Rights Data Collection, “Lost Opportunities” builds on the researchers’ earlier work, in partnership with the ACLU, showing that suspensions added up to more than 11 million days of lost learning. It comes as some districts across the country have ended contracts with police departments and school resource officers amid nationwide outrage over racial disparities in law enforcement’s treatment of Black men and boys. The report recommends discipline policies that help students improve their behavior — such as restorative practices and those that address students’ social and emotional well-being.

With students already losing instructional time because of school closures, Losen and co-author Paul Martinez wrote that it’s especially important now to look for ways to avoid removing students from learning opportunities.

“When students return to school, the pre-existing gaps in the opportunity to learn will have been seriously increased by the pandemic,” they wrote. “The need for alternatives to suspending students has never been more obvious.”

Mylien Duong, a senior research scientist at the Committee for Children, which provides social-emotional learning programs, agreed. “Suspending students returning to school after several months will not only push them further behind, but it may heighten stress and lead to negative attitudes about school,” she said.

Calls to reinstate discipline guidance

Because the department has delayed release of the 2017-18 data, it’s hard to know whether recent district efforts to implement less punitive measures, along with state legislation limiting suspensions, have reduced disparities. More recent data would also show the impact of the Obama administration’s 2014 discipline guidance, which was intended to reduce racial disparities in suspensions and expulsions.

U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos rescinded that guidance in 2018, saying it was a matter for states and districts to handle on their own. But the Civil Rights Project is now among those — including House Committee on Education and Labor Chairman Bobby Scott, D-Va. — calling for the secretary to reinstate the guidelines.

While some conservative groups supported DeVos’s withdrawal of the guidance, Michael Petrilli, president of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, said, “There’s a reasonable compromise to be had, which is to reinstate the guidance with a few key edits.” Before DeVos withdrew the guidance, Petrilli suggested revising the policy by deleting what he called a “de facto racial quota system.”

The Civil Right Project has also filed a freedom of information request for the updated information, but so far, the department has not complied, Losen said. He added that he’s particularly interested in school policing data, which states and districts are supposed to include on state report cards to comply with the Every Student Succeeds Act. He said no state has complied and several large school districts, including New York City and Los Angeles, aren’t reporting school-related arrests of students.

“It’s hard to fathom that we can’t know how many students were arrested in a school district,” he said, “yet we every year we can see the proficiency scores for every racial [and ] ethnic group in reading, math and … other subjects.”

‘Tools to be supportive’

The 2015-16 data collection was the first school year in which districts had to report the number of days a student was suspended, not just the number of suspensions. That matters, Losen said, because two groups of students might have the same suspension rate, but the rate alone doesn’t capture whether a student received repeated suspensions or whether a given suspension was for one day or a full week.

Calculating days suspended provides a fuller picture of “the extent to which harsh suspension policies are contributing to unequal educational opportunity and thereby to counterproductive school environments,” he said.

Losen added that examining disparities at the district level is important because “districts exercise control over principals and over resources needed to implement effective discipline reforms.”

Josh Civin, chief legal officer for the Baltimore City Public Schools, said focusing on equity and stressing a “restorative approach” is a key part of the district’s reopening plan, recognizing that many students have already struggled with staying engaged in learning during school closures. Using suspensions as a last resort is also written into Maryland state law.

He said both Baltimore schools and the Montgomery County Public Schools, where he worked last school year, made reducing racial gaps in suspensions a goal before the Obama-era guidance and that removing it hasn’t changed those efforts. District leaders, he said, try to give teachers and principals “the tools to be supportive” and encourage positive behavior in students. He added that because the school police officers work for the district, it’s easier to have the same expectations of those employees.

Nonprofit organizations have also played a major role in pushing districts to find alternatives to suspending students and involving law enforcement in behavior issues. The Gwinnett Parent Coalition to Dismantle the School to Prison Pipeline in Georgia, for example, has pushed to ensure that the Gwinnett County Public Schools student handbook includes violations that could lead to a referral to a school resource officer and that state report cards publish student discipline data as a measure of school climate, said Maryln Tillman, executive director of the organization.

