Pandemic Widened Ohio Achievement Gaps, Leaving ‘Vulnerable’ Students Further Behind

Test scores for low income, Black, Hispanic, and special education students leave them worse off than pre-COVID

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

White, affluent and suburban students escaped serious learning damage from the pandemic, but low income, Black, Hispanic and special education students fell even further behind, new Ohio test scores show.

Though test scores in 2022 improved statewide compared to those from a chaotic 2020-21 year of shuttered schools, online classes and scarce vaccines, those historically struggling groups had taken too much of a hit to catch up.

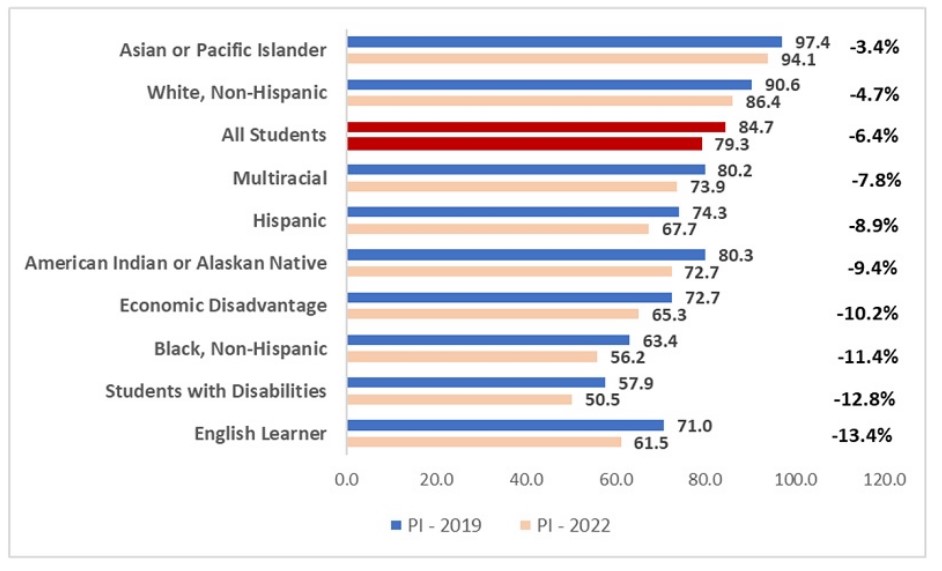

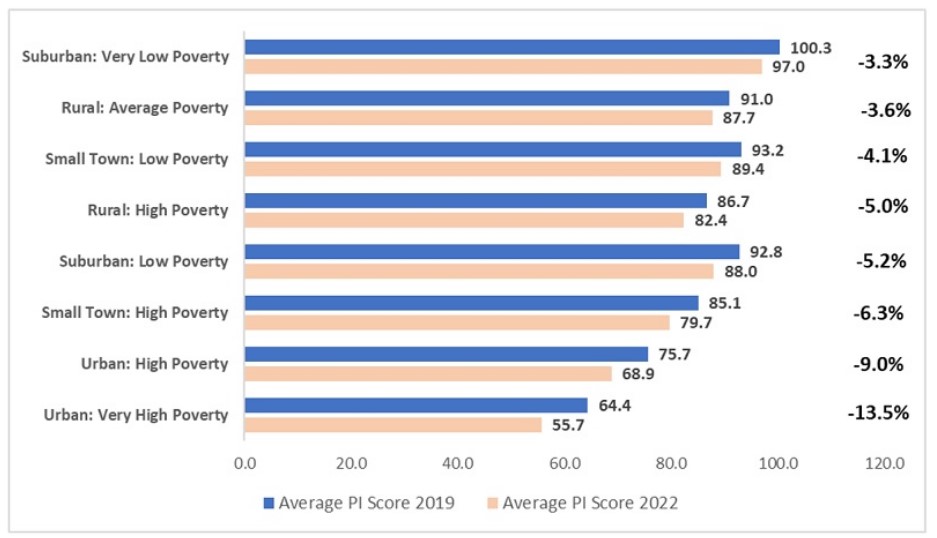

Test scores fell twice as much since 2019 for “vulnerable” students than their white peers, one analysis shows. That meant urban, high poverty schools districts had four times the score decline as affluent suburban ones.

