Schools and COVID, a Year Later: 12 Months After Classrooms Closed, 12 Key Things We’ve Learned About How the Pandemic Disrupted Student Learning

It was March 15, 2020 when Mayor Bill de Blasio announced the emergency closure of New York City’s schools amid skyrocketing coronavirus infections. (See our time capsule of what that surreal week felt like inside America’s largest school system). But I remember more vividly the chaos of Brooklyn two days prior, on Friday the 13th, when my family woke up to panicked social media posts reporting that a parent had tested positive at a school four subway stops away. It was 8 a.m. March 13 when we reversed course, unpacking our daughter’s backpack and calling the school to say she’d be staying home.

She wouldn’t return to a classroom until October.

Everything was normal last spring up until the minute it wasn’t, as the world seemed to stop on a dime and schools found themselves transitioning overnight to remote instruction. But while the great COVID pivot may have felt instantaneous, it took far longer to begin to grasp the consequences for students and families of these long-run closures.

Here at The 74, we’ve chronicled those consequences over the past 12 months via our new PANDEMIC hub (you can get our continuing updates delivered to your inbox by signing up for The 74 Newsletter). Now looking back through the seasons at which stories were most shared and widely circulated, a few obvious trends emerge about the evolving reality for students and readers’ top concerns.

Here are a dozen of the key lessons we’ve learned over the past 12 months about the students most impacted by the public health crisis:

New Study Reveals ‘Devastating Learning Loss’ for Youngest Children, Showing That Preschool Participation Has Fallen by Half During Pandemic — and May Not Improve in the Fall

Early Education: How much learning are preschoolers set to lose amid the pandemic? That’s the question the authors of a report were asking last summer, about the coronavirus’ impact on young learners. The National Institute for Early Education Research’s survey of roughly 1,000 families showed that even when early education programs offered activities such as reading a book or sending home math and science activities, most families didn’t participate. The fact that participation fell from 60 percent of young children to 30 percent suggests, as many experts have said, that distance learning for young children isn’t really learning. Meanwhile, reporter Linda Jacobson writes, researchers recommend that when preschool programs begin to reopen, leaders should make space available to the children least likely to have strong support for learning at home, and to make sure they are in the highest-quality classrooms. One researcher said New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio “should prioritize child care for parents struggling to keep food on the table, not Zoomers who can work from home.” (Read the full story)

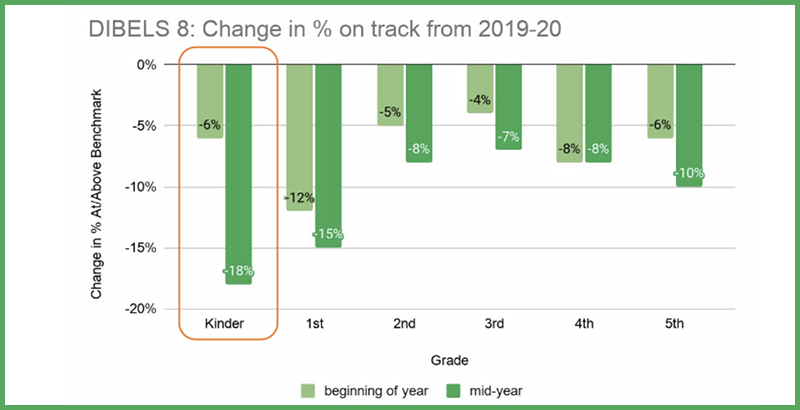

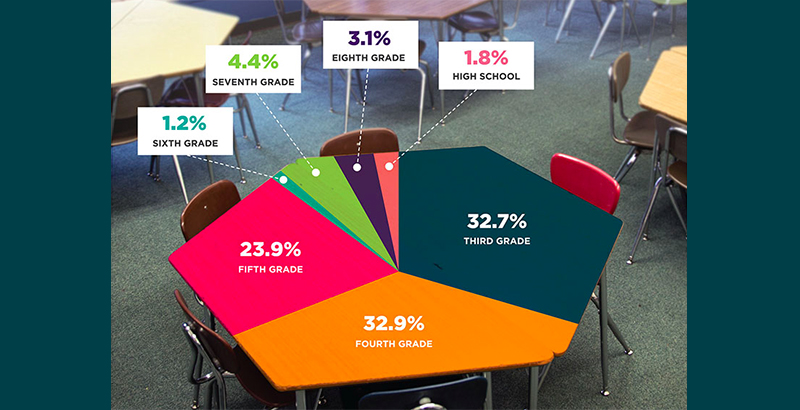

One Year into Pandemic, Far Fewer Young Students are on Target to Learn How to Read, Tests Show

