Problems With NYC’S Gifted and Talented Program Shared Across the Country — Along With Fears for Gifted Ed’s Future

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

New York City’s elementary school gifted and talented program, long criticized for its stark failure to include Black, Hispanic and other students, might win a reprieve from the likely incoming mayor. But the problems that led to its potential closure — how best to serve advanced learners without being exclusionary — still bedevil school districts across the country.

The program’s very existence at the national level has grown increasingly politically polarized in recent years, with many progressives pushing for its dismantling and conservatives arguing for its preservation: In the nation’s largest school system, which serves nearly 1 million students, politicians, not educators, are fighting over its future.

What will happen to New York City’s program is uncertain: outgoing Mayor Bill de Blasio proposed abolishing its controversial testing of 4-year-olds and instead offering accelerated learning to all of the city’s 65,000 kindergarteners next fall compared to 2,500 such children today. Eric Adams, de Blasio’s all-but-certain successor, has said he wants to keep the gifted and talented program, but create his own version whose eligibility requirements and delivery methods he hasn’t specified.

To better understand what other school systems are doing to identify and serve gifted children, The 74 asked more than 20 large and diverse districts across the nation about their screening processes, delivery methods and racial breakdown of participants. Ten replied, including Los Angeles Unified School District, Fairfax County Public Schools in Virginia, Florida’s Orange County Public Schools and Cypress-Fairbanks Independent School District in Texas.

We also queried experts who have spent years assessing gifted programs’ efficacy. And while there are strong differences of opinion as to the programs’ merit, many in the field agree that the nation’s approach is scattershot and delivery is too often ineffective.

If gifted and talented education in younger grades is to survive, it will have to change.

“There is a lot of rethinking of these more traditional models and some recognition that they don’t work so well for the kids that are in them,” said Jason A. Grissom, professor of public policy and education at Vanderbilt University.

Grissom found, after studying nearly 13,000 kindergarten children across the country for six years starting in 2011, that students showed only modest gains in reading and math in the years of their participation in gifted and talented programs. They showed no change in the frequency with which they report to work hard, pay attention and listen in class, among other factors.

And the results were worse for Black and low-income students: They did not appear to benefit academically, on average, possibly because their schools’ offerings were less robust than those of their wealthier peers.

Yet these programs have many supporters. Dina Brulles, who serves on the board of directors for the National Association for Gifted Children, said her organization was “devastated” to learn New York City might no longer have a gifted and talented program, a move that outraged many parents who believe it’s their child’s only path to a quality education.

“We know these kids need something different,” Brulles said. “These students cannot be challenged in a regular classroom with someone who does not have the training or resources.”

The problem is solvable, she said. But schools must let go of outdated approaches.

“A lot of districts have the same programs for 10, 20 or even 30 years and look for a kid to fit in it,” said Brulles, who is also the director of gifted education in the Paradise Valley Unified School District in Arizona. “I take the opposite approach. I look for the potential, group these students together and find out what they need.”

Sandra Kaplan, professor of clinical education at the University of Southern California, bristles at the notion of dismantling gifted education in younger grades, saying some children are simply more capable than others and should have their interests recognized. An expert in the field who has worked as a consultant for school districts and state departments of education around the country, she said teachers should be on the look-out for more-abled students as soon as they enroll.

“I want to start at preschool,” Kaplan said, adding that classrooms should be rich with materials meant to spark kids’ interest, much like a museum. “It is a teacher’s responsibility to provide an environment where kids can demonstrate what they know.”

Much of the model she suggests relies on teachers’ observation of students. She balked at the idea that such a method seems inexact and might exclude some children.

“There is a subjective element in all evaluation,” she said.

Nearly all of the school districts that responded to our survey have opted for universal screening, testing all students in younger grades for possibly entry to their gifted and talented programs in effort to sidestep the selection bias of teachers, which has long led to the marginalization of Black, Latino and Native students and those from low-income families.

But even this has not guaranteed equal access.

