Schools in Portland, Maine, Open Their Arms to Refugees, but Academic Progress Remains Elusive. Now, an Immigrant Superintendent Is Pushing for Change

When Tae Chong remembers what Portland, Maine, was like 40 years ago, he doesn’t mince words.

“If someone didn’t call me a racial epithet,” said Chong, who emigrated from South Korea in 1976, “I was like, ‘What happened? Was there some kind of diversity training today?’”

Back then, says Chong, the school district was overwhelmingly white; he jokes that his family and their Vietnamese neighbor made up the district’s entire Asian-American population. But in 1980, Congress passed the Refugee Act, increasing the number of refugees the United States accepted each year and turning Portland into a resettlement site for those fleeing violence and oppression. Since then, the percentage of residents born outside of the United States has more than tripled, according to census data. Today, Portland’s 6,800 students speak 67 different languages, and almost half are non-white. The percentage of students learning English is nearly twice that of New York City students.

The effects on the district and the city — not to mention the state, one of the nation’s whitest — have been both subtle and profound. Roughly 5 percent of students are homeless — nearly five times the statewide average. The district employs 12 full- or part-time interpreters, and a slew of nonprofit organizations like Welcoming the Stranger and the Immigrant Legal Advocacy Project offer support to immigrant communities. The ethnic potpourri has also turned Portland into an international foodie hot spot. Bon Appetit magazine named the city of 67,000 the 2018 Restaurant City of the Year, and the accompanying article highlighted a Vietnamese street food vendor and four Japanese offerings, including one that serves a Turkish crab dip.

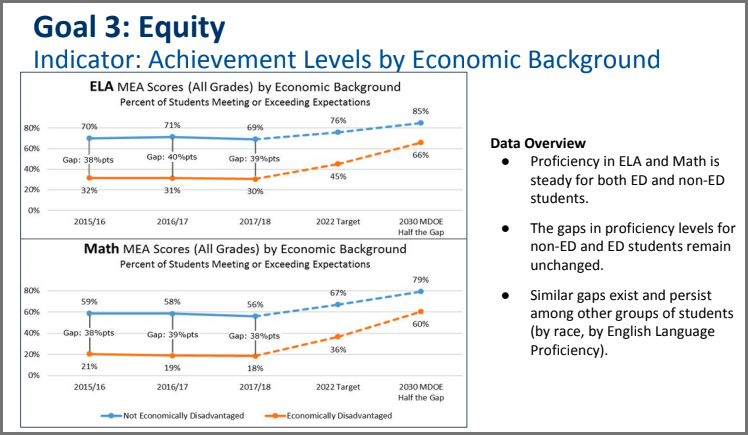

But for minority students — whether they immigrated to the city recently or, like Chong’s two children, are second-generation Portland public school students — many aspects of school life have been stubbornly resistant to change. In every racial or ethnic group besides white, Portland students scored worse than their statewide peers on the 2017-18 math and science tests in grades 3-8. Just 11 percent of black high school students in Portland met or exceeded expectations on that year’s state math test. And, according to data presented at an August school board meeting, a multiyear effort to boost the performance of economically disadvantaged students and students of color has yet to yield significant progress.

Roberto Rodriguez, the chair of Portland’s board, called the continued achievement gaps “incredibly frustrating.”

The diversification of Portland’s schools is an extreme version of demographic trends around the country. Between 2000 and 2015, the percentage of white students enrolled in public schools decreased in every region nationwide, and today the majority of students in America’s public schools are non-white. But Portland’s huge influx of immigrants, many of them victims of significant trauma who arrive with very limited resources, has made the district’s experience especially pronounced.

Portland’s students include four children from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, who left with their father after he was stabbed by a soldier; four children from Angola who traversed eight countries by plane, bus, boat and horseback before coming to the U.S.; and three children, also from the Congo, who arrived after a six-month journey that included a four-day stretch without food.