Learning Loss: This year’s kindergartners and first-graders are almost 20 percent more likely to be off track in reading than their peers were last school year, before the onset of the pandemic, according to new data released in February from curriculum provider Amplify. While children struggling in reading would normally make up ground between the beginning of the school year and winter, the results from roughly 400,000 students show that teachers aren’t “seeing the bounceback” they normally would, said Amplify’s Paul Gazzerro. Experts said it’s important to double down with grade-level instruction and that K-1 provides a key window in which to close the gap. According to Amplify’s Susan Lambert, “We have a sort of once-in-a-generation chance to catch up these students.” Linda Jacobson reports. (Read the full article)

Federal Probes into Lack of School Services for Special Needs Students Reflect Nearly a Year of Parental Anguish, Advocates Say

Special Education: In the waning days of the Trump administration, the U.S. Department of Education’s civil rights office launched four investigations into whether schools failed to serve students with disabilities during the pandemic. As 74 contributor Jo Napolitano reports, the inquiries came as no surprise to many parents who have watched their children lose skills it took them years to build. The probes — covering the state school system in Indiana, as well as districts in Los Angeles, Seattle and Fairfax, Virginia — reflect “similar complaints from all across the country,” said Denise Stile Marshall, head of The Council of Parent Attorneys and Advocates, a group that works on behalf of children with disabilities. “Many parents are desperate and at their wits’ end.” (Read the full article)

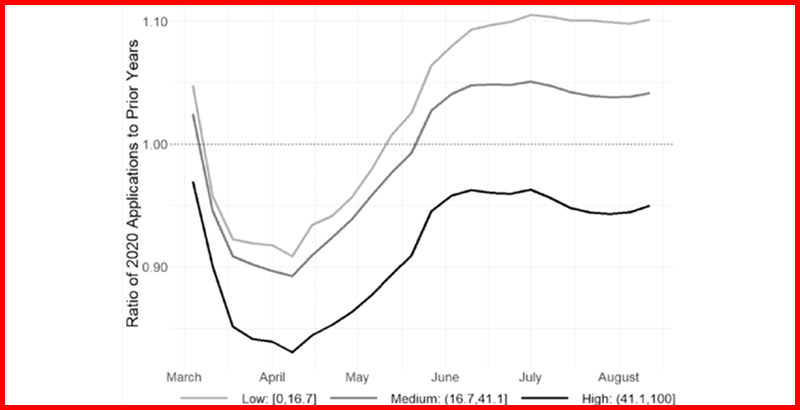

FAFSA Applications Fell After COVID — And For Many Incoming Freshmen, They Haven’t Recovered

College Enrollment: New research offers troubling findings about the pandemic’s impact on postsecondary education. According to an analysis of student data from California, the emergence of COVID-19 last spring led to a significant decrease in filings for the Free Application for Federal Student Aid. While the numbers eventually recovered for returning college students and those in graduate school, applications for incoming freshmen with no college experience were 21 percent lower between last March and August than in previous years. The decline was particularly evident in zip codes with higher percentages of Hispanic and African-American residents. According to co-author Oded Gurantz, a professor at the University of Missouri, the decision to even temporarily defer college enrollment after high school can be a significant one: “A lot of students who choose not to go in the short term — that ends up being a long-term decision because it’s very hard, once you’re out in the workforce, to go back to college,” he told reporter Kevin Mahnken. (Read the full article)

Youth Suicide: The Other Public Health Crisis

Mental Health: Brad Hunstable believes his son died of the coronavirus — just not in the way one might expect. As COVID-19 shuttered schools nationwide and put students’ social lives on pause, Hayden committed suicide just days before his 13th birthday. His father blames that pandemic-induced social isolation — and a fit of rage — for his son’s death. Though the national youth suicide rate has been on the rise for years, students say the unprecedented disruption of the last few months has taken a toll on their emotional well-being. Researchers worry that a surge in depression and anxiety could drive a spike in youth suicide. Sandy Hook Promise, which runs an anonymous reporting tool, saw a 12 percent increase in suicide-related reports in between March and October of 2020. The issue also became a political football ahead of last fall’s election, with President Donald Trump and others citing rising rates of depression and suicide as reasons to relax COVID-19-related restrictions on in-person classes. (Read the full article from The 74’s Mark Keierleber)

Rural Schools Have Battled Bad Internet, Low Attendance and Academic Decline Through the Pandemic. Now the Push Is On to Return Students to Classrooms — Safely

Rural Education: As schools across the country confront how to safely educate students in the midst of a global pandemic, rural districts face unique challenges. Issues such as diminished resources, race-based inequities, transportation and inadequate access to broadband are exacerbated in these communities, whether instruction is delivered in classrooms, online or both. As reported by Peter Cameron of Wisconsin Watch and The Badger Report — part of an ongoing series, “Lesson Plans: Rural Schools Grapple With COVID-19″ — rural districts are striving to move beyond the challenges of the fall semester and find a way to safely bring kids back to their classrooms this year. Read Cameron’s full report.

12 Months After Pandemic Closed Schools, 12 Million Students Still Lack Reliable Internet

Digital Divide: A year after the coronavirus shut down the nation’s schools, Eva Garcia’s children are among the 12 million students who either have no Wi-Fi or make do with short-term fixes to participate in remote learning. Her daughter became so stressed from getting knocked out of Zoom classes that her hair began to fall out. Linda Jacobson examines persistent barriers to closing the digital divide: lack of broadband in rural regions, inoperable devices and families without stable housing. There is growing political pressure to solve the problem, but still so far to go. “It’s frustrating watching the state and federal government work so slowly,” said Devon Conley, school board president in California’s Mountain View Whisman School District. “In the grand scheme of things, internet access shouldn’t be just for students. I think it’s a human right.” (Read the full article)

Research Predicts Steep COVID Learning Losses Will Widen Already Dramatic Achievement Gaps Within Classrooms

Achievement Gaps: In the days immediately following the pandemic-related closure of schools throughout the country, researchers at the nonprofit assessment organization NWEA predicted that whatever school looks like in the fall, students will start the year with significant gaps. Now, they are warning that the already wide array of student achievement present in individual classrooms in a normal year is likely to swell dramatically. In 2016, researchers at NWEA and four universities determined that on average, the range of academic abilities within a single classroom spans five to seven grades, with one-fourth on grade level in math and just 14 percent in reading. “All of this is in a typical year,” one of the researchers, Texas A&M University Professor Karen Rambo-Hernandez, told Beth Hawkins in June of 2020. “Next year is not going to look like a typical year.” (Read the full article)

Lifeline: How Bilingual Learning Pods Are Helping English Language Learners Navigate Classes During the Pandemic Without Teachers or Peers

English Language Learners: In Ohio, the Cleveland school district gave students computers and internet hotspots to take online classes this school year, but some students, particularly English learners, needed more help. For many of these students, following teachers and picking up nuances of lessons and assignments was too much. “To understand what the teacher is saying, I really have to focus,” said Gibrielys Delgado, a high school sophomore originally from Puerto Rico. But community groups stepped in to offer bilingual support at learning centers, places where students can take their online classes during the day. For some, having simple language help right there in the room made a huge difference. Natasha Arroyo, who runs one of the city’s bilingual centers, told Patrick O’Donnell she sees students go from very low F grades to passing with just a little support. “When I see… ‘Oh, we made it to a C or a B,’ that’s how I know we’re doing what we need to do as a learning pod,” she said. (Read the full article)

‘I Had No Other Option.’ Teens Balance Zoom Classes and Fast-Food Jobs — Sometimes at the Same Time — to Support Struggling Families

Economic Hardship: Listening to Zoom classes while blending smoothies and cramming homework into breaks between customers are among the ways teens are bending the rules of distance learning to help their families survive. “It’s not just to pay their cell phone bill. For some of them, it’s like, ‘I need to help my family pay the rent,’” a college and career counselor told reporter Linda Jacobson. One Los Angeles student became the primary earner in her family when both parents contracted COVID-19 and had to quarantine. While some teens are determined to manage their added responsibilities without falling behind, others say they’re less motivated to keep up with remote classes. And counselors walk a fine line between being firm and showing empathy for students whose families are struggling. As one said: “I respect the hustle.” (Read the full article)

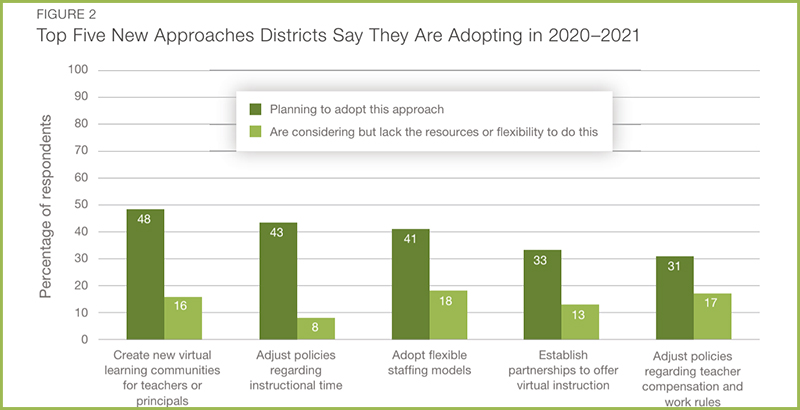

Analysis: Survey of District Leaders Shows Online Learning Is Here to Stay. Some Ways of Making It Work for Students Beyond the Pandemic

Remote Learning: A new, nationally representative survey of district leaders shows that remote coursework is here to stay — and school systems will have to apply the lessons from their forced experiments with virtual learning during the pandemic to better adapt. The first survey conducted through the new American School District Panel shows 1 in 5 districts are considering, planning to adopt or have already adopted a fully online school in future years, and 1 in 10 has adopted blended or hybrid instruction, or plans to. Of all the pandemic-driven changes in public education, the creation of virtual schools was the one that the greatest number of district leaders anticipated would continue into the future. Remote instruction is a fundamentally different task than what school districts are designed for, as school systems nationwide learned when they were forced to suddenly close last spring. But, write contributors Heather Schwartz and Paul Hill, lessons from six case studies demonstrate how districts can use their pandemic-related momentum to make online learning a common staple of public schooling. (Read the full piece)

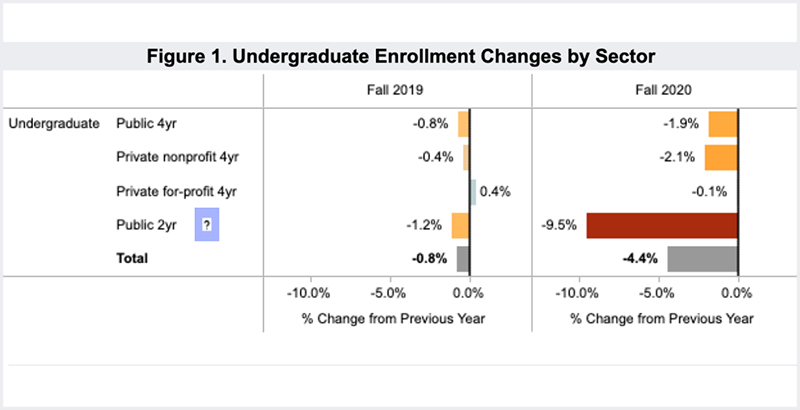

New Data: Sharp Declines in Community College Enrollment Are Being Driven By Disappearing Male Students

Community Colleges: That the pandemic was going to hurt community college students more than their four-year college counterparts was not unexpected, given that community colleges are more likely to enroll low-income and first-generation students whose paths are already more challenging. What new data from the National Student Clearinghouse reveals is how much that dropoff is being driven by male students, particularly Black male students. The number of Black men enrolled in community college fell 19.2 percent between fall 2019 and fall 2020, followed by 16.6 percent for Hispanic men and 14 percent for white men. Author and 74 contributor Richard Whitmire, who has written extensively about college completion, talks to educators and others concerned that we may be looking at a “lost generation of males from low-income and working-class families.” (Read the full article)

See Our Photo History: 52 Photos, 52 Unforgettable Weeks for Students & Schools

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)