New Research: Chicago Teacher Eval Pilot Moved Out Struggling Teachers, Kept Stronger Ones

“The overall quality of the teachers in treatment schools improved as a result of the … initiative,” the study finds.

The evaluation system studied is particularly noteworthy because as secretary of education, Duncan pushed states across the country to adopt evaluation models that in some respects mirrored the Chicago pilot.

“This paper provides evidence that teacher evaluation reform … has the potential to improve the overall quality of teachers and teaching in our nation’s schools,” wrote researchers Lauren Sartain of the University of Chicago and Matthew Steinberg of the University of Pennsylvania.

The study, titled “Teachers’ Labor Market Responses to Performance Evaluation Reform,” appeared in the August edition of the peer-reviewed Journal of Human Resources.

It examined a pilot evaluation program introduced in a random set of Chicago elementary schools in the 2008–09 school year.

The randomization is key because it allowed the researchers to be confident that any differences between schools where the program was piloted and those where it wasn’t were caused by the evaluation system.

A separate study, by the same researchers, found that the program led to gains in student achievement for the first group of schools in the initiative.

The latest research looks at what happened to teacher turnover in these pilot schools. In aggregate there was no effect; that is, attrition went neither up nor down. That the program didn’t prompt an across-the-board exodus is probably a positive finding.

“Policymaker[s] and district leaders would likely be concerned if a teacher evaluation system induced turnover for the average teacher in the district, particularly in light of the aim of evaluation reform — to provide the majority of teachers with feedback to improve their practice,” the paper says.

Sartain and Steinberg then look specifically at non-tenured teachers who had received a poor evaluation rating under the previous system. Here they see a jump in teacher turnover: In the pilot schools, about 35 percent (eight out of 23) of those teachers left, compared with just 4 percent (one out of 23) of teachers in the control schools.

This is a big difference in percentage terms, but it represents a small number of actual teachers, since very few got low ratings. (Despite the small numbers, though, the results were highly statistically significant, so they weren’t likely to have been caused by chance.) This also helps explain why the net impacts on turnover were negligible even while the effects for this specific group were large.

Even more encouraging, the teachers who left were replaced by ones who were subsequently rated higher. This suggests, contrary to frequently heard concerns, that schools may be able get effective replacements for teachers they dismiss.

Notably, the study finds that tenured teachers with low ratings were no more likely to leave the classroom under the pilot system. Although they can’t be sure, the researchers chalk this up to the lengthy process necessary to dismiss a tenured teacher.

“Job protections guaranteed to tenured teachers appear to have sufficiently insulated them from the type of job displacement experienced by their non-tenured counterparts,” the researchers said.

The pilot was different from now-prevailing evaluation models in that student test scores were not considered part of teachers’ scores. Teachers were evaluated solely based on classroom observation.

Other research has also found that simply providing more information to principals on their teachers’ performance can increase turnover of less-effective teachers.

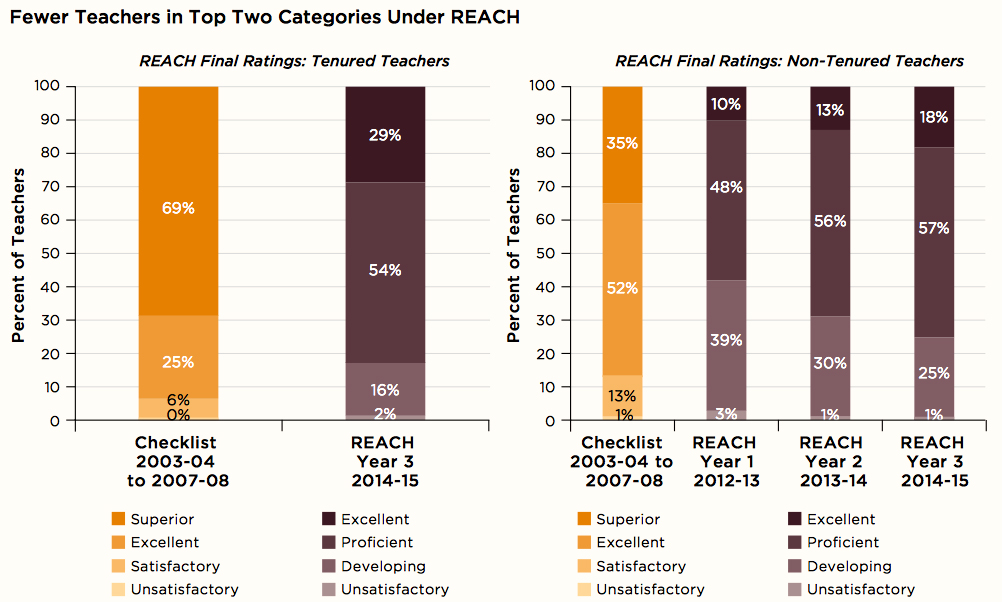

The latest study provides encouraging evidence for the teacher evaluation systems that gained traction under President Barack Obama and Duncan’s Race to the Top initiative. They have been politically controversial because they led to a large increase in student testing, and they were disappointing even to some reform advocates because — like the systems they replaced — they rated the vast majority of teachers as effective or better.

(The 74: Test Scores and Teacher Evals: A Complex Controversy Explained)

Still, research has found that new evaluations have likely led to small upticks in the numbers of teachers deemed less than effective.