“If you just look at where the conflicts in the world are and where civil wars are happening, pretty soon you’re going to see those people in Portland,” said Grace Valenzuela, who immigrated to Portland in 1986 from the Philippines, where she worked as an English teacher in a refugee camp. She currently oversees the district’s Multilingual & Multicultural Center.

Living ‘that immigrant reality’

Officials there maintain that they don’t have to make a false choice between students’ social-emotional needs and academics — the educational equivalent of walking and chewing gum at the same time. But after several years of targeted reforms, the district has more to show for its advocacy of immigrant students’ rights than for their academic progress.

If there’s a superintendent whose biography is supremely well-suited to tackling this conundrum, it’s Xavier Botana, whose family left Cuba in the aftermath of the Castro-led revolution when he was a year old, and eventually settled in the United States. Botana grew up learning English in schools in Illinois and Pennsylvania. He started his career as a bilingual and English-as-a-second-language teacher in the Chicago suburbs and went on to serve as an administrator in Chicago, Oregon and Indiana.

“I’ve always lived with the reality of not quite being from here and not quite being from somewhere else either, and having to live that immigrant reality, which I know many of our kids live with as well,” said Botana, 57.

Botana became Portland’s superintendent — the district’s sixth in nine years — in July 2016, months before President Donald Trump’s election. His appointment came during the last term of former Maine governor Paul LePage, who boasted that when it came to divisive rhetoric and governing style, he “was Donald Trump before Donald Trump became popular.” LePage claimed that asylum seekers were “the biggest problem in our state” and referred to “people of color or people of Hispanic origin” as “the enemy.”

On the same day in early 2017 that Trump signed an executive order barring immigrants from multiple Muslim-majority countries from entering the United States, a Portland resident hurled racial slurs at high school students from Mexico, Sudan and the Democratic Republic of the Congo; he later threatened them with a screwdriver. Botana defended the students at a rally, and in an open letter he decried the “noxious environment” Trump had created for immigrants and people of color. He later worked with the school board to pass resolutions opposing xenophobia and Islamophobia.

Botana has also taken on national battles in support of Portland students.

One of those students was Allan Monga, who fled his native Zambia by himself and arrived in Portland in 2017, when he was 18. While he won’t disclose what led him to leave Zambia, citing his open asylum application, he acknowledged that he lived for a time in a teen shelter, where a caseworker helped him enroll in high school.

He found an apartment after six months. Once the social worker at Monga’s high school heard the news, she sent an email to colleagues providing a list of items that he still needed.

“My house was fully packed, fully furnished within a week,” Monga said.

During that school year, one of Monga’s teachers encouraged him to participate in the National Endowment for the Arts’ Poetry Out Loud competition that invites students to study and recite classic poems. Intensely shy — “When I got on stage, I would literally drop the microphone,” he said — Monga ultimately gave in to his teacher’s persistent urging. He went on to win the school competition, then the regional and state contests.

But as he filled out the paperwork to compete in the national championship in Washington, D.C., Monga realized that asylum seekers were ineligible. He told his teacher, and word got back to Botana. After negotiations failed to break the impasse, Botana directed the district to sue the NEA on Monga’s behalf, and won.

The student ultimately went to D.C., where he delivered renditions of works by W.E.B. DuBois and Lord Byron, but did not emerge victorious. “I appreciated all of the hard work that everyone did,” said Monga, who graduated in June. “They were in the forefront of making sure that I was not shut down.”

Guarding against lowered expectations

Given the Portland community’s embrace of diversity, Botana says activism has been the easier part of his job. The persistent race- and economic-based achievement gaps, on the other hand, stand “in stark opposition to what we want to be as a community,” he said, and he has tried myriad strategies to boost minority students’ performance. Last school year, for instance, the district launched “equity training” for all instructional staff, more than 92 percent of whom are white. The training is designed to promote understanding and appreciation of people from different backgrounds and covers race, power and privilege.