“We saw improvement across the board. That’s the good news,” said Chris Woolard, Chief Program Director of the Ohio Department of Education, adding a “sobering” caution: “The vulnerable students are the most impacted. We had achievement gaps before the pandemic. The achievement gaps are worse.”

Ohio’s annual report cards for schools and districts released last month mirror many of the findings of the National Assessment of Education Progress (NAEP) this month that student reading skills had their biggest drop in 30 years and that math scores, after years of incremental increases, fell for the first time.

Scores from Ohio, with the sixth-most students of any state, offer more detail than NAEP and other large states are currently providing. The NAEP data released so far only covers nine-year-old students. NAEP scores for individual states and cities won’t be out until late October. And while large states like California and New York are allowing individual districts to release scores if they want, they are not releasing statewide data to offer any comparisons.

In Ohio, gaps were also apparent between younger students and those in high school; and between math scores and English scores.

The greatest recovery came in English in early grades, while math scores lagged and some high school students made little recovery, or even regressed, an analysis by Ohio State University Vladimir Kogan found.

The net effect, Kogan said, is that students remain a third of a year to a half year behind in English, but full recovery could come soon.

“If the pace of recovery observed between the 2021 and 2022 school years can be sustained, ELA achievement could return to pre-pandemic levels within the next two to three years in most grades,” he wrote in his analysis.

But the drop in math is between a half year and a year’s worth of learning, which will take longer to recover.

“The students learned more (in English) last year than students prior to the pandemic, particularly in the younger grades, but we don’t see really any acceleration in math in any of the grades,” Kogan said.

Michael Casserly, former executive director of the Council of the Great City Schools, a national association of big city districts, called the results out of Ohio and other states “actually pretty encouraging.”

“It’s just preliminary, but it looks like a combination of just getting kids back in the classroom, the summer school, the emphasis on staying on grade level in the regular classroom instruction is starting to move the needle,” Casserly said.

The good news:

- Ohio’s test scores crashed between spring 2019 and spring of 2021, but students made up more than half of that loss by 2022, regaining 5.6 points of a dramatic 10 percent drop. That comeback is “just sort of unheard of,” Woolard said, because state scores typically change just a point or two from year to year.

- Test scores for many districts have almost fully recovered or even surpassed previous scores, according to former state representative Steve Dyer, a Democrat who has remained active in state education debates. Dyer noted in his blog 43 out of Ohio’s 607 districts scored higher in 2022 than before the pandemic and 55 percent of districts are within five percent of their 2019 scores.

“Amid all the recent doom and gloom reporting about our children falling behind because of COVID, Ohio’s public schools have done a remarkable job recovering significant amounts of those losses,” Dyer wrote.

The bad news:

- Ohio’s overall test scores are the lowest since 2014-15 wiping out the small gains districts have made since then.

- State proficiency rates — students with strong scores — show students faring far worse in math in 2022 than English. Statewide, the drop in proficiency was double in math, about 10 percentage points, than the five point drop in English.

- Test scores fell much more for “vulnerable” groups than for white and Asian students or the state overall. A calculation by the right-leaning Fordham Institute, found while scores for white students fell less than five percent since 2019, it fell nine percent for Hispanic, 10.2 percent for low income, and even more for Black students and for English Learners and students with disabilities.

- Ohio’s large urban school districts, which face greater socioeconomic challenges than the rest of the state, saw test scores fall harder between 2019 and 2022, even after significant recovery over last school year. All districts in the Ohio 8, a coalition of eight urban districts, had bigger drops than the state’s overall drop of 5.4 points in Performance Index, the state’s composite of all test scores over all grades.

Some urban districts, like Canton and Cincinnati, had double the statewide drop. Others, like Cleveland and Dayton, have fallen only a little further behind.

“The pandemic hit us hard,” Cleveland schools CEO Eric Gordon said. “But community surveys show clearly that the community expected this. Polls show also that our families remain confident that [the district] can and will get our kids and district back on an upward trend. And we have – outpacing many districts.”

- As expected, more affluent and suburban districts had much lower declines than poor and more urban ones. As Fordham’s Aaron Churchill calculated, urban and high poverty districts saw scores decline 13.3 percent – four times as much as the 3.3 percent for suburban districts with very low poverty.