Fairfax County Public Schools conducts universal screening in first and second grade, but there is another pathway — it consists of parent referrals, appeals, requests for re-testing and procurement of outside exams — “for those who know about it,” according to a 2020 report.

That second, alternative route, “inserts a form of assessment bias, similar to traditional uses of teacher or parent nominations,” meaning that only some parents are aware of and take advantage of this work-around.

Los Angeles Unified was under scrutiny from the Office for Civil Rights for years because of the lack of Black and Latino students in its gifted programs: the case was closed in November 2019 after the country’s second-biggest district enacted several measures to include them.

Some 3.3 million children participated in gifted and talented education nation-wide in the 2017-18 school year according to The Office for Civil Rights in the U.S. Department of Education. Records from that time, which reflect the most recent data, show 58.4 percent were white, 18.3 percent were Hispanic or Latino, 9.9 percent were Asian and 8.2 percent were Black.

Students with disabilities made up 2.8 percent of the total and English language learners comprised 2.4 percent.

Grissom found, in a 2019 study, that children in the top 20 percent of the socio-economic status distribution were seven times more likely to receive gifted services than those in the bottom 20 percent.

The inequity remained even for those at the same achievement level: A child at the top income bracket was two to three times more likely to participate in gifted programing than a child at the bottom, even when their academic performance was the same.

And the tools used to determine students’ eligibility for gifted services — plus their expected performance on those measures — vary from one district to the next. The 10 districts that responded to our survey listed five different assessment exams among myriad other qualifications for students.

Third-, fourth- and fifth-graders at Clark County School District in Las Vegas, Nevada, must score at or above the 98th percentile on two commonly used entrance exams, the Naglieri Nonverbal Ability Test Third Edition or Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test Second Edition. They can also qualify if they earn at least 15 points on a combination of other factors, including testing.

Conversely, Baltimore City Schools changed its gifted and talented admissions requirements eight years ago in order to include a far greater swath of children: Any student who scores in the 73rd percentile on that same Naglieri test administered to kindergarteners is automatically enrolled and also must be provided with an Individualized Learning Plan — a sort of gifted version of the Individualized Education Program required for special education students, which might include advanced coursework or guidelines for an independent study program.

Prior to the switch, only 1,675 of the district’s students — it does not have data specific to elementary schools — or 1.97 percent qualified for gifted services in math and English language arts. By the end of the 2020-21 school year, 5,238 students, or 7.4 percent, had been identified, all while overall district enrollment shrank during the prior eight years.

Dennis Jutras, coordinator of gifted and advanced learning in the school system, said he’s proud of his district for holding onto the program. Baltimore schools serve nearly 78,000 children. More than 75 percent are Black, 14 percent are Hispanic and 58 percent hail from families with low income.

“We have codified universal screening, mandated individualized learning plans … and stated unequivocally that these students exist in all our schools and must be deliberately supported,” he said. “Gifted learners are atypical learners. To force them to adapt to a one-size-fits-all model of learning is inequitable — and doubly so when we’re talking about students of color and/or under-resourced communities. We would never treat other atypical learners in this fashion.”

Other school systems have taken an even broader approach: Some 86 percent of third- through 11th-grade students in Charlottesville, Virginia have been identified as gifted after a policy change that resulted in relaxed screening standards.

Paradise Valley Unified School District in Arizona uses universal screening to assess young children at all of its Title 1 schools. But it identifies gifted students by comparing them only to those children within their building rather than to the district at large, a tactic that could pit them against far more affluent kids.

Paradise Valley offers 14 different means to serve advanced learners, dividing participants into numerous groups based on their needs. Its “uniquely gifted” program serves children who need special education services and also have high intellectual abilities: Many have autism.

It has also made strides in including another historically overlooked group: English language learners. While the talents of students with special needs might be revealed during IQ and other tests of their ability, teachers often underestimate the intellectual abilities of children who do not yet speak English. Nearly a third of Paradise Valley’s students are Hispanic and 6 percent are English language learners.

“If we don’t take those measures, we are going to miss them,” Brulles said. “Those are the kids who worry me the most, the kids who have high potential but are being underserved.”

