School Without Walls: Program Created by 110-Year-Old Black Church Becomes ‘Lifesaver’ for Wisconsin Parents

By Zoë Kirsch | March 1, 2021

This piece is part of “COVID Warriors: How Educators Are Saving the Pandemic Generation,” a two-week series produced in collaboration with the Solutions Journalism Network that explores what educators, schools, and districts are doing to prevent an entire generation of students from lost learning and its lifetime of consequences. Read all the pieces in this series as they are published here. Catch up on all of our solutions-based coverage here.

It was another long morning in early September, and, like countless other parents, Jodie Pope-Williams, an academic advisor at Madison Area Technical College, found herself in the same place yet again: tired, anxious and crying, trying to balance her own remote work with her son’s virtual learning.

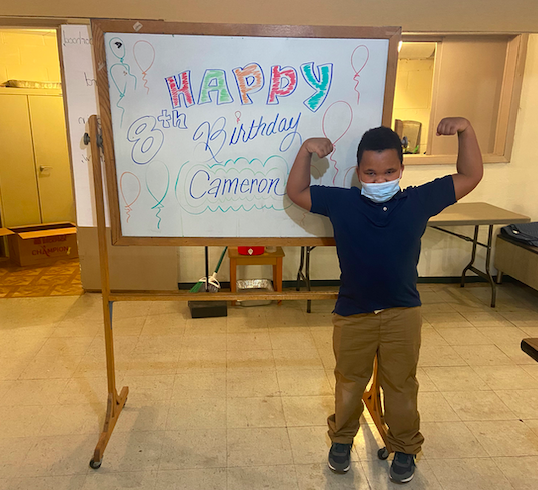

Eight-year-old Cameron attends One City Schools, a local charter program which has offered students in-person learning since the fall. Pope-Williams and Cameron’s father like the school, but both have high-risk family members, and their son has Type 1 diabetes — factors that caused worry about sending him back.

In March, when parents were thrust into the so-called “new normal,” Pope-Williams had been able to keep her chin up: working from home and online learning felt fresh well into April and May, she said. Then the summer rolled around, and things took a turn for the worst. She watched as Cam, a quick-witted, outgoing child, grew despondent.

“It didn’t take me long to see that him staying engaged in classwork was taking a hit,” she said. Pope-Williams thought about the school-to-prison pipeline, and about how, in just a year, Cam would be in the third grade, the year reading scores become predictive of the likelihood that a child will graduate. She reshuffled her work schedule to make more time to support him through school. But most days, it didn’t feel like enough.

That was all before that Tuesday in September, when a visit to her Facebook homepage changed everything. Pope-Williams came upon a notification from Mt. Zion Baptist Church, the 110-year-old congregation she had been a part of since the age of 12. The largest Black church in the Madison area, Mt. Zion sits on the city’s Southside. To many congregants, including Pope-Williams, it isn’t just a place of worship: it’s family.

The Rev. Dr. Marcus Allen and newly minted youth minister Richard Jones Jr. planned to give families free access to an academic support program called School Without Walls, the announcement read. The offering would run three-and-a-half hours every morning, five days a week. For Pope-Williams, School Without Walls presented an attractive alternative to her son’s school: it was a place she could trust, a place that felt like home.

“I know they’re going to support him, in terms of health and academically,” she said. “It was a lifesaver for us.”

Parents with children in School Without Walls told The 74 that the program brought them relief and their children academic help, at a time when they couldn’t find those things elsewhere. Across the country, some Black families have expressed reluctance over sending their children back to school. Their wariness reflects the disproportionate toll the virus has taken on communities of color, and a mistrust of the public schools, which long predates the pandemic, but has intensified during it. In contrast, African-American churches have been havens for decades.

In a time of political instability, global disruption, and a complex, virulent disease, one solution to some of these parents’ problems emerged from something simple: human relationships forged at a faith-based institution.

“It makes me want to help more because of that community aspect — that piece is real,” said parent and church member Faleshuh Walker, who works at School Without Walls and sends her children there. “They really change lives, they really care … If I was hungry, I know they’d knock on my door [to give me] food. If I was cold, they’d find somewhere for me to go. It’s bigger than just the school piece. It’s life.”

