New Research Shows Some 1 Million College Dropouts Returned to School in the Past Five Years and Earned Degrees

A mostly invisible army of college “dropouts” has actually been returning to college years after dropping out and completing their degrees, mostly two-year associate’s degrees.

The “Some College, No Degree” study released Wednesday by the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, a private nonprofit group that tracks college students, identifies 1 million students in just the past five years who returned to college to earn degrees. An additional 1.1 million former students who returned are still enrolled and pursuing degrees.

The report is important for several reasons. First, this is more evidence that the college completion rates among first-generation college-goers are not as grim as thought. These are students who fell off the radar as presumed dropouts — but revived.

Community college graduates, for example, are counted as successful graduates at the three-year mark after leaving high school. Successful bachelor’s degree-earners are counted at the six-year mark.

But what about the students who dropped out and returned 10 years later?

“The returning students and new completers identified in this report should be celebrated, but they have been mostly invisible until now,” said Doug Shapiro, executive director of the research center. “The graduation rates commonly used to measure college performance in the U.S. counted them as dropouts when they left and ignored them when they returned, yet their successes today represent great benefits to themselves, their states and the nation.”

The Clearinghouse is the only group in the country capable of tracking where individual students are in the college process, matching names and identifiers given to them by high schools against information given to them by college registrars.

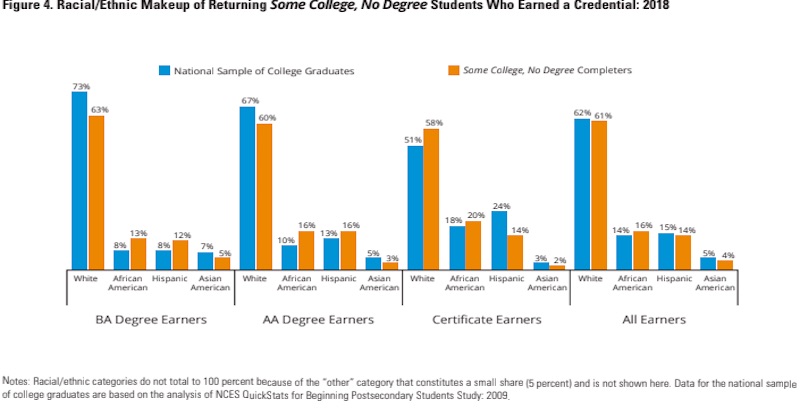

The report is also important because it points out even more ways the country can turn around its dismal record of ensuring that first-generation students, most of them low-income, minority students, not only enroll in college but earn degrees. Currently, only about 11 percent of low-income students who are the first in their family to attend college end up earning bachelor’s degrees within six years, compared with over 60 percent of students from high-income families.

Other ways to improve those college success rates were laid out in The B.A. Breakthrough: How Ending Diploma Disparities Can Change the Face of America (by this writer, published earlier this year by The 74). That book points to the improved college success rates among alumni at the major charter school networks, the proliferation of independent college advising groups offering data-driven college counseling in high-need high schools, and the beefed-up efforts at many colleges and universities to do better by first-generation students, especially by increasing community college transfers.

Finally, the report is important because it focuses more attention on the millions of students who left college without degrees. Not only are they more likely than expected to give it another try, but even those students with some college, but no degree, are an important group to pay attention to.

Earlier this year, the Thomas B. Fordham Institute released a report on non-completers, showing the economic advantages of having some college. Attending some college, even without earning a degree, boosted employment by 20 percentage points and earnings by 6 percent after 15 years.

The Clearinghouse report points out that these mostly invisible students did this turnaround with very little help from states or universities. From the report: “Imagine how far America could advance its attainment goals if states and colleges and universities, informed by the evidence from this report, actually tried to re-enroll students from the 36 million current ‘Some College, No Degree’ population, reaching out with tailored programs and policies to meet their needs.”

How can that happen? The report authors have some suggestions.

Many of these students won their degrees online, mostly because traditional college campuses are not friendly to their needs. Traditional colleges need to do more with student support services, child care, credit transfer, class scheduling and financial aid, according to the report.

The number of students who could be lured back into college is huge. Of the 36 million Americans with some college but no degree, roughly 10 percent are considered “potential completers” because they had at least two years’ worth of academic credits before they stopped out.

Once these students return, they tend to stay enrolled until they earn degrees. Typically, the completers finish within two years of re-enrolling without transferring or stopping out again.

As an example of what states can do to help more of these students, the report cites Indiana’s “You Can. Go Back” program, which drew 30 state private and public colleges into the effort and awarded 5,000 adult student grants. The partners offered more online education options and also credit for work experience and military service. As a result, Indiana has captured far more college returnees than other states.

These students need to be targeted by all states, the report urges.

“Given the projected decline in the number of high school graduates in many states, persistent equity gaps for students from low-income, first-generation and minority background, and regional attainment gaps, tapping into this population should be an essential part of a state’s strategy to accelerate and reach its attainment goal.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)