Poll Shows Not All Students & Teachers Are Eager to Go Back to In-Person School

Arnett: Education leaders must accommodate the views of those who break from the majority if they are to truly serve their communities' varied needs

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

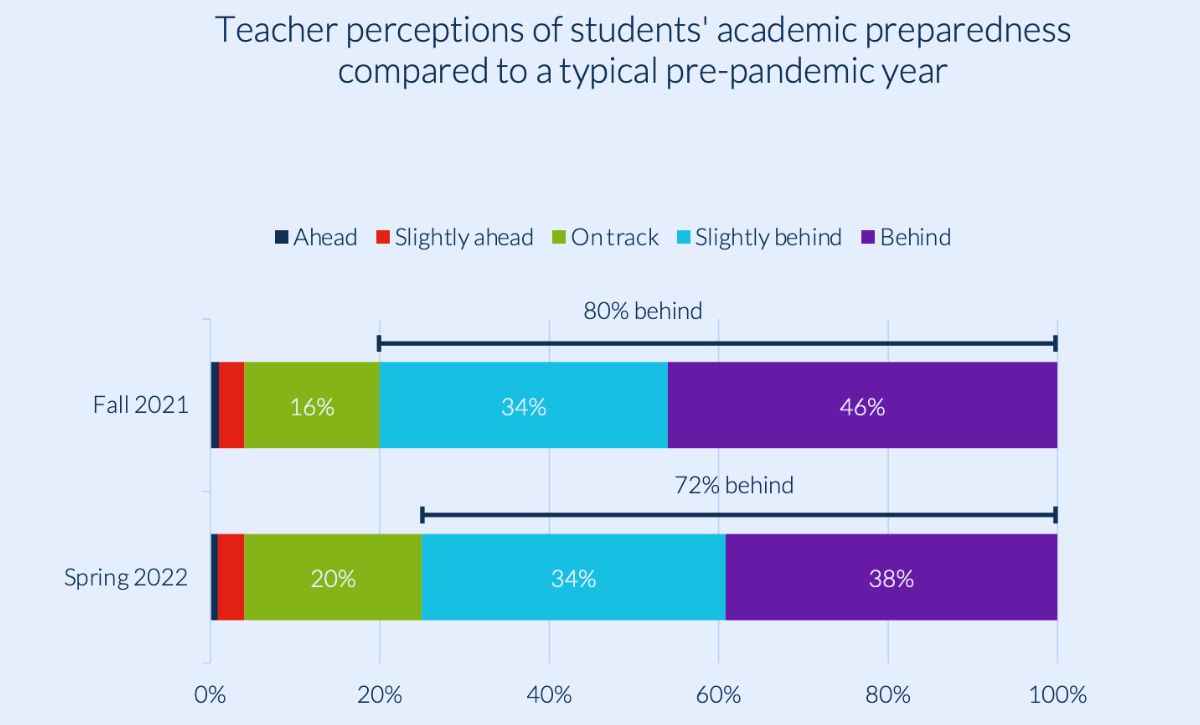

As the 2021-22 school year came to a close, schools in many parts of the country seemed to have finally reached some semblance of pre-pandemic normalcy. But new data reveals a disconnect between the learning schools offered and the views of many teachers and students on what would be best for them.

According to an April survey conducted by the Christensen Institute and Bay View Analytics, 97% of teachers reported they were teaching in-person last spring, yet only 85% said they preferred in-person instruction — a 12-point difference. Similarly, a recent Pew Research survey conducted in April and May found that 80% of teens were attending school completely in person, while only 65% said they preferred completely in-person instruction — a 15-point gap.

The majority preference for in-person instruction fits with the common research-based narrative that hastily implemented remote and hybrid instruction harmed students’ academic growth. But generalized conclusions also marginalize the perspectives of the small but notable minority who indicate that in-person instruction is not what they prefer. If education leaders and policymakers want to do right by all students and teachers, they need to take a more nuanced view on remote and hybrid teaching by considering why some might favor these approaches.

While survey data do not delve into why teachers and students hold their stated preferences, it’s worthwhile to consider a few research-based hypotheses that might explain their views.

Academics

Despite the generally negative effects of school closures on learning, remote and hybrid arrangements during the height of school building closures were not monolithic experiences. They looked different from school to school and from classroom to classroom, and some found ways to make hybrid instruction work well. For example, some teachers created videos that allowed students to receive instruction on their own schedule and used class time to focus more on providing individualized support. There is no good research on whether more innovative approaches to remote and hybrid instruction can produce better academic outcomes than conventional in-person instruction, but innovative approaches should be explored and evaluated before they’re shut down.

Unique learning needs

For some students, in-person school presents challenges. Children who have experienced bullying or have learning differences such as ADHD or autism may find that remote or hybrid arrangements work better than in-person class because they take away in-school factors that hamper their learning. Other students may simply prefer remote learning because it distances them from negative influences at school that detract from their learning — like pressure to fit in with the dominant peer culture. Where these types of student needs exist, they should not be ignored.

Flexibility to accommodate other priorities

Some families took advantage of remote instruction to travel together, unconstrained by the geographic constraints imposed by in-person instruction. Additionally, as the Pew survey revealed, many teens came to feel closer to their families over the course of the pandemic, likely due to the increased time they had together while they weren’t spending their days in school buildings.

Challenges associated with poverty

According to our latest survey, 38% of low-income students said they prefer remote and hybrid instruction, as did 17% of teachers who work in high-poverty schools. What might explain these differences? Low-income students often face transportation issues, housing insecurity and other challenges that make it difficult to show up to school on time and ready to learn on a daily basis. Low-income students may also have heightened concerns about COVID-19 exposure because of a lack of access to health care, greater likelihood of living with medically vulnerable family members or greater risk of lost family employment and income due to contracting the coronavirus. For these students, remote and hybrid instruction may be less than optimal, but they are far better than missing school.

Affirming racial identity

Our survey also indicated that remote and hybrid options were preferred more often by Black students (41%) and by teachers who serve mostly non-white students (23%). For children who experience racism and discrimination at school, learning in remote or hybrid arrangements might provide a needed escape from oppression. And even if that is not the case, some Black students may prefer remote and hybrid options because they can provide a racially and culturally affirming setting.

Teacher burnout

Educators have experienced overwhelming stress this year. As a result, some teachers may prefer remote or hybrid instruction not because they are superior modes of instruction, but because they can make the workload more manageable. As schools face teacher shortages, remote and hybrid teaching options may be an effective way to retain staff who might otherwise leave the profession.

School systems face a mountain of challenges right now, and working through them all isn’t easy. There are no silver bullet solutions — all decisions involve tradeoffs. As schools are once again able to open their doors, full-time, in-person instruction may well be the best option for most students and teachers. But it’s also important for education leaders to consider and accommodate the views of those who break from the majority if they are truly interested in serving their communities’ varied and diverse needs.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)