Schools Are Now the Leading Target for Cyber Gangs as Ransom Payments Encourage Attacks

New research reveals how meeting hackers’ demands can backfire, feeding a cycle of attacks that are already crippling districts nationwide.

Education is at a Crossroads: Help Us Illuminate the Path Forward. Donate to The 74

Shoddy cybersecurity practices and a willingness to pay ransom demands have made school districts ripe for online exploitation, new data suggest. In fact, they’ve become the single leading target for hackers.

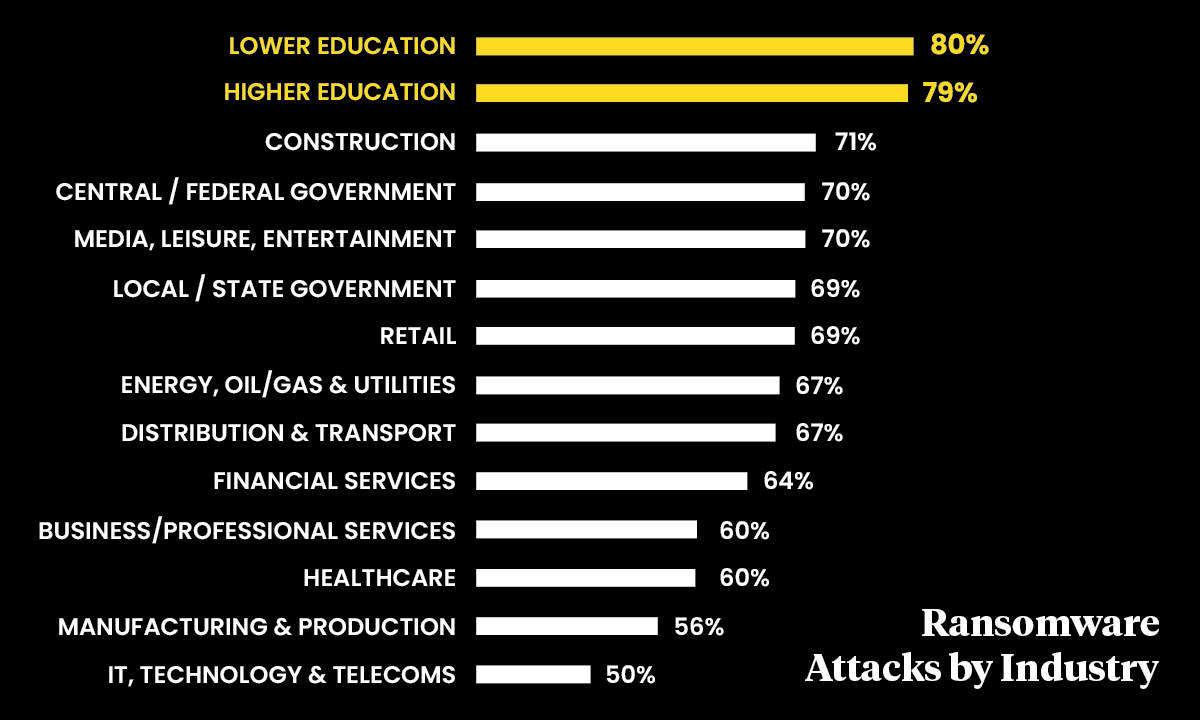

Last year, a startling 80% of schools suffered ransomware attacks, according to a global survey of school IT professionals conducted by the British cybersecurity company Sophos and released last month. That’s a surge from 2021, when 56% claimed they were victims. The rate has doubled over two years, making ransomware “arguably the biggest cyber risk facing education providers today,” researchers found.

The victimization rate against schools was higher than all other surveyed industries, including health care, technology, financial services and manufacturing.

While the Sophos survey included responses from 400 IT professionals working in education globally, U.S. institutions are “the prime target for many of these gangs,” particularly since Russia invaded Ukraine, said Chester Wisniewski, field chief technology officer of applied research at Sophos.

