Analysis: New Review of Online Educational Materials Finds They’re Not Up to Snuff, but Teachers Like Them. We Need a Rotten Tomatoes for Curriculum

Lately, those of us in education have been asking lots of questions about curriculum, like what curricula are schools using and are they high-quality? Yet those simple questions are difficult to answer when we know that teachers in the real world are finding some of their instructional materials on the internet.

In fact, the vast majority of teachers either are supplementing their core curriculum or don’t have a core curriculum to start with. So it’s no surprise that they often frequent the online marketplace to meet their instructional needs. Recent studies by RAND found that nearly all teachers report using the internet to source instructional materials, and many do so quite often. For example, 55 percent of English language arts teachers said they used Teachers Pay Teachers for curriculum materials at least once a week. That site reports that 1 billion resources have been downloaded — a massive number, to be sure.

Yet we know almost nothing about the quality of such supplementary materials. Although several organizations have stepped up to offer impartial reviews of full curriculum products, to our knowledge, there’s no equivalent when it comes to add-on resources.

A new report out this week from the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, The Supplemental Curriculum Bazaar: Is What’s Online Any Good?, provides one of the first analyses of whether popular websites are supplying teachers with high-quality supplemental materials. The University of Southern California’s Morgan Polikoff conducted the study, along with educational consultant and lead reviewer Jennifer Dean. Dean was joined by four other expert reviewers with backgrounds in teaching English language arts, developing curricula and assessment items, and/or leading instructional departments.

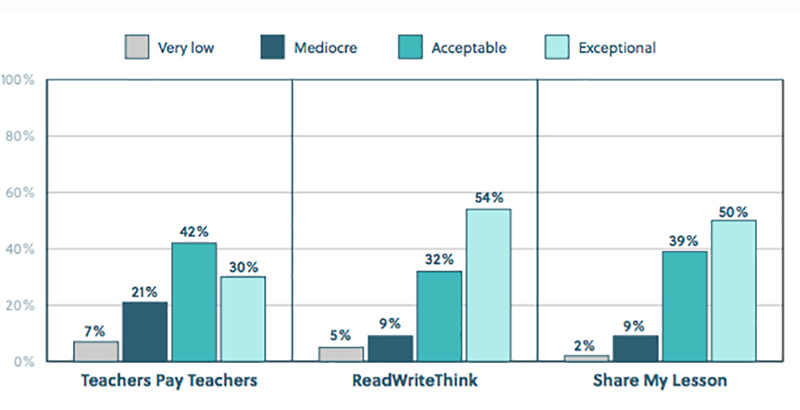

In all, they examined more than 300 of the most frequently downloaded materials found on three of the most popular supplemental websites: Teachers Pay Teachers, ReadWriteThink and Share My Lesson.

They unearthed a wealth of valuable information that has important implications for instructional leaders everywhere, as well as for classroom teachers themselves. Unfortunately, the headline is that their reviews concluded that the majority of these materials were not up to classroom snuff. More precisely, 64 percent of materials, according to their scale, should “not be used” or are “probably not worth using.” On all three websites, a majority of materials were rated 0 or 1 on an overall 0-3 quality scale. In addition, most materials did not fully align to the state standards to which they claimed to be aligned; student assessments did a poor job covering core content; and the vast majority of tasks were focused on lower-level skills.

That’s sobering, to say the least, particularly given the popularity of these sites and the materials reviewed. It suggests a major mismatch between what the experts think teachers should (and shouldn’t) use in classrooms and what teachers themselves are downloading for such use — and, in some cases, paying for.

That’s not necessarily a criticism of the teachers. They may find value in these materials in ways that we “experts” need to better understand. In interviews, teachers said they use the materials to fill instructional gaps, meet the needs of both low and high achievers, foster student engagement and save them time. They rarely use the materials as is. Much adaptation goes on as they choose and modify items to fill specific needs— needs that likely take precedence day to day over whether particular materials are aligned to state standards or incorporate high cognitive demand (or some other quality valued by experts).

We’re not suggesting that teachers’ views and judgments should yield to those of experts. Why not weigh both? Consider how this works on Rotten Tomatoes, the popular website that reviews the quality of movies and other entertainment. Its Tomatometer is based on the opinions of hundreds of film and television critics and is a trusted go-to for millions of viewers. When at least 60 percent of the critics’ reviews of a movie or TV show are positive, it receives a red tomato, meaning it’s “fresh.” Less than 60 percent, and it gets a green splat, meaning it’s “rotten.”

Those could reasonably be termed expert judgments. But the Rotten Tomatoes site also provides Audience Scores, which are just that. When at least 60 percent of viewers give a movie or TV show a star rating of 3.5 or higher, a full popcorn bucket indicates that it’s “fresh” from the audience’s perspective. When less than 60 percent do, a tipped-over popcorn bucket reveals it’s “rotten.”

So the moviegoer and television watcher can readily access two distinct ratings — one from professional critics and another from the audience. Often they’re similar, but not infrequently, they diverge. It’s hard to say who is right, but potential viewers get more information by seeing both ratings than they would from just one.

Same thing here. In a majority of cases, materials with high “Audience Scores” — those that had been downloaded the most — got a green splat from our expert critics, even though teachers rewarded them with a full popcorn bucket.

What then? Should we search for ways to block or deter teachers from using materials that experts don’t like? We certainly understand that impulse, but heavy-handed approaches have a way of backfiring.

We think a better solution is simply to provide teachers with more information, Tomatometer-style. In addition to providing user reviews or comments to teachers, or highlighting and promoting the most popular lessons, the platforms should also make expert reviews available. Let teachers see multiple opinions and weigh the pros and cons for their particular students.

Beyond that, instructional leaders should pay a tad more attention to what’s actually taught in classrooms by way of supplemental materials — no matter their quality. That’s because curricular coherence — the way in which curriculum is purposefully sequenced to build meaning — is often the first casualty of online trawling.

If supplemental providers and schools do those two things, maybe, just maybe, we can help shore up the gaps in a core curriculum instead of sabotaging it. And turn out a most delicious tomato sauce!

Amber M. Northern is senior vice president for research of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute. Michael J. Petrilli is president of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)