74 Analysis Shows Girls Already Outperform Boys at NYC’s Elite Schools Amid Fear That Opening Up Admissions Would Water Down Quality

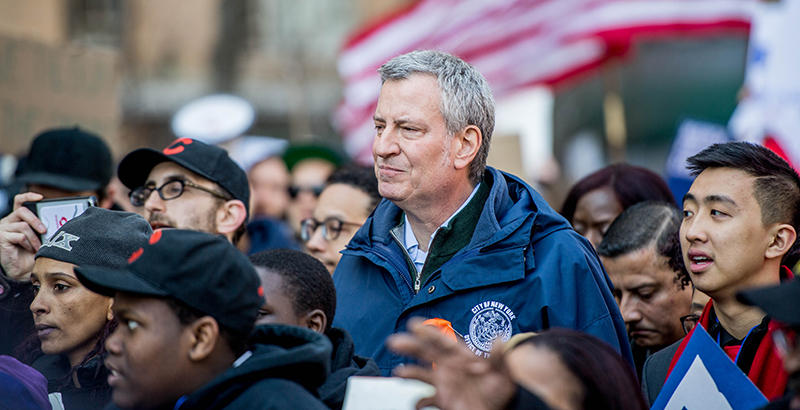

The battle was joined. Mayor Bill de Blasio’s plan to diversify New York City’s specialized schools was met by vehement protest from alumni and Asian groups determined to block the dismantling of an admissions system they believe ensures the schools’ academic excellence.

But the mayor went silent on the proposal almost immediately after he announced it on June 3, and the speaker of the state Assembly, which needs to vote on the controversial change, said last week it wouldn’t act until after the next session starts in January. Even in that chamber, which is dominated by Democrats, passage is far from certain; the odds are steeper still in the state’s divided Senate.

It’s as if a difficult reckoning about race, class, and merit in city schools — put on hold 47 years ago when state legislators passed a law requiring use of a single “objective” test for admission to these mostly math- and science-focused schools — was unpaused, then paused again.

Then, as now, advocates argued that a system like the one de Blasio has proposed, in which the top 7 percent of academic performers from every middle school will be offered spots, is sure to result in many students arriving ill-equipped and likely to struggle while better-suited students are shut out.

“If we allow people that aren’t prepared, we’re setting them up for failure, they won’t be able to keep up with the rigor of the program, and that’s the bottom line,” a parent leader told the Staten Island Advance.

Perhaps, but the mayor’s initiative would also give more offers to a particular kind of student — one more likely to earn high GPAs, achieve college readiness on Regents exams, and graduate with top honors.

That type of student is girls.

According to the city’s calculation, girls would receive 62 percent of offers under the new policy — a big leap. Over the past three years, girls received 45 percent of offers; they constitute just 42 percent of the more than 15,000 students enrolled in the eight elite schools, a proportion that has remained essentially unchanged for years.

Although more girls than boys sit for the test, girls are less likely to get an offer and more likely to turn one down.

An analysis of Regents test results and high school graduation data by The 74, however, shows that girls who do enroll in the specialized schools outperform boys — not always by a large difference, but repeatedly across time and at each of the tech-focused schools.

“Fewer girls get in, and girls do better,” said Lazar Treschan, director of youth policy at the Community Service Society, which has advocated for admissions reform in the specialized schools. “That’s a good analysis. That alone should be a huge red flag that we’re not heading in the right direction.”

Mean scores on Regents exams at specialized schools, 2015-2017

Share of students at specialized schools scoring 80 or above on Regents exams, 2015-2017

Source: NYC Department of Education

Between 2015 and 2017, The 74 found, girls had higher mean scores on the annual state Regents tests in 12 of 13 different subjects. (Boys had a slightly higher average in physics, 85.1 to 84.9.) Girls were also more likely in 11 subjects to score above 80, which denotes college readiness on several of the tests.

While girls performed at high levels on the English and Global History tests, as some might expect, the Regents exams with the largest gender gaps were Common Core Geometry, with 84.5 percent of girls scoring in the top quintile, compared with 77.7 percent of boys; and chemistry, where 74.7 percent of girls were near the top, compared with 68.6 percent of boys.

The Department of Education did not respond to several requests for comment on why girls receive fewer offers yet outperform boys in specialized schools.

Despite the disproportionately small population of girls, who are 48.5 percent of all New York City public school students, concerns about fairness in specialized school admissions have long focused on race. Black and Hispanic students constitute 67 percent of city students but only 10 percent of those in specialized schools.

By contrast, Asian students are roughly 16 percent of the city’s enrollment and make up 61 percent of specialized school enrollment. White students are about 16 percent overall and 24 percent of specialized school students.

The DOE would not provide a racial breakdown of the specialized schools’ male and female students, but there’s no indication that the totals by gender would differ meaningfully. Stuyvesant High School did not admit girls until 1969, after it lost a civil rights lawsuit, and Brooklyn Technical High School didn’t go co-ed until 1972. Bronx High School of Science began accepting girls in the 1940s. The five other specialized schools founded later — High School of American Studies at Lehman College, Staten Island Technical High School, High School for Mathematics, Science and Engineering at City College, Queens High School for the Sciences at York College, and The Brooklyn Latin School, admitted girls from the beginning.

