What if College Admissions Relied on Random Lotteries? Fewer Black, Low-Income, and Male Students Would be Accepted, New Study Finds

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Going back over 50 years, public intellectuals have toyed with a radical idea: What if colleges used random lotteries to admit students?

It’s a notion that first caught on in the 1960s, when middle class families sought more access to higher education and the paths to prestigious schools became increasingly competitive. Since then, lotteries have been touted as a possible solution when the admissions process has come under scrutiny — most recently, after the “Varsity Blues” bribery scandal and a federal lawsuit alleging that Harvard discriminates against Asian-American students.

But new research suggests that switching to a lottery-based system could create significant new challenges for schools looking to promote racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic diversity. The study, published today in the journal of the American Educational Research Association, finds that low-income, Hispanic, and African American students would be less likely to gain acceptance to colleges in a multitude of lottery scenarios; in some cases, even the percentage of male students admitted would be sharply reduced.

Dominique Baker, a co-author of the study and a professor of education policy at Southern Methodist University, said she was drawn to study the question because of the wide range of advocates on different sides of the American political spectrum who have supported randomizing college admissions for a variety of reasons.

A former assistant dean of admissions at the University of Virginia, Baker noted that lotteries are too often perceived as a silver bullet for what ails higher education. The mechanisms of college admissions “have an incredible amount of randomness already,” she said. “We just don’t see it because it’s an opaque process.”

Baker and her coauthor, University of Michigan professor Michael Bastedo, relied on two sets of data from the U.S. Department of Education to simulate what college admissions figures would look like under various lottery configurations. One, the Educational Longitudinal Study, followed a set of high school sophomores for several years beginning in 2002; the other, the High School Longitudinal Study, followed a different group of high school freshmen beginning in 2009. Both data sets included academic and demographic information — including grade point average as well as test scores — for large samples of students as they made their way from high school to college.

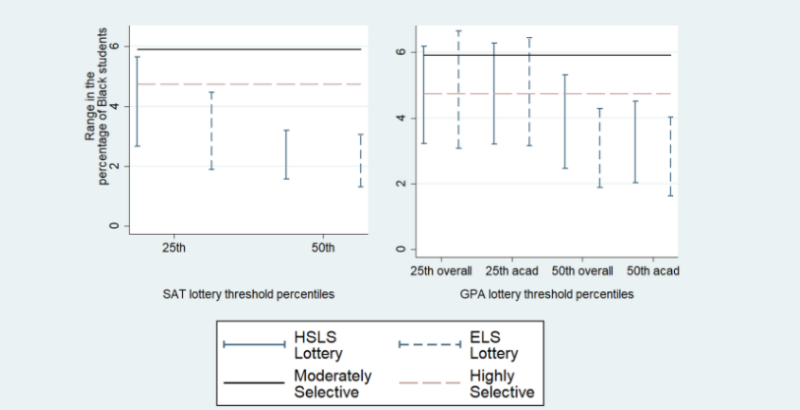

They then identified all students in each sample who fell above several minimum thresholds of academic performance: those at or above the 25th and 50th percentiles for SAT scores, GPA, and weighted GPA. These, they reasoned, would be the students eligible to participate in a theoretical national admissions lottery.

Next they generated 1,000 random simulations to project which students in the sample might be accepted to colleges that are at least moderately selective, using minimum eligibility thresholds of GPA, SAT scores, and a combination of the two. Finally, they compared those results to the sample of students who attend highly or moderately selective institutions under the current system.

Their findings were stark. Black, Hispanic, and low-income applicants generally declined as proportions of admitted students under most lottery scenarios. Consistently, lotteries that established a minimum GPA threshold for eligibility resulted in significantly lower numbers of male students being accepted than currently prevail — typically between 36 and 40 percent. When lotteries used a combined threshold consisting of both SAT scores and weighted GPA, the eligible pool of African American and Latino students fell below the proportions that are currently enrolled in selective colleges.

Baker said that the patterns seen across lottery simulations pointed to large disparities in how students from different demographic groups performed in the various eligibility measures. Black and Latino students tend to score lower than white and Asian American students on college admissions exams like the ACT and SAT, while girls generally earn higher grade point averages than boys.

“None of the thresholds that we looked at showed evidence of creating a more equitable class,” Baker said. “And you can see differences because different inequities are baked into GPA versus test scores — that’s why you see the difference for men with GPA that you don’t see for test scores.”

In terms of racial groups, virtually every lottery formation yielded higher percentages of white and Asian American students than under current admissions procedures. In some lotteries, the proportions of low-income students and students of color shrinks below 2 percent of the admitted class. This is attributable in part to the random swings in selection that go along with annual lotteries; over enough years and draws, the characteristics of admitted students would be expected to resemble those of the total pool of eligible participants. But that might not be the case in any given year, Baker observed.

“Many years’ worth of admitted classes of lotteries — 50 years, 100 years — would look kind of similar to the larger population,” she said. “But an individual lottery has no guarantee of being demographically similar to the larger population.”

It should be noted that proponents have cited many reasons why a switch to lotteries would be superior to the current system, many (alleviating pressure on prospective applicants, or eliminating the low-grade corruption of admissions officers exchanging donations for acceptance letters) unrelated to equity concerns. For those who complain that elite colleges have quietly capped the Asian American portions of their student bodies, the increased numbers of such students admitted under the study’s lottery projections could even serve as an endorsement.

Baker said that she and Bastedo were “shocked at the magnitude” of some of the shifts detected under the lottery simulations, but said the results generally reflected what existing evidence has shown with respect to performance disparities in both high school grades and college admissions exams.

“It’s well-rooted in the research literature we have. If you pick different types of thresholds, whatever demographic patterns we see for that measure, we should also expect to see them in the lottery.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)