“The work we’ve done in the community allows parents to feel comfortable sending their children to our church, even when they won’t send kids to school.” —The Rev. Dr. Marcus Allen, pastor Mt. Zion Baptist Church

The church’s prominent role in the city and the involvement of renowned University of Wisconsin-Madison-based education scholar Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings — also a longtime Mt. Zion congregant — helped School Without Walls attract a range of partners; the United Way, anonymous donors, and Dane County Human Services all contributed staff funding. Edgewood College, a local liberal arts school, supplied and paid for several undergraduates studying education to be classroom assistants. And the Madison Metropolitan School District provided meals, so the kids could have free breakfast, lunch and a snack every day.

School Without Walls is an offshoot of a summer learning and enrichment program that Ladson-Billings and Jones launched back in June to help 3rd- and 4th-graders confronting pandemic-related learning loss.

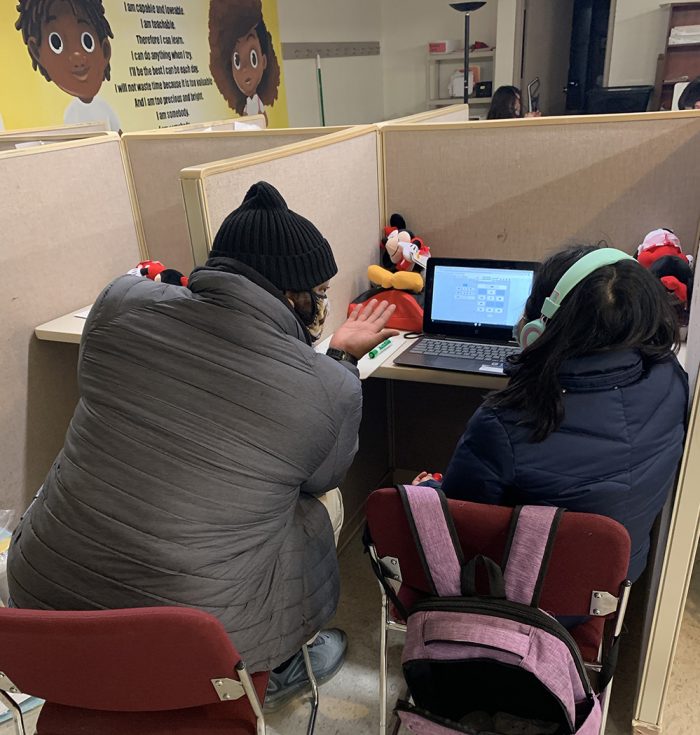

“We knew the [summer slide] would be hyperextended because of COVID and the abrupt switch to virtual learning in the middle of the semester,” Jones said. “Consistency [with remote learning] was a problem we saw last spring. And we saw it in September when schools started back up: communication problems, tech problems. We’re here to aid that.”

Since the fall, he’s been in regular contact with counselors from nearby schools, including Lincoln and Midvale Elementary, in order to recruit the children who need the program the most. “We’re looking for the kids who wouldn’t go to class if they weren’t here, wouldn’t do their homework, wouldn’t show up,” he said.

“A lot of parents are hesitant to even send their kids to school,” added Rev. Allen. “These parents have been willing to send them to our program …The work we’ve done in the community allows parents to feel comfortable sending their children to our church, even when they won’t send kids to school.”

Shaking kids ‘out of the screen’