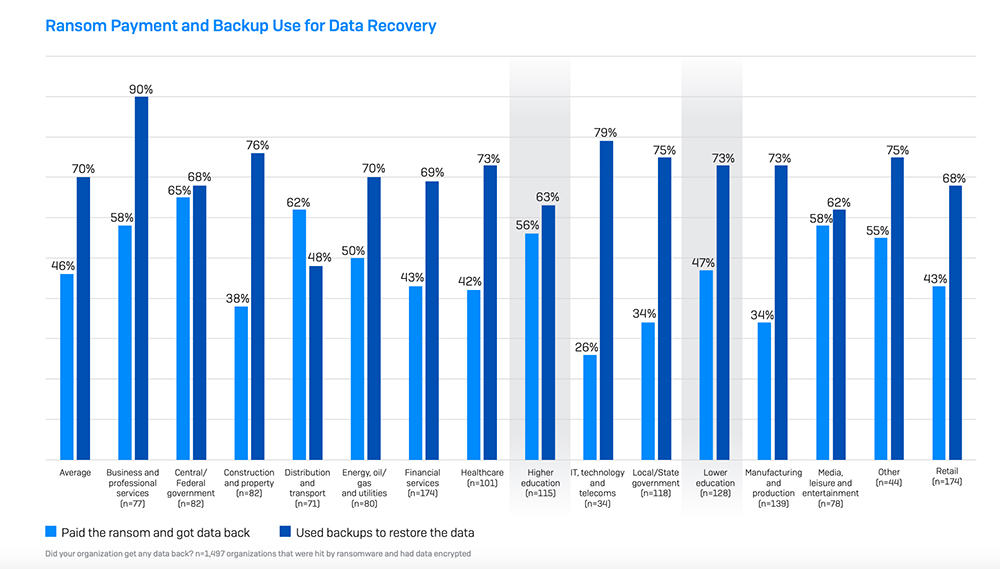

Yet even among American institutions, he said two factors have made schools particularly vulnerable to threat actors. Costly cybersecurity safeguards in schools often fail to rival those in place at major businesses like banks and technology companies. And schools aren’t just easy to hack, they’re also easy to exploit for profit, he said. Nearly half of attacks against schools last year — 47% — led to ransom payments, researchers found, and their willingness to shell out cryptocurrencies to retrieve stolen files may have backfired.

“If a given sector pays more often than another sector, then they get targeted more often and if a given sector is really insecure and it’s super easy to break in, they’ll also get targeted more,” he said. “In the case of education, unfortunately, it’s a double whammy because they do pay very often and they also are really easy to break into.”

The rise in ransomware attacks on schools coincides with the growth in double-extortion schemes, researchers found. In double-extortion ransomware attacks, threat actors gain access to a victim’s computer network, download compromising records and lock the files with an encryption key. Criminals then demand their victim pay a ransom to regain control of their files. If victims don’t pay, the criminals sell the data or publish it to a leak site.

Files contained in those data breaches routinely contain sensitive and confidential information about students, their parents and educators. After an attack last year against the Los Angeles Unified School District, threat actors published highly sensitive psychological evaluations of some 2,000 current and former students. Following a computer breach this spring at Minneapolis Public Schools, a cyber gang uploaded to the internet a trove of stolen files including ones detailing campus rape cases, child abuse inquiries, student mental health crises and suspension reports.

While both incidents were large-scale attacks, many others likely unfold on a much smaller scale, Wisniewski said. Of the 80% of districts reporting attacks, he said the figure likely includes instances of a single student’s or educator’s computer being compromised.

“The sophistication is very low, it’s smash-and-grab stuff,” he said. “They literally are just encrypting a laptop and saying, ‘Pay us $500 for the keys,’ and they don’t have the time nor the skills to bother exfiltrating data and stuff like the big groups do.”

Scott Elder, the superintendent of Albuquerque Public Schools, knows firsthand the challenges that education leaders face when their districts become the targets of cyber criminals. A ransomware attack hit his New Mexico school system last year, forcing the district to cancel classes. Ultimately, the district and law enforcement were able to resolve the attack without paying a ransom. He told The 74 he was surprised that schools have become the top ransomware target because “we don’t have any money.” But he’s well aware that districts are vulnerable.

“The reality is, we have incredibly dedicated people who are working incredibly hard to keep our data safe, but we just can’t pay as much as the private sector,” Elder said. “I’d imagine there are a lot of districts that are struggling to attract top-tier talent to do this type of work.”

Last year, stolen data was encrypted in 81% of cases against schools and attacks were stopped in just 18% of cases before district information was locked, according to the Sophos report. Of schools that had their documents locked behind an encryption key, threat actors made their own copies of the information in 27% of cases.

While schools may be tempted to pay ransoms to retrieve stolen data quickly and minimize harm, the Sophos report offers counterintuitive findings. Recovery costs were higher in districts that shelled out ransoms, even before factoring in the cyber gang’s financial demands. It also took those districts longer to get back up and running, according to the report. While 35% of districts that relied on file backups for their data recovered within a week, the same was true for 32% of those that paid ransoms. The report doesn’t explore the number of school districts which didn’t pay ransom demands and then had their confidential data leaked online.

The confidential nature of compromised data, and the potential damage of its public release, influence districts’ decisions to pay ransom, Elder said.

“This is highly confidential information, some of it can be harmful, and we’re educators: We like to take care of people,” Elder said. “But I do think sometimes we have to draw a hard line to manage our property. It’s a hard decision. I doubt there’s any single answer for anyone.”

Insurance appears to be a motivating factor in districts’ decisions to pay ransoms, Wisniewski said. In school systems with standalone cyber insurance, 56% of victims paid the ransom compared to 43% with broad insurance policies that included cybersecurity coverage. Ransom demands are often covered by insurance, Wisniewski said, and companies who have to pay off the claims are likely to have significant influence over which districts come across with the money.

“The only conclusion I can draw from that is the insurance companies think that paying the ransom is going to save them money because in the end the insurance company is on the hook for helping you recover,” he said, despite emerging data to suggest the contrary. “The insurance companies are constantly playing catchup trying to figure out how they can offer this protection because they see dollar signs while everybody wants this protection, but they’re losing their butts on it.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)