“We have some of the most caring and committed educators that I’ve ever been around, in terms of really wanting to do the right thing by our students, in particular our English language learners, our immigrant kids, our refugee kids,” said Botana. “That’s awesome, and at the same time we have to guard against lowered expectations for those students. Part of our strategies include really giving our teachers the tools that they need to be able to keep an academic focus on students while at the same time addressing the traumatic effects in their [lives] that have brought them to us and challenge them every day.”

Among the core of Botana’s push for equity is proportional representation in Advanced Placement classes, eighth-grade algebra, the gifted and talented program and the special education program. The district aims to have the demographics of students in these areas reflect the district’s broader population.

At Deering High School, for example, which Botana says “serves the most diverse high school student body in New England north of Boston,” minorities made up 48 percent of the student body but only 12 percent of students in AP classes in 2015-16. So Deering tripled the number of AP classes it offered and individually recruited minority students to fill the newly created seats.

Assistant Principal Abdullahi Ahmed, a Somali immigrant, is among the officials who have personally encouraged students to leverage the school’s Challenge by Choice program, which lets a student take any course without completing prerequisite classes. The school’s guidance counselor has expressed concern about high stress levels for students who take multiple advanced classes, but the school partners with nearby Bowdoin College to support struggling students, and Ahmed says the effort is paying off: Minority students now comprise 41 percent of students in AP classes.

The district also changed the admissions criteria for the gifted and talented program, moving from a test that officials said disadvantaged English language learners to educator nominations that encourage the consideration of all students. (Botana is generally skeptical of standardized tests, “even moreso with our diverse students,” he said.) Non-white student participation in the gifted and talented program increased from 13 percent in 2016-17 to 26 percent in 2018-19.

Overall, however, Botana said he was “not that impressed with our progress” in achieving proportional representation. Specific data for class and program enrollment are not yet available, but he said the gaps in representation seem to mirror recently released state test results. In math and English language arts, the percentage of students from low-income backgrounds who met or exceeded expectations in 2017-18 was 38 points lower than the percentage of students from wealthier backgrounds who did so — meaning there had been no shrinkage in gaps that existed in 2015-16.

Based on his initial review of the yet-to-be-released data, Botana noted grimly that similar gaps exist between white and non-white students’ performance and in the enrollment of students in advanced programs and classes.

“Proportional representation [is an area] where we should be able to see changes more rapidly,” he said.

Botana said he has received no pushback to the changes he made to increase equity, but Doris Santoro, a parent of a Portland student who also chairs the education department at Bowdoin, said teachers can grow frustrated as specialized programs become more inclusive.

“For many teachers — this isn’t just Portland, but many teachers who teach in those upper-level tracks — the idea is, ‘Well, if you get into this class, you better be able to do the work,’” she said, “rather than, ‘We need to adjust our pedagogy and the kinds of in-school support we provide the students in order to access the curriculum and perform in the curriculum.’ For teachers who resist altering their pedagogy in the name of excellence, that’s an incredibly problematic stance.”

Chong, who graduated from Portland schools and served on its board from 2002 to 2005, now has two children of his own in the public schools. He thinks teachers should hold the immigrant students to higher standards.

“For crying out loud, [some of the refugees] went from Africa — where there are no people like Mainers, they know nothing about Maine or Maine culture — and they come here in the dead of winter, where it’s minus 20 with four feet of snow, and we’re worried about pushing them? Are you kidding me?” Chong said. “I believe Xavier should be pushing back and telling the teachers, ‘You need to push these kids more.’ Their parents want them to be pushed. Don’t be so nice.”

For now, Botana counsels patience, noting how few cities nationally have made significant progress in eliminating racial achievement gaps. The district is doubling the number of seats in its pre-K program and giving priority to students learning English. It is also investing in intensive coaching for literacy and other subjects as part of an increased budget voters approved earlier this year.

Ultimately, despite the limited progress to date, Botana remains optimistic that the Portland community’s efforts to support its immigrant students will eventually lead to more significant academic improvement.

“I don’t think that this is something that you can just snap your fingers and make it happen,” he said. “I think there’s significant work ahead for us.”

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

;)