“We try to work collaboratively with the district but that is not always possible,” she said, adding that with schools closed, she has seen students reassigned from their virtual home school to a virtual alternative program, even if it lacks the same classes “You’re specifically telling that child they should lose all future opportunity based on their last mistake.”

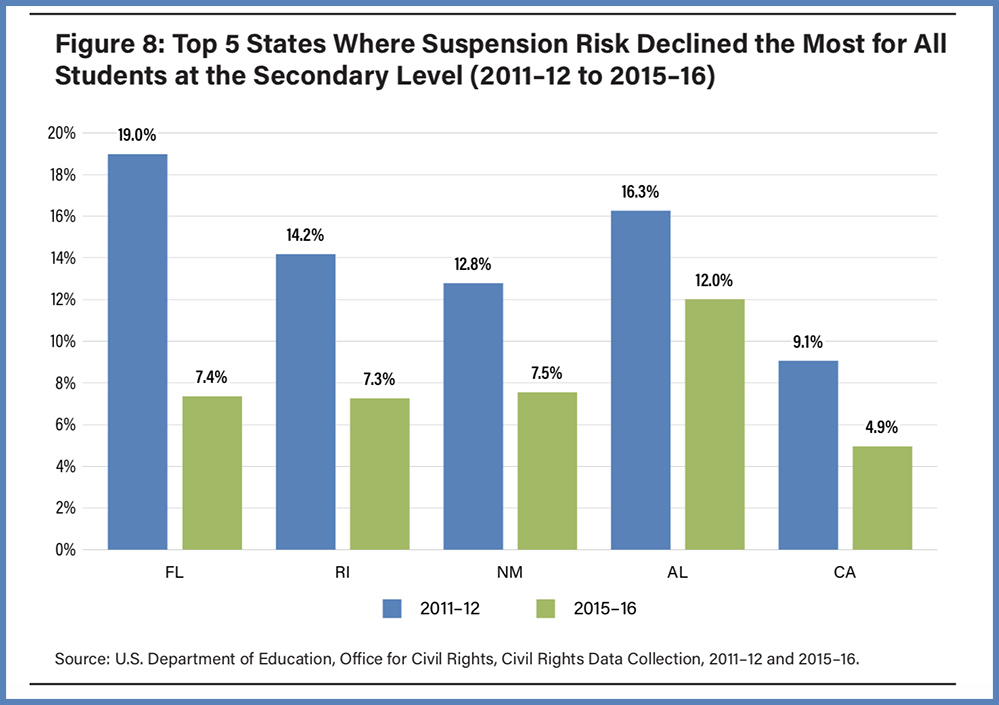

Improvement since 2011-12

The report also provides data showing that suspension rates, by racial subgroup, have declined since 2011-12. And while no states show overall increases in suspensions, a few — Nevada, Arkansas, and North Dakota, for example — have seen rates for Black students increase.

At the district level, Miami-Dade County Public Schools had the largest drop in suspensions between 2011-12 and 2015-16 at the secondary level, 15.9 percentage points, while the Richmond County School District in Georgia, which includes Augusta, saw the largest increase, 17.1 percentage points.

While DeVos has recommended eliminating some data from the Civil Rights Data Collection, the report recommends adding new categories, such as the primary reason for a suspension, and calls on the Government Accountability Office to investigate why states and districts are not reporting some of the arrest and discipline data required by the Every Student Succeeds Act.

Karen Webber, the director of education and youth development at the Open Society Institute, a Baltimore-based foundation, said the report adds to other research on the positive results of restorative practices. “Dan Losen has once again signaled to public school districts across the nation that misguided and overly punitive exclusionary discipline practices are failing our secondary students, with an especially disastrous impact on Black and brown students,” she said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)