In the classroom, girls ≠ boys

The superior performance by girls on Regents tests conforms to decades of studies on gender differences in education. Studies dating back to the 1950s and 1960s find that girls get better grades. A 2008 review of research found, “Today, from kindergarten through high school and even in college, girls get better grades in all major subjects, including math and science.”

The authors reported that “twice as many boys as girls have difficulty paying attention in kindergarten, and girls more often demonstrate persistence in completing tasks and an eagerness to learn.” A 2006 study co-written by Angela Duckworth, of “grit” fame, found that girls excel because they have more self-discipline than boys.

“Girls tend to study to understand the material,” says Marisa Schwartz, a veteran New York City high school English teacher and specialized test tutor who has a son at Stuyvesant. “Whereas boys study in a different way. They’re studying to focus on improving their grade. It’s more performative. Generally, students who study to understand the material will get much better grades.”

Capturing these sorts of non-cognitive assets in a standardized test seems challenging. Although data are scarce, a 2015 CUNY dissertation measured the specialized test for validity — whether it is fair to different types of students. The study results were narrow — it looked only at how well the test predicted freshman GPA — but it found gender bias: “Girls earn higher grades than boys with equal SHSAT (Specialized High School Admissions Test) scores. This finding holds true across all ethnic groups,” wrote the author, Jonathan James Taylor.

“If the purpose of the SHSAT is to admit a class with the greatest chance of success at school, it is apparent that the same metric cannot be used for boys and girls,” he said.

Aaron Pallas, a professor of sociology and education at Columbia University’s Teachers College and part of the committee that oversaw Taylor’s thesis, said measuring for bias was difficult because the DOE isn’t clear about the test’s purpose.

The student handbook includes extensive prep exercises and says “the test measures knowledge and skills students have gained over the course of their education.” The description in state education law is also generic and perhaps outdated: Admission “shall be solely and exclusively by taking a competitive, objective and scholastic achievement examination.”

“Beyond its role as the sole criterion for admission to the eight exam schools, is it supposed to predict who will do well in high school, and an exam school in particular? ” Pallas said in an email. “Is it supposed to predict who will graduate and go on to a selective four-year college? The murkiness about what the test is ‘supposed’ to measure compromises our ability to assess whether it predicts what it is supposed to, and whether it does so as well for girls as for boys.”

By any of those criteria, girls in specialized schools do better than boys, though Pallas said test bias isn’t necessarily the reason.

Taylor also suggested that the exam’s format, which is nearly all multiple choice, might have contributed to lower scores for girls. Research shows that boys do better on multiple choice while girls are stronger on questions that ask for a written response.

Harvard University Graduate School of Education professor Dan Koretz, a testing expert, said there’s a limit to what even the best single test can do. “Even if the test were functioning perfectly, I’d be surprised if it accounted for more than a quarter of the difference in performance” between boys and girls in high school.

“Assuming it’s a perfect test for its purpose, we’re going to find that it accounts for only a modest share,” Koretz said.

Getting information about the test has never been easy. “They’re very secretive,” Koretz said, recounting that the company that produced the test, which is now owned by Pearson, once refused to give him technical materials. Koretz called it “a violation of explicit professional standards.”

Despite several requests, the DOE did not provide a technical manual, which explains how questions are created and reports on the test’s potential bias.

A model for a similar plan to the one the mayor has proposed does show that incoming students’ average English and math scores at the specialized schools would be lower if the test were eliminated. The city says student scores and grades would be about the same, based on a model of the top 7 percent of eighth-grade students this year.

Graduation rates at specialized schools, 2005-2013

Students who graduated by August following four years in high school (Source: NYC Department of Education)

Gender gap in graduation

The specialized school gender gap is also evident in graduation data. Once more, the differences are remarkably consistent if not always large. Using figures for students who completed their studies by August following their senior year, girls in specialized schools graduated and earned Advanced Regents diplomas (which require passing additional exams) at higher rates than boys in every year between 2005 and 2013, the latest year for which data are available.

This held true in every specialized school except the High School for Math, Science, and Engineering, where girls trailed by one-tenth of a point over that time. Cumulatively, 94.1 percent of girls earned Advanced Regents diplomas, compared with 89.5 percent of boys.

Girls were also less likely to graduate with a local diploma, which was phased out because it was insufficiently rigorous, less likely to remain in school after four years, and less likely to drop out across the eight elite schools, though the differences were small.

As the city moves forward by turning back to re-evaluate a test-only admissions policy implemented little more than a year after girls first enrolled in Stuyvesant — an era when the city designated Asians as “Orientals” and Hispanics as either “Puerto Ricans” or “Other Spanish Surnamed” — the strong performance of female students has been a constant.

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

;)