Reading, Writing & Healing: Amid Widespread Anti-Immigrant Sentiment, an Ohio School for Refugees Emphasizes ‘Creating a Childhood’

Over the next several weeks, The 74 will be publishing stories reported and written before the coronavirus pandemic. Their publication was sidelined when schools across the country abruptly closed, but we are sharing them now because the information and innovations they highlight remain relevant to our understanding of education.

Columbus, Ohio

Among dozens of people packed into a dark-paneled courtroom on a rainy Halloween are Anita Maharjan, a Nepalese immigrant, and the three dozen or so sixth- and seventh-graders she teaches art.

Maharjan is one of 65 new citizens attending a naturalization ceremony with family and friends. The ceremony, starting with an unofficial rendition of “God Bless the U.S.A.” and moving into the more official introductions, the swearing in and the Pledge of Allegiance, is an important experience for the students, and not just because it’s a way to see civics in action. All the students at Maharjan’s school, Fugees Academy, are refugees, and they will go through this process themselves someday.

Maharjan, who came to Ohio to study art, sees herself as a bridge for her students.

“I have been in their shoes,” she said.

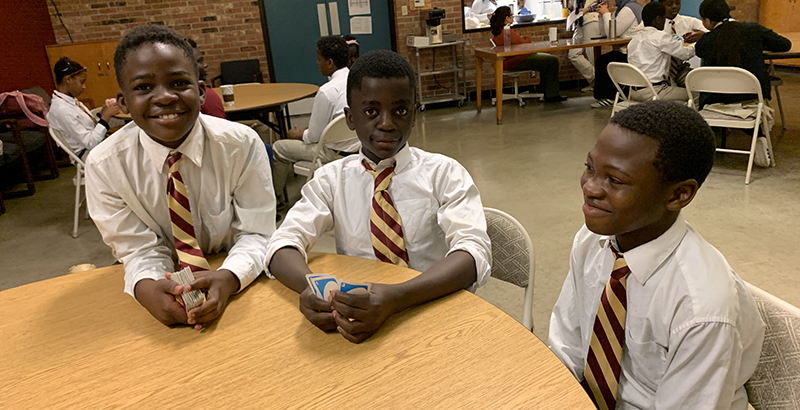

In many ways, the students at Fugees, housed in a church in the northern part of the city, are the same as any middle schoolers: They flirt by hitting, are cutthroat in before-class UNO games, and are curious about a visiting reporter’s age but aware that it’s not polite to ask a woman that question.

But the students — from countries including Nepal, Burma, Congo and Iraq — also come to school with challenges totally outside the experience of the typical Columbus tween. Some arrived directly from refugee camps overseas where they received little, if any, formal education; most have been in American public elementary schools that didn’t adequately meet their needs. Lessons at this middle school often involve basics like days of the week and shapes.

Staff at the Academy, a private school that students attend with vouchers, have a heavy load. They have to accommodate students’ vast academic and social-emotional needs while preparing them academically in a political climate that’s often hostile to immigrants. For example, the soccer team from the school’s sister campus outside Atlanta is sometimes greeted with a Confederate flag and chants to “go back” to their home countries.

“I truly believe that the majority of the country loves our kids, but I don’t know how to show it to them,” founder Luma Mufleh told The 74.

An immigrant herself, Mufleh came to the U.S. from Jordan to attend college, but as a lesbian, it was too dangerous for her to return home. She eventually applied for and was granted asylum in 1999. Mufleh and Fugees attracted widespread media attention after she was named a CNN Hero in 2016 and gave a much-viewed TED Talk in 2017.

The school grew out of her efforts to help coach immigrant boys in soccer and assist them with their homework in 2004; two year later, she started an organized team and mentoring program, with the school’s original campus in Atlanta opening in 2007. It has now graduated three classes of students: 100 percent got diplomas, and 74 percent are enrolled in college, with the rest working or enrolled in job training or apprenticeship programs, according to Emily Futransky, the school’s chief academic officer.

The Columbus campus opened in 2018 and has a sixth- and seventh-grade class, with plans to add grades as the students age. Another site is expected to open in Cleveland. Future expansions will depend on state school choice policies.

These policies have worked well for Fugees in the past. In Ohio, the schools are funded through a long-standing voucher program that originally targeted students attending failing public schools but that lawmakers expanded in 2013 to low- and middle-income families. The original Georgia campus also started as a private school but ran on fundraising. It is now in the process of converting to a charter due to a state law that allows schools to weight their lottery to give preference to English language learners and those from low-income families. The change would allow the school to continue to serve the same refugee students it has in the past.

‘We fill in the blanks’

For the students, and the trauma many of them carry, “the first concern is creating a childhood,” Futransky said.

Teachers are trained to address students’ experiences, which range from hunger and loss of family members to a general sense of insecurity rooted in the often-precarious journeys they made with their families to the U.S.

They’re careful, for instance, about when and how to address the students’ past experiences, as many have compartmentalized the painful memories of life before coming to Fugees.

“Many of them are masters of their own survival,” she said.

Given the chaos many of them fled, the students long for consistency — a need the Academy meets through a standard schedule for each school day and throughout the week. Staff work to ensure that every student can identify at least one adult they feel comfortable coming to in times of crisis. But in lieu of traditional counseling, yoga and soccer (all students play) give them a physical outlet to process trauma.