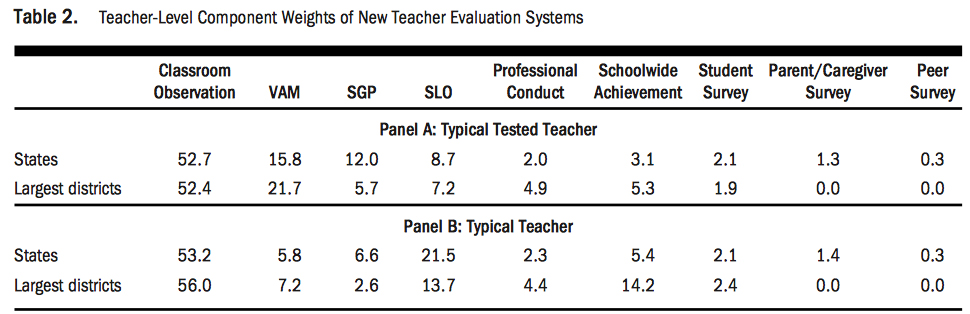

Although much of the pushback has focused on testing, under these systems, the majority of teacher evaluations are based on classroom observations.

This Chicago study — along with evidence from Washington, D.C. — provides some reason for optimism about these new systems. For one thing, it shows that even if relatively few teachers get poor marks, new evaluation systems may still lead to increases in the number of struggling teachers who leave the classroom, without hurting overall turnover.

Another recent study from Chicago — this one done based on its relatively new evaluation system, known as REACH, currently in use citywide — found less top-heavy evaluation ratings compared with the previous system.

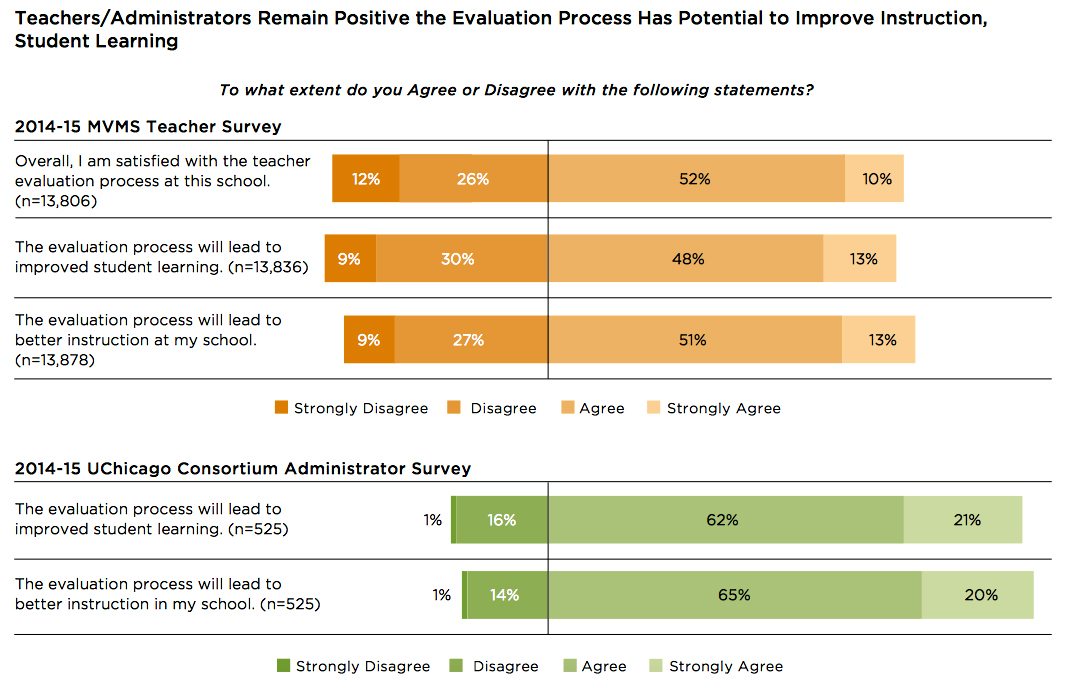

Even more encouraging, Chicago teachers and, especially, school principals gave the system fairly high marks, with majorities saying it “will lead to improved student learning.” Despite anecdotal claims suggesting otherwise, this squares with other studies.

But in one major respect, teachers are not happy with Chicago’s current evaluation system: its use of student test scores. The majority said that assessments were not a fair way to measure their performance.

The older pilot program — which, again, didn’t use test scores at all — suggests that incorporating student growth in evaluations is not necessary to induce less-effective teachers to leave. In fact, some argue that assessment-based evaluation can undermine other aspects of the evaluation process, such as teacher collaboration; others suggest that stringent evaluations may drive prospective teachers away from the classroom. (There’s little firm evidence that either of these claims are true.)

Test-based evaluations, depending on how exactly they’re designed, tend to award more lower ratings than classroom observations — perhaps one reason teachers don’t like them.

The Chicago studies, then, highlight both the benefits and the drawbacks of using observations as the sole evaluation measure. Teachers would likely prefer such a system, which still seems able to weed out a handful of the least-effective teachers (at least the ones without tenure).

On the other hand, test scores seem to provide information distinct from classroom observations, which tend to be biased against teachers with struggling students, according to research from Chicago and elsewhere.

And with the feds no longer pressuring states to adopt certain evaluation schemes, these are exactly the sorts of trade-offs that districts and states must consider, as many once again consider revamping their systems.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)