How Partisan Flips Could Reshape Education Battles Underway in Kentucky, Nevada, Missouri

Seven states have new governors, four from the opposite party of their predecessor, and legislative chambers in five states have swapped party control. Each of those policymakers will have an impact on state education budgets and new regulations and plans issued under the Every Student Succeeds Act. Much of that activity will be in the first part of 2017, since many legislatures meet only for a few months a year, and several only in odd-numbered years.

In three states — Kentucky, Nevada and Missouri — flips in party control of statehouses and governor’s mansions could have big effects on specific, often contentious education policies.

Voters in the Bluegrass State for the first time in 95 years gave Republicans control of the state House. That change could be a key step to passing a charter school law in Kentucky, one of about a half-dozen states still without one on the books.

“I think it’s the best opportunity that we’ve ever seen in the state to pass a strong charter school law,” said Todd Ziebarth, senior vice president for state advocacy and support at the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools.

Republican Gov. Matt Bevin, elected in 2015, is also a supporter of charters.

Previous attempts had failed in the state House when they were blocked by Democrats, who opposed the schools that are publicly funded but independently run. A bill last year to create a pilot program passed in the state Senate, where three Democrats also supported it. The House never considered it.

Sen. Gerald Neal, Democratic caucus chair, pre-filed a similar bill December 9 that would create a five-year pilot program to allow school boards in Louisville and Lexington to authorize up to two charter schools per year, starting in 2018–19.

Despite the universal GOP control, a charter law is not a done deal in Kentucky, Ziebarth said. “Even though Republicans control both chambers now, we’ve seen challenges from within that caucus in some of these other states,” he said, citing recent fights in Maine, Mississippi and Alabama.

He expected battles about authorizers (there should be at least two, he said), the geographical limitations on where schools can open, and funding.

(The 74 Flashcards: 13 Things to Know About Charter Schools)

“Those are sort of the main things that the state needs to address, and I think it’s easier said than done,” Ziebarth said. “There’s typically challenges and battles around each of those parameters, even in a red state like Kentucky is now.”

The Kentucky legislature reconvenes January 3 and will be in session until March 30.

Nevada made national headlines in 2015 when lawmakers passed the first universal education savings account program in the country. Students across the state could use, on average, $5,100, in state funding for private school, tutoring or other education options.

(The 74: Desperate Times Call for Urgent School Reform in Nevada)

It was challenged in court almost immediately, with the ACLU and others arguing that the program violated a prohibition in the state constitution on state support of religious education as well as a requirement that states fund a “universal system” of public education.

The Nevada Supreme Court in September ruled that the basic premise of the program was constitutional but that lawmakers had to come up with another way to fund it, outside of the regular state school funding stream.

(The 74: Desperate Nevada Parents Hope Court Upholds Education Savings Accounts)

The Republican majority that passed the ESA program is no more. After the November 8 elections, Democrats will control both houses of the Nevada legislature, and there seems to be little support among that caucus to find a new funding mechanism.

“ESAs are not high on the priority lists for Democrats,” Senate Majority Leader Aaron Ford told a local news station. Instead, Democrats will focus on closing a budget deficit and implementing a new, and costly, weighted student funding formula.

When pressed on whether that meant the new majority absolutely would not consider an ESA fix, Ford said, “We have no intention of passing ESAs.”

That doesn’t mean all the usual opponents are totally opposed to a funding remedy.

John Vellardita, president of the Clark County Education Association, told the Las Vegas Review-Journal his group wouldn’t oppose a fix to the ESAs, so long as they’re funded outside the regular schools budget and are means-tested, and the state legislature fully funds the weighted school funding formula.

Gov. Brian Sandoval, a Republican, has said he’ll ask for separate funding in his next budget request, though he didn’t specify exactly from where the money will come. Nor did he address whether he will ask for a cap on the program. Sen. Scott Hammond, sponsor of the original ESA bill, said a cap was required for budgeting purposes if the program is funded through some mechanism other than the regular education budget, according to the Las Vegas Sun.

In the meantime, the state treasurer’s office is still accepting applications, which are being put on hold until funding is provided. Some 8,000 families have already applied.

“The program is really ready to start working as soon as they get funded,” said Valeria Gurr, director of communications for the Nevada School Choice Partnership. “Families are not going to just let this program go.”

The Nevada legislature will be in session February 6 to June 5.

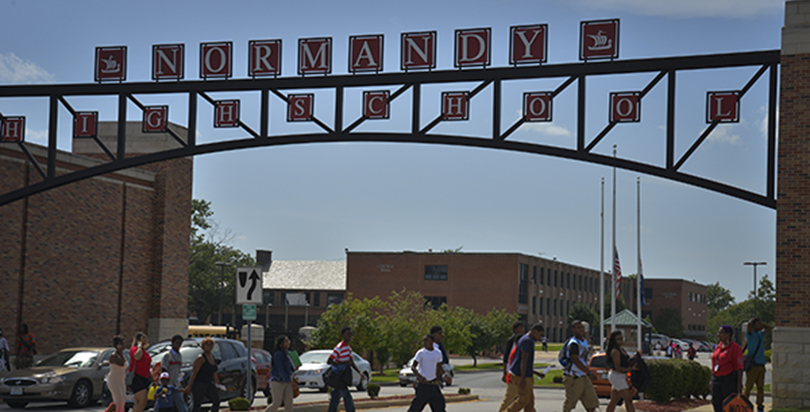

Missouri since 1993 has allowed students enrolled in districts so low-performing that they lost their state accreditation to transfer to other districts at their home district’s expense. Among the unaccredited districts was Normandy, the home of Michael Brown, the black teenager whose death at the hands of police set off nationwide protests.

(The 74: A Year After Ferguson, St. Louis Parents Fight to Escape Michael Brown’s Terrible High School)

The provisions proved incredibly costly for unaccredited districts, and the receiving districts were often less than welcoming to the low-income students of color who transferred.

The GOP-controlled legislature in 2015 passed a bill that would have modified the transfer law so that each individual school would have to be accredited, requiring students in failing schools to transfer somewhere within their own district first. If there wasn’t enough room in any of those schools, they could then transfer to outside districts or consider other options, including charters and virtual schools.

The bill also expanded charter schools from just the cities of St. Louis and Kansas City into parts of the neighboring counties.

Gov. Jay Nixon, a Democrat, vetoed it, saying in a message to the state legislature that it “mandated expensive educational experiments, neglected accountability and evaded the major, underlying difficulties in the transfer law.”

Nixon had vetoed another version in 2014 that would have allowed students in unaccredited districts to transfer to private schools.

But now Nixon, unable to seek re-election because of term limits, will be replaced by Republican Eric Grietens, who said on the campaign trail he’s willing to consider broader choice options.

“I think Missouri is definitely positioned for some student-centered education policy change,” said Peter Franzen, associate executive director of the Children’s Education Alliance of Missouri.

That said, education reform in Missouri, as elsewhere, isn’t a neatly partisan issue, and some Republicans didn’t back previous overhaul efforts. It often comes down to the districts lawmakers represent, Franzen said.

“It’s never a given. We definitely see reform as a bipartisan issue, so I never think it’s as simple as identifying the Democrats and the Republicans, just because they represent vastly different parts of the state,” he added.

Missouri legislators return to session January 4 and adjourn May 12.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)