“These are both ways that we can help students develop a strong mind-body connection and have an outlet that does not ask them to process in a way that’s upsetting,” Futransky said.

Moving from survival to a more traditional American childhood also means activities like a spring break camping trip, a visit to the zoo and, on this particular Halloween day, trick-or-treating. It’s an experience wildly outside what most of them have lived through and a much-anticipated annual tradition.

The school always creates costumes around a theme. This time, it was school supplies.

Several boys dressed as scissors, with large cardboard cutouts around their necks. Many of the girls were bottles of glue — Elmer’s logos on their T-shirts, skirts made out of ripped-up white plastic bags, and topped with orange conical hats. Students also dressed as notebook paper, calculators and paint sets.

The traditional outdoor trick-or-treat was ultimately canceled due to weather. Staff instead set up stations in classrooms for students to walk around and collect candy. Students were a little upset at losing the traditional experience, but that dispelled pretty quickly as their haul of Snickers, Tootsie Pops, Starbursts and Twix propelled a collective sugar high.

Though there’s plenty of fun, the academics at Fugees are rigorous. They have to be, given the gaps in many students’ learning. Those who come straight from refugee camps, and those who transfer from public schools, are put in age-appropriate, not level-appropriate, classes, Mufleh said.

Ajaya, a seventh-grader, described having to take Spanish class even though “I didn’t know how to speak [English].”

That means staff end up packing the equivalent of kindergarten through eighth grade into just three middle school years, Mufleh said. Despite the necessary catch-up, the Fugees students are making gains. The seventh-graders, at both the Columbus and Atlanta campuses, exceeded projected growth rates on the commonly used NWEA MAP test by 222 percent in math and by 104 percent in reading in 2018. Historically, about 80 to 85 percent of students are on grade level by the time they get to high school, she added.

Classes emphasize English, reinforced with music and art that help with “rewiring the brain” and learning language, Mufleh said.

Many of the staff are immigrants or refugees themselves. Reflecting the customs of their home countries, students call teachers by their first names, Maharjan, the art teacher, said.

The staff often ends up tackling much more than traditional classroom activities. They explain American traditions, like trick-or-treat and Thanksgiving, and also help navigate the constant swirl of political news and rumors.

They had to help clear up misconceptions about food stamps and other public assistance when the Trump administration earlier this year said using those benefits would be a mark against those seeking green cards. (Refugees are exempt.)

“Wherever there’s a need, we fill in the blanks,” Maharjan said.

The staff wasn’t always so diverse, having long attracted mostly white female teachers.

To guard against potential bias, the school has started advertising with immigrant organizations, and an intern removes names from résumés before staff screen job candidates. The staff also works with candidates to get necessary certifications. The two math teachers in Columbus, for instance, both have master’s degrees from foreign universities that have strong academic reputations but that don’t meet the standards for American teacher certification.

“The kids need to see and hear people who look like them. That’s motivation,” Mufleh said. “They’re seeing their own experience be successful.”

Harsh climate for refugees

Despite the staff’s best efforts to create a real childhood for the children, adult political concerns inevitably creep in.

Students at the school’s Georgia campus were afraid they’d be deported after the election of Donald Trump, who during the 2016 campaign vowed a “total and complete ban” on Muslim immigration.

That, of course, didn’t come to fruition, but three students at the Columbus school ultimately had family members affected by the ban. Several staffers mentioned rumors of a “Kill a Muslim Day” that circulated on Facebook a few years ago that affected students at the Atlanta campus.

“The hard part is, I like to be preventative and prepared, and I feel I can’t be,” Mufleh said. “Every day I wake up, I check my Twitter feed. I used to check it to see what’s going on in the countries the kids are from, to be prepared for the moods in the building. And now I have to check someone else’s Twitter account to see what is on social media that our kids are going to be affected by.”

Everyday interactions can also be fraught. For instance, school leaders are careful when selecting which neighborhood the kids visit for trick-or-treating.

Staff are also careful not to release the specific location of either of their campuses, both housed in churches, and they asked The 74 not to publish them.

Mufleh’s time in the spotlight following her CNN Hero award attracted attention of all kinds. There were threatening voicemails and supportive calls from people wanting to learn more about the organization. But even in those cases, she said, some treated the school like a zoo, visiting without an appointment to see children whom they appeared to view as curiosities.

So far, the kids aren’t feeling it: Several, when asked their favorite thing about school, answered that they feel safe.

“It’s hard because you want to get out there, you want to tell the story, but if every kid in here says they feel safe,” the school owes it to them to maintain that sense of security, Mufleh said.

Despite the harsh political climate for refugees — the Trump administration reduced refugee admissions to just 18,000 in 2020, a record low for the past three decades and nearly 100,000 fewer people than President Obama had planned to admit in 2017 — Mufleh sees a need for Fugees schools elsewhere, and new choice models to help fund them.

After the Cleveland expansion, school leaders are eyeing moves to Indiana and Florida, where there are favorable voucher programs, and Missouri, where there is a favorable charter law.

Ultimately, Mufleh wants to work herself out of a job, something she can only do if public schools are serving refugee students well.

She’s willing to share her methods for teaching, cultural competency and communication with parents — but so far, no one has been interested, she said: “I just wish more people were open to that.”

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

;)