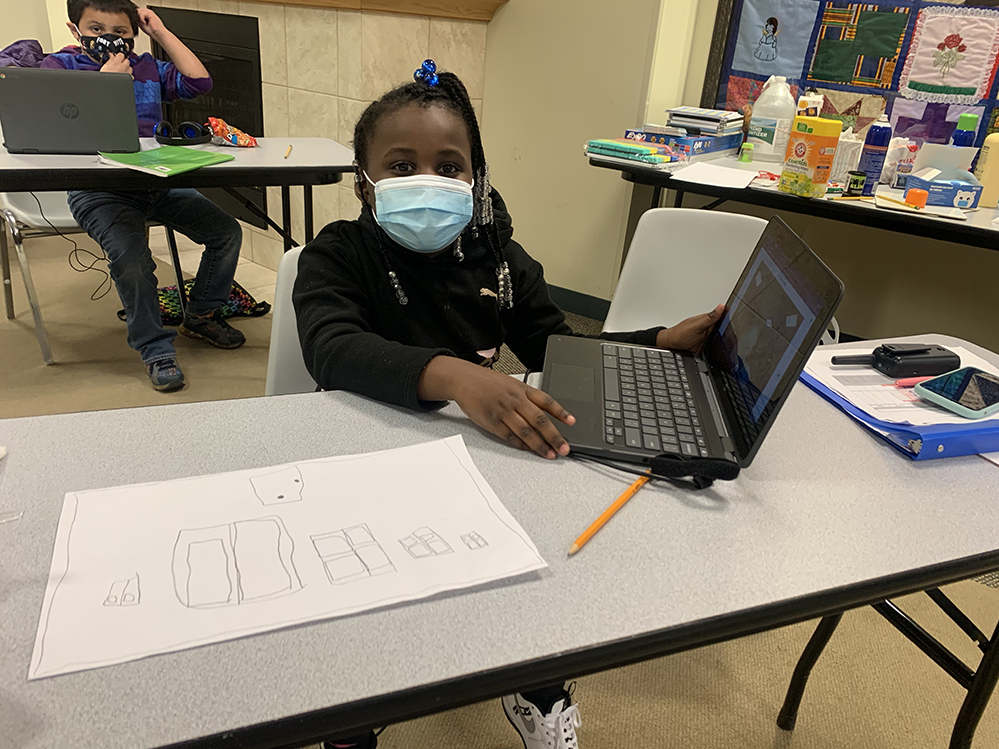

School Without Walls’ robust community partnerships and financial support translates into an enviable staff-to-student ratio: eight tutors for a maximum of 30 students a day, ranging in age from pre-K through 5th grade. Since the start of the pandemic, the initiative has seen about 70 students come and go, Jones said. For some, it’s been a stepping stone in the journey back to school itself.

Many of the program’s staff have longstanding ties to the church, including Walker, who, prior to the pandemic, volunteered in its afterschool learning program. Since the fall, she’s been working at School Without Walls from 9 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. Monday through Friday. Every morning, she wakes up with her three children and prepares them for the day. Her 13-year-old daughter goes to stay with Walker’s sister, while 8-year-old Nathaniel and 5-year-old Naqari attend School Without Walls with their mom.

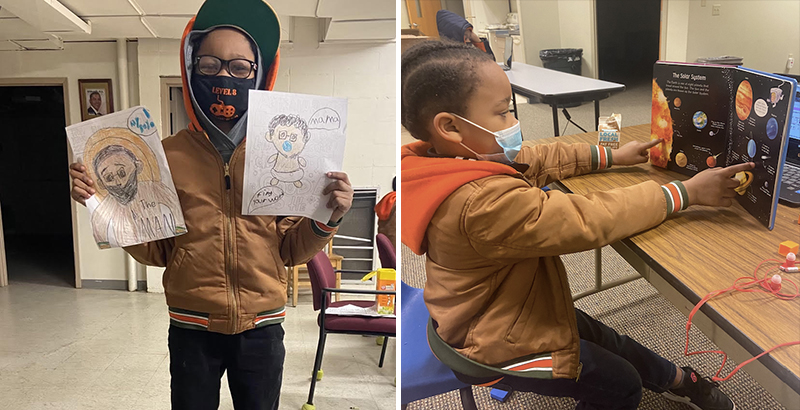

While Walker spends part of her day assisting kids with their academic work, her true passion lies in helping them transform their leftover energy into art. She oversees the creation of paintings, book illustrations and self-portraits. On a recent day, she encouraged a student to paint a picture of a bucket, and the “kind words” that go into it. On other occasions, she’s invited children of color — the program is predominantly kids of Black, Latinx and Hmong origin — to draw their favorite cartoon characters in their own nationalities.

“They just go create, which they would’ve never done, if I had let them stay on their tablets,” she said. “We find ways to shake them out of the screen for a little while.”

That effort meant everything to Pope-Williams who, as the weeks dragged by, watched Cameron perk up. Once, he came home from School Without Walls with a Power Ranger drawing he had made. Another time, he presented her with an extracurricular worksheet he had filled out about Black History Month.

Pope-Williams and Walker both said that, in a world where Black men constitute just 2 percent of the American teaching corps, Jones’s presence was an added bonus.