In addition to differences in screening and grouping students, there is also tremendous variation in how services are delivered, even within the same district. Children in Orange County Public Schools in Florida receive gifted services in one of four ways: Some study core subjects alongside only their gifted peers while others attend gifted class for a specific subject area.

Many districts are turning away from the traditional model of pulling children out of the classroom for enrichment and instead call for them to learn alongside their peers with their teachers providing more advanced materials, lessons and guidance for the selected few.

While this technique, called differentiated instruction, might be preferred, it’s often poorly executed by teachers already struggling to meet the needs of an intellectually diverse student body. A push in this direction might mean a slow death for this controversial program.

Differentiated instruction is what Mayor de Blasio, with just months left in office, proposed in place of funneling a small sliver of kindergarteners into advanced programs. But to train thousands of city’s teachers to serve gifted learners in every classroom is an effort that would require a tremendous financial investment.

“We don’t do differentiated learning properly,” Grissom said. “Teachers are able to do it to some degree, but not the degree needed to meet kids three grade levels ahead of the standard.”

And the qualifications for those teaching these children varies from one state to another.

Gifted students in Texas’s Cypress Fairbanks Independent School District receive differentiated instruction from teachers who’ve completed a minimum of 30 hours of required training in gifted education.

Paradise Valley requires a minimum of two college courses on the topic or 90 hours of professional development in the form of workshops and conferences, but encourages most of its teachers to take five college classes or complete 180 hours of training.

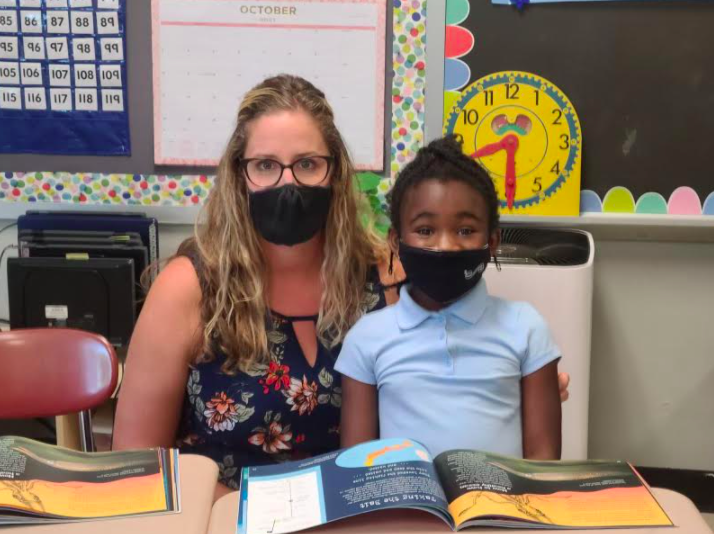

Beyond each district’s own staff requirements and various program machinations are children like 8-year-old Nonso Anaedozie of Baltimore who loves math so much she practices multiplication on the weekend just for fun.

The third-grader spends most of her school day learning alongside other advanced students: Their coursework is, on average, six months to a year ahead of their typical peers, one of her teachers said.

Nonso, whose father hails from Nigeria, is also pulled out of the classroom for advanced work in mathematics and English language arts.

Teachers describe the little girl as highly verbal, creative and confident — she won’t just write a song but sing it in front of the class, they say.

Nonso hopes to one day become a dancer and artist — she was particularly happy with her sculpture of donuts and coffee in addition to her rendering of Van Gogh’s The Starry Night — but is also considering a career in “peacemaking,” a skill she’s been honing since she was a young child.

“In kindergarten, I helped kids who were sad,” Nonso said. “And now, I help people become friends, which solves their problems.”

The child was identified as advanced just before she started kindergarten based on her performance on a gifted education admissions test. She said the advanced coursework makes her appreciate all of her special gifts and that she enjoys the challenge of her tougher curriculum.

“It helps me think about my talents and makes me think about being myself — different from others — which I really like,” she said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)