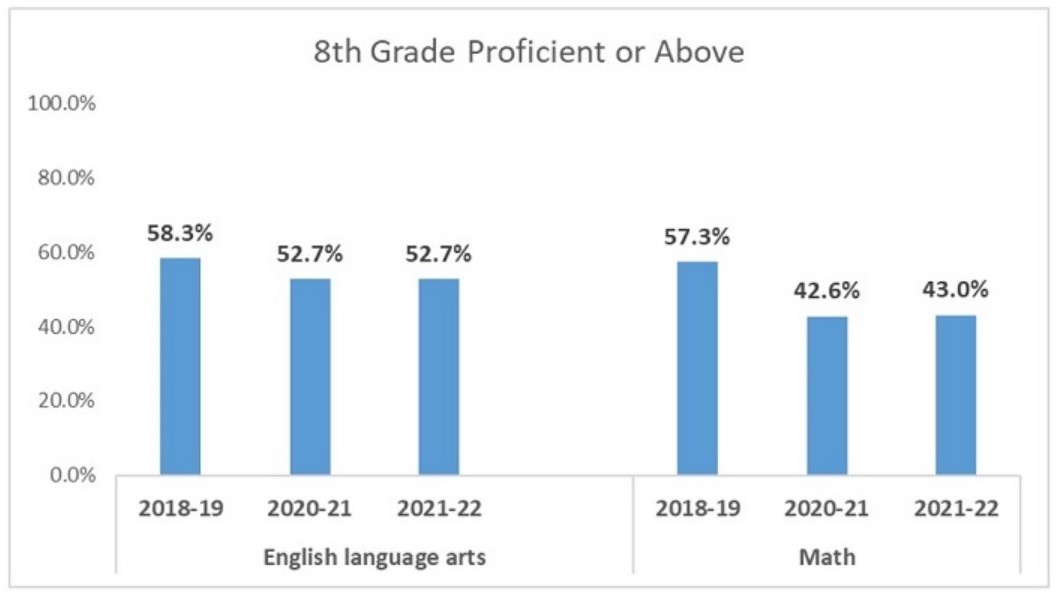

- Older students in 8th grade and high school are not recovering well.

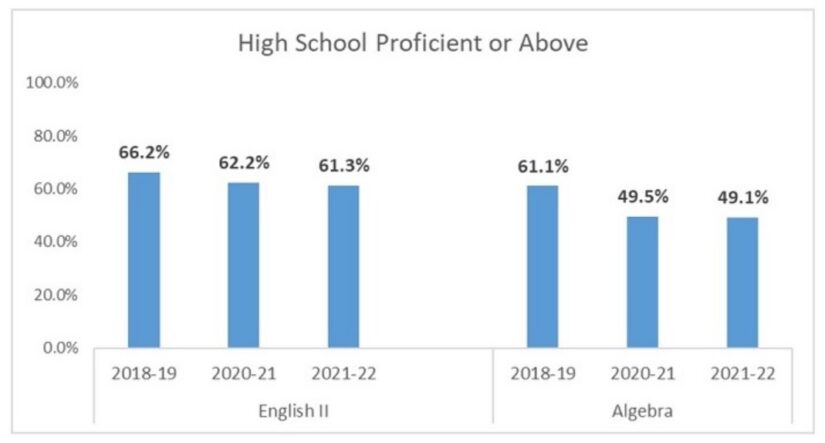

As Churchill pointed out, proficiency rates for eighth grade math and English barely improved in 2022, if at all. For high school algebra and English II exams, proficiency rates dropped slightly.

“Ohio cannot afford to leave tens of thousands of students lacking the basic literacy and numeracy skills needed to succeed in life,” said Churchill. “State leaders need to set a faster pace for learning recovery—especially in mathematics—by restoring a focus on core academics and ensuring that schools are using highly effective practices.”

Kogan’s research found a similar pattern with older students not making up lost ground..

“Their scores are worse,” Kogan said. “So they have not caught up and in fact, if anything, they seem to have fallen further behind.”

“(That’s) obviously very concerning because we don’t have much time left for these high school students,” he said. “So obviously, that should raise the urgency of really targeting interventions to these older students.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)