“I see value in my son seeing himself in these types of roles,” Pope-Williams said. “Most Black men in Wisconsin that are in school districts are in special ed or disciplinary roles. To have a Black man leading the program is a great representative for my child.”

“Richard is a wonderful example of a man for my boys,” agreed Walker. “I appreciate them seeing all types of men, so they can understand this is normal. It’s cool to be smart, to love God, to help people.”

Jones knows Billings, the professor, through his parents, who moved to Madison in 2004 for work. “I refer to her as my mom,” he said. “I see her as a role model, advisor, support system.” When she approached him with an idea for academically supporting kids during the pandemic, he was happy to step up.

Looking for improvement, not perfection

Districts that want to start a program like School Without Walls should consider leadership one of three key ingredients, Allen, the pastor, said. While many churches have empty space most of the week, “You need a great leader in place that’s diligent, to make things happen,” he explained. The other key elements are funding and other kinds of support from community partners.

“We’re being intentional about helping our Black students close the [achievement] gap,” he said. “But it’s also the responsibility of the community to engage our students to provide space for kids to learn. It’s the responsibility not just of the school district, but also of the community, to step up and do what needs to be done to make sure the kids are getting what they need.”

The Rev. Dr. Marcus Allen, pastor of Mt. Zion Baptist Church, and Jon Anderson, founder and executive director of the Collaboration Project, talk in February about financial support the Collaboration has pledged to School Without Walls (Facebook / Mt. Zion Baptist Church)

For Allen and Jones, meeting that goal wasn’t without obstacles. Their initial vision was to have five programs like the one at Mt. Zion, bound by a shared mission: literally, a “School Without Walls.” But bringing that concept to fruition wasn’t possible, Allen said. The building owners, operators and managers they approached were uncomfortable offering their spaces up to people they didn’t know personally during the pandemic.

“So we went with what we had: Mt. Zion,” Allen said.

He added that he’s seen the program’s efforts reflected in students’ grades during COVID, even if on a modest scale.

“We can’t expect perfection during these times — not A+s, but passing grades,” he said.

In a recent Zoom call, families around the city said that they, too, want a resource like School Without Walls, according to Pope-Williams. But given those parents’ work schedules and the church’s location, they haven’t been able to get there.

For Monica Warren, the program is so valuable that her family plans to relocate from their home, one exit away from Mt. Zion off the Beltline, to a house that’s closer, about a 15-minute walk.

Her son, 10-year-old Jeremiah, has been attending School Without Walls since the fall. While he misses being at Frank Allis Elementary — his peers, his teacher and his favorite class, math — he has friends at the program. They’re kids he knew long before COVID, he said, friends from church.

Before School Without Walls existed, Warren brought Jeremiah to Edgewood College, where she works as a cook, making food for students on campus.

Warren’s a relative newcomer to Madison: she arrived there from Baltimore in 2016. After joining the Mt. Zion community two years later, she quickly became involved, attending services regularly and volunteering at the weekly breakfast ministry, where she’d whip up plates of bacon, eggs, sausage, grits, hard boiled eggs, and fruit for fellow congregants.

All three mothers are now facing a challenging decision about their kids’ education, as winter melts into spring. After being remote all year, Madison public schools recently announced a return to buildings for the city’s youngest learners, starting March 9.

School Without Walls will remain open for the rest of the school year, and soon, Jones will learn whether his team received a new grant from the district. According to Allen, the congregation intends to build a new community center to house School Without Walls and its other social services, including a food pantry and a mental health center established in October.

Warren doesn’t know when she’ll send Jeremiah back to school because it isn’t clear when the district will reopen buildings for kids his age. Walker’s considering homeschooling her kids post-pandemic, encouraged by the time she’s spent with them at School Without Walls.

As for Pope-Williams, a few weeks after the program celebrated her son Cam’s 8th birthday on Jan. 19 with a cake dropped off by his dad, she sent him back to his charter school.

“Seeing that School Without Walls was able to keep the kids safe, and that people were taking it seriously, I could look at sending him back,” she said. “I can’t say it enough: during this time, it really saved me.”

Lead Image: A mural that parent, church member and School Without Walls staffer Faleshuh Walker painted for the program at Mt. Zion Baptist Church. (Faleshuh Walker)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter