New Data: Sharp Declines in Community College Enrollment Are Being Driven By Disappearing Male Students

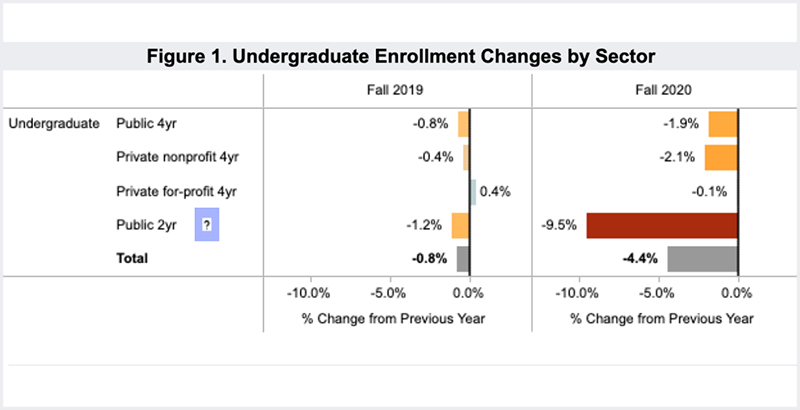

The latest fall college enrollment figures released this month tell a startling story that alarms educators: The sharp declines at community colleges — far larger than at four-year colleges — are due mostly to disappearing male students.

At some community colleges, the losses are minor. At others, however, they are dramatic. At Southwest Tennessee Community College in Memphis, fully half of the Black male students enrolled in the spring of 2020 and still working toward graduation did not enroll this fall. That’s about 830 men who did not return to Southwest, which enrolls 10,227 students, 63 percent of whom are minority.

Where are they? Community college leaders at Southwest and other community colleges have several theories.

Many young men were forced to take jobs to help their families. Others were always academically fragile students prone to put off college or drop out and the pandemic pushed them over the edge. Yet others were derailed by online applications and courses or lacked technology to cope.

One factor often cited: The dramatic spring shutdown of K-12 schools severed students from the college advisers who keep them on a college track. The sharpest drop was among first-time freshmen, a plunge of nearly 19 percent, which is 19 times higher than the pre-pandemic loss rate.

All those observations are undoubtedly valid, but in truth they are more anecdotal than research-based. This cratering of male enrollment at community colleges — just updated in November — is a fresh development; everyone is scrambling to figure it out.

Southwest, for example, mobilized a task force of male faculty and staff to reach out to the 830 men to identify the barriers that caused them to leave and help them re-enroll. “We know they didn’t start school to quit,” said Jacqueline Faulkner, vice president for student affairs at Southwest.

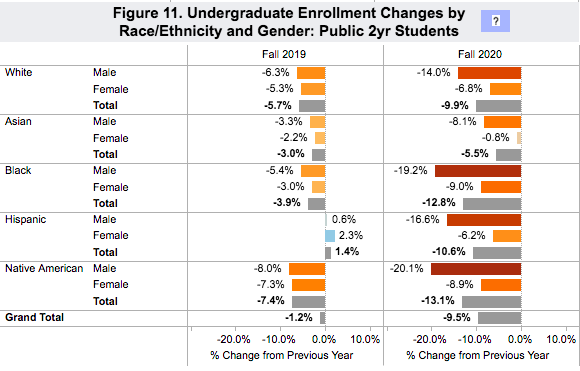

What we do know nationally from the data collected by the National Student Clearinghouse is that Black males make up the biggest portion of these losses, a 19.2 percent enrollment drop from the previous fall, followed by Hispanic males, who experienced a decrease of 16.6 percent. Interestingly, white males aren’t far behind, at 14 percent.

Native American students had the largest drop, at 20 percent, but they make up only .6 percent of enrollments, compared to nearly 10 percent for Black students.

Again, where are they?

Interviews with community college leaders point to the theories cited above. “Most of our students come from Hispanic households, where it is expected that men have to get out there to provide,” said Rick Miranda, vice president for academic affairs at Cerritos College in the Los Angeles area.

That was the case for Cerritos student David Rosales, 21, who was a full-time student there while working part-time as a security guard. When the pandemic hit, his sister lost her job as a waitress and his mother fell ill and had to cut her hours working at a grocery store.

When Rosales was offered full-time work as a guard, he accepted and dropped his classes. “I wanted to make sure we were set, and I couldn’t do full time work and school.” This January, however, he plans to pick up his studies in marketing again.

In Memphis, the technical and financial obstacles appear to be major players. Based on a survey, only 35 percent of Southwest’s students were fully technology-equipped to handle online courses. That led to the college buying and distributing 3,500 laptops. Plus, the college used state and federal pandemic funds to boost the usual $100,000 emergency assistance fund to $500,000, money that went to tuition, food and housing assistance and restoring home utility cutoffs.

It’s possible that the soon-expected vaccine will restore normalcy, prompting males to return to college-and-career tracks. But few college leaders I spoke with expected a substantial return to normalcy.

Nationally, the male enrollment drops appear to signal two separate trends playing out.

The first trend is the scary one, a possible lost generation of males from low-income and working-class families. While Black males make up an outsized portion of that group, it’s important to keep an eye on white males as well, who also disappeared at very high rates.

Before COVID, there was already a severe shortage of jobs for young people with only a high school diploma; the drying up of service sector jobs during the pandemic means far fewer of those jobs. What happens to these young men over time?

To date, the Black Lives Matter movement has focused mostly on policing. This development could shift more attention to a focus on education and jobs.

The second trend is not scary. Several community college leaders say the pandemic has accelerated a trend that was building before the coronavirus crisis, an emphasis on getting specific job training, with or without attaining college credit or a degree.

That appears to be playing out in Louisiana, where there were only slight enrollment losses at South Louisiana Community College in Lafayette, which has strong workforce programs in maritime and computer science, but steep losses at Louisiana Delta Community College in Monroe, where the emphasis is more on earning degree credits, pointed out Monty Sullivan, president of the Louisiana Community & Technical College System.

Sullivan, who serves as board chair of the National Student Clearinghouse, watches these developments at both a state and national level. “There’s a movement of students, who are voting with their feet. They are engaging with colleges, but they are not engaging with the semester system. They don’t have four years to finish a degree. They need a skill set to go and get a paycheck.”

The need to find jobs immediately probably can’t explain all the male enrollment losses. Wouldn’t women have to seek work as well? In part, the gender differences can be explained by the gender makeups of chosen fields. Health care jobs, which draw more women than men, require traditional degrees.

But there’s another player here, one brought up by college leaders, and a factor that proved to be significant 11 years ago when I was researching Why Boys Fail: Saving our Sons from an Educational System That’s Leaving Them Behind. In brief, I discovered a K-12 education system that suddenly veered to ramping up literacy skills in the very early years, a time when boys are far less capable than girls of handling those demands. The idea behind the shift, getting students on an early track to college, was noble, but educators never adjusted to those early-learning gender differences.

Many boys, especially in middle- and upper-income families, adjusted quickly and caught up in literacy skills before the end of elementary school. But many did not, thus concluding that school was “for girls.” That helps explain the twin phenomenon: fewer men than women enroll in college, and fewer men than women are equipped with the intense literacy skills demanded in college, regardless of the major chosen, thus making them more fragile students.

Although all boys were impacted, including white boys from blue-collar families, the worst hit were Black males, who were more likely to face additional headwinds such as dangerous neighborhoods, troubled schools and less-stable families. The pandemic just made all that even worse.

“The pandemic highlighted so many inequities,” said Ivan Harrell II, president of Washington state’s Tacoma Community College. “Traditionally marginalized populations were impacted more by COVID, and they are now figuring how to support their families, which means they have to step away from